Nothing Is True, Everything Is Permitted: Wolfgang Voigt, Lawrence English, and Others Ponder the State of Ambient Music

In September of 1978, British singer, musician, artist, and record producer Brian Eno penned a […]

Nothing Is True, Everything Is Permitted: Wolfgang Voigt, Lawrence English, and Others Ponder the State of Ambient Music

In September of 1978, British singer, musician, artist, and record producer Brian Eno penned a […]

In September of 1978, British singer, musician, artist, and record producer Brian Eno penned a short manifesto as an introduction to a new sound he had been exploring. “Over the past three years,” he wrote, “I have become interested in the use of music as ambience, and have come to believe that it is possible to produce material that can be used thus without being in any way compromised.” The compromise he referred to was the proliferation of Muzak, or any of “the products of the various purveyors of canned music” which Eno felt the need to distance himself from. He did this by coining the term “ambient music,” and releasing a series of LPs dedicated to “building up a small but versatile catalogue of environmental music suited to a wide variety of moods and atmospheres.” Ambient 1: Music for Airports launched the four-part collection that same year, and it would establish Eno as the godfather of a subtle and exploratory style of composition that he first touched on with 1975’s Discreet Music.

Since its inception decades ago, ambient music has mutated and splintered into many disparate factions and subgenres; some became timeless standards, while others are now borderline laughable. But through all of these changes, the music has somehow remained resilient, thanks to artists staunchly dedicated to exploring the possibilities loosely outlined by Eno’s manifesto. Matt Carlson, a member of Thrill Jockey-signed Portland duo Golden Retriever, finds that the amorphous definition of the sound gives it nearly limitless applications. “I think I’m drawn towards the ambient because of its openness: its flexibility, adaptability, and malleability,” he explains. “It can be almost anything. It can incorporate quite complex musical ideas without alienating or annoying the listener, and it allows for unconventional ways of working with sound and form without making verboten more traditionally musical—and to me, very satisfying—expressions of mood, melody, and feeling.”

photo by Sarah Meadows

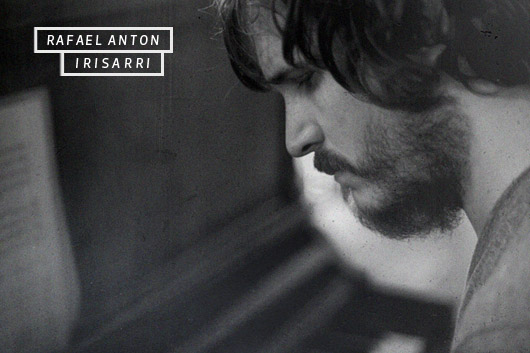

Asking a selection of both established and up-and-coming ambient artists about their music yields fascinating results, insomuch that it’s a bit of a shock when people working in close stylistic quarters have such wildly different reference points and intentions. LA-based producer Deru describes his understanding of the genre in an almost sentimental way, saying, “Ambient music, at it’s best, has a way of getting under your skin and tugging on emotions and feelings that are subtle and out of focus.” Others are far more clinical and academic in their approach; Australian artist and Room 40 label boss Lawrence English posits that, “Ambient music, in many ways, is the post-modern condition in effect,” while John Elliott, former Emeralds synth explorer and curator of Spectrum Spools, finds value in the inherent ambiguity of the genre. “Some of the most striking and enduring art sends no message and implies nothing. It doesn’t tell you anything one or way or another,” begins Elliott. “When artists like Neel, Kyle Bobby Dunn, or Robert Turman make these compelling works which indicate this philosophy is in play, the most rewarding aspect of listening to them is the different interpretations I can draw based on both my own emotional and objective reactions to the work.” In contrast, Rafael Anton Irisarri (a.k.a. The Sight Below) considers the music’s history and endurance to be its strongest qualities. “Compare, for example, Brian Eno’s Discreet Music to Virgins by Tim Hecker,” he says. “[They are] miles apart sound-wise, yet it all fits in the same ecosystem. Part of what makes ambient music so interesting to me is its timeless quality.” San Francisco-based producer Christopher Willits is even more holistic in his viewpoint, and offers what is perhaps the underlying truth to all of these statements when he says, “[Ambient] is such a wide description and seems to keep getting wider. I think it’s incredibly dynamic, so dynamic that we can’t even define what it is.”

photo by Itchy Eyes

In the grey area of Willits’ idea, though, there are indeed some largely unspoken, cardinal rules that define in general terms what ambient music is, and more importantly, what it isn’t. Beatless compositions have long been the genre’s hallmark, if only because a lack of discernible rhythm helps nestle the listener into a more spacious and contemplative zone, but even this particular ambient signifier seems to have become increasingly unnecessary as of late. Kompakt co-founder Wolfgang Voigt, the man behind seminal ambient project Gas (among countless other monikers), welcomes the possibilities into the genre. “From my own experience,” he starts, “I can say a very calm and soft bass drum, marching through a wonderful ambient sound-landscape, will always work and fit, if someone knows how to handle it. For me, ambient works with and without beat.” A similar philosophy has been adopted by burgeoning DIY labels like Astro:Dynamics, Opal Tapes, and NNA Tapes—outposts which curate strains of experimental noise, drone, and synth music with a taste for submerged house and techno loops. Releases from 1991, Basic House, PHORK, Le Révélateur, Best Available Technology, Nenado, and Ahnnu all subvert the canon of ambient music by introducing distinct rhythmic qualities and garish sounds into the kinds of thick, textural atmospheres we’ve come to expect from the genre.

Matt Carlson—who, incidentally, has released solo work and a Golden Retriever cassette with NNA Tapes—breaks down these relationships to their core: “Ambient was supposed to be rewarding if you chose to make it your primary focus, but it wouldn’t demand this from you… Now think about this idea in relation to a record like Manuel Gottsching’s E2-E4, which came out in 1984 and used highly repetitive electronic beats and synth patterns to create a music that, if you sit down and do nothing but just listen to it, is a hypnotic and rich musical experience. But it also works perfectly well if you just have it going while you’re making dinner, and it’s not necessarily diminished by being listened to in this way. So having beats or not really isn’t a determinative factor in a music’s relationship to the idea of ambient, it’s more about how the beats are used and the way the music interfaces with your attention.”

Another NNA Tapes and Opal Tapes affiliate, Wanda Group (a.k.a. Louis Johnstone) is a prolific UK producer working on the far-out fringes of ambient. His hybridized, nothing-is-sacred approach to noise and atmosphere relies heavily on personal field recordings, which are then chopped, mangled, and woven into often lengthy compositions of barely there melody and unhinged rhythmic gestures. Interviewing Wanda Group over email isn’t at all unlike listening to his uncompromising, experimental music. “IT’S REALLY HARD TO TALK ABOUT AMBIENT MUSIC AS I THINK IT’S SUCH A WEIRD THING,” goes his typically all-caps response. “IT’S JUST SPACE, ISN’T IT? LIKE A ROOM WITH NOBODY IN IT. THEN SOMEONE RECORDS THAT. THEN SOMEONE ENTERS THE ROOM AND RECORDS IT WITH A PERSON IN THE ROOM. I REALLY HAVE NO CLUE ABOUT ANY OF IT. I TRY TO UNDERSTAND IT, BUT IT’S JUST THERE AND IT WILL ALWAYS BE THERE. NOT LIKE THE ROOM, THOUGH. THE ROOM COULD STAND FOR THOUSANDS OF YEARS OR COULD BE BLOWN UP IN ABOUT TEN MINUTES.” And whether he realizes it or not, Johnstone touches on a real truth about the essence of contemporary ambient music: It is both ephemeral and continuous by nature, able to communicate the delicate minutiae of a fleeting moment as well as it can inhabit the entirety of a space in virtual perpetuity. Lawrence English echoes Wanda Group’s impromptu reasoning when he says, “I think what makes ambient music interesting and in fact compelling for those really interested in listening is that, ideally, it creates a kind of rupture in time. Instead of music that progresses through a series of set clocks or rhythms, what ambient music does best, I feel, is to create a space in which time is fluid and unsettled.”

photo by Philistine DSGN

“I would say listening to something and not knowing how to describe it is the best thing ever,” notes Editions Mego boss Peter Rehberg. Though not a strictly ambient label, Editions Mego—along with its Spectrum Spools imprint—has championed some of the most challenging electronic sounds in recent memory, many of which swim within the continuum of beatless and/or freeform music. “When we started Editions Mego 20 years ago,” Rehberg continues, “one of the few concepts we had was to do a label that was non-generic. Whether we achieved that or not is not for me to say, but it was quite tiring to see records, artists, labels being pounded into very narrow genres by media and promoters to fit their own agendas. We always fought that. Might be a reason the label still exists.” The problem of unexciting, pro-forma ambient music is also confronted by Jakub Alexander, who—in addition to producing under the name Heathered Pearls—does A&R for Ghostly International and runs the Moodgadget label. He illustrates the point: “A lot of people send me ambient music who are just starting, and it bums me out. It’s easy to just find pretty sounds, and I don’t know every single synth pad or sound that comes with Ableton, which makes me feel like sometimes I’m being tricked. This guy is probably just [using] default sounds, and I’m like, ‘Yeah, this is amazing!’ [laughs]”

Innovation within electronic music, ambient included, has always been closely correlated with advances in technology. At the same time, while evolving technologies undoubtedly impact the music-making process, it’s ultimately up to individual artists to determine exactly how much their end product will be influenced by the tools at their disposal. Wolfgang Voigt recounts how he has matured his production approach over the years, saying, “In the ’90s, my ambient works were more concrete and based on clearly defined concepts and references. These days, I’m much more free and very much more abstract. My main style these days is: I take some basic material and play around with it, based on knowledge and control, while always trying to provoke unexpected accidents—to lose control.”

Longtime synth specialist M. Geddes Gengras sees things differently; as ambient music continues to grow in popularity and reach new ears, he hopes to hear “more attention to composition, timbre, and fidelity,” and his latest LP for Leaving Records finds him putting those ideas to good practice. “Part of my aim with my more ambient works is to create a single-stream experience that can be combined with other stimuli,” Gengras explains, “whether it’s driving a car or falling asleep—music as furniture or domestic tool.” In that sense, a slow-drifting and astral record like Ishi falls squarely inside the parameters first outlined by Eno in ’78, and the analog, modular synths it was written and recorded with don’t sound all that distant from the same era either. Given the unexpectedly favorable press Gengras’ three-song, 35-minute Ishi received from non-electronic, non-niche outlets when it was released in late June, it would seem that explicit innovation isn’t the only key to ambient music reaching a larger audience.

photo by Tim Navis

Though it couldn’t rightly be deemed a trend just yet, a small number of ambient producers have set themselves apart from their growing crowd of peers by releasing dedicated audio-visual albums. Among the current few are Deru and Christopher Willits. The former’s 1979 LP for Friends of Friends arrived in mid-June as a typical digital/vinyl release, though a deluxe, limited-edition version was also made available in a bespoke projector (called The Obverse Box) pre-loaded with Deru’s music and a series of short films by San Francisco visual artist EFFIXX. Willits, on the other hand, will unveil his latest album, OPENING, this September via Ghostly. After gradually disseminating the record’s early singles as music streams and visual works, all seven of OPENING‘s scenes will be featured in a 45-minute film that presents the artist’s full A/V experience as it was intended.

photo by Scott Hansen

“I think that extending the music to as many senses as possible helps draw people in,” says Deru. “Ambient music really benefits when people can have an experience with it. It benefits from a quiet setting, a place where you can listen and go inward.” Willits seems to have almost identical intentions when he describes OPENING: “In my own work, I use images to ground the music and create the space I intend, one where people can open up, chill, and recharge a bit.” This marriage of sound and image may seem like a natural evolution, but for the ambient community at large, it’s not something that can be wholeheartedly agreed upon. Wolfgang Voigt, for instance, seems purely interested in the power of sound. “For me,” starts the German artist, “ambient first of all is listening music, which means: close your eyes.” Along the same lines, musician and Substrata festival curator Rafael Anton Irasarri tells an interesting story from when he used to help organize Seattle’s Decibel Festival. “Many years ago,” he says, “I had the chance to put together a concert by Harold Budd for Decibel Festival in Seattle. I had hooked up a video artist to work on visuals for Harold’s performance, but he was very much against this idea. He didn’t want to have any particular images associated with the pieces he was playing on the piano. I thought that was a very interesting viewpoint—he didn’t write the music with a specific image in mind and wanted to leave that to the listener to interpret in their own way.” And perhaps that’s the crux of the issue: In the end, the question of adding a visual element boils down to whether or not an ambient artist deems it necessary for the nuances and intangibilities of their work to be illustrated so definitively.

Still, regardless of any given producer’s take on contemporary genre expectations or adherence to the guidelines put forth by Brian Eno’s 1978 manifesto, the truth of the matter is that ambient music is currently thriving. Contemporary classics like William Basinki’s The Disintegration Loops, Tim Hecker’s Harmony in Ultraviolet, and Grouper’s Dragging a Dead Deer Up a Hill have long been revered in their own circles, but these artists are now reaching levels of visibility that would’ve previously seemed impossible. Each new Oneohtrix Point Never record is a highly anticipated event, it’s a notable happening whenever Grouper’s Liz Harris emerges from obscurity to perform her ghostly songs, and the return of seminal producers like Fennesz or Gas is an immediate cause célèbre. Even record labels previously uninterested in ambient music are taking steps to explore the genre. James Friedman’s NYC-based Throne of Blood label launched its Moon Rock compilation series at the start of 2014, featuring original beatless productions from Simian Mobile Disco, Steve Moore, Juju & Jordash, Naum Gabo, Pittsburgh Track Authority, and many others. “As the submissions began coming in,” Friedman explains, “I realized that there was a lot of enthusiasm among the artists I know and some incredible interpretations of just what the term ‘ambient’ encompasses. What I had asked for was loose, circular, intensely druggy, synth-heavy drones and ambient with a heavier debt to stuff like Tim Blake’s Crystal Machine than to Pop Ambient. What came back was far more eclectic, and ultimately exciting, than that.” Moon Rock Volume 1 has been so well-received that at least two more installments are already in the works, with the second compilation arriving imminently.

It would seem unanimous, in both the ambient community’s esoteric corners and its largest arenas, that the reach of these musical ideas continues to spread while new artists appear constantly. John Elliott cites newcomer Klara Lewis as someone who “made me feel like I was hearing something new and fresh,” and Irasarri speaks of being drawn into the “lovely textured guitars” of a Frank Ocean performance, finding a genuine commonality between that music and his own. The apparently limitless possibilities of ambient music are at the core of its expansion, which Lawrence English once again wraps up neatly with a burst of his brilliance: “Ambient work tends to be unresolved and therefore free in some way. The rules don’t really seem to be fixed, as Williams S. Burroughs reminded us, ‘Nothing is true, everything is permitted.'”