Polyrhythms and Afro-futurism: 10 Things You Need to Know About Afrikan Sciences

Below the basements and warehouses of the house-music underground lies a subterranean domain so deep […]

Polyrhythms and Afro-futurism: 10 Things You Need to Know About Afrikan Sciences

Below the basements and warehouses of the house-music underground lies a subterranean domain so deep […]

Below the basements and warehouses of the house-music underground lies a subterranean domain so deep that it’s almost completely off the map. These are the spaces and dimensions that Oakland’s Afrikan Sciences (a.k.a. Eric Porter Douglass) explores in his increasingly free-form music, which finds a unique place between the leftfield rhythms of Flying Lotus and the spaced-out, post-techno soul of Theo Parrish. His latest album, Theta Wave Brain Sync, was released late last month. Still, we felt like Afrikan Sciences was someone who merited closer inspection, so we’ve put together a list of 10 things everyone should know about this truly avant-garde Bay Area producer.

Afrikan Sciences ‘Theta Wave Brain Sync’

He started out as a hip-hop producer.

Though Afrikan Sciences is the first project Douglass unveiled publicly, he has been experimenting along similar lines since he first discovered belt-drive turntables and the record button on his cassette deck in the ’80s. “I was the kid in the dorm room with the turntables and primitive recording equipment,” he says. “My collective of collaborators recorded volumes of tapes, mostly free-form improv interlaced with freestyled rhymes and experimental production techniques, like Frank Zappa meets Charles Mingus meets Marley Marl.”

He’s been into dance music for a long time.

Always a DJ, Douglass is quick to point out that there has always been a connection between hip-hop and dance music. “Ever since the ‘Planet Rock’ era, there’s always been an intersection where you had uptempo hip-hop and mid-tempo club music,” he notes. Douglass also cites the influence of New York City radio stations like KISS FM in the ’90s, where he remembers, “you had guys like Bobby Konders rocking next to Kool DJ Red Alert or Frankie Knuckles.” However, he began producing electronic dance music in the late ’90s. “I grew out of love with the climate of hip-hop in that time period, plus I was taking inspiration from all these incredible movements going on in dance and electronic music.”

The majority of his material has been released on Aybee’s Oakland-centric Deepblak imprint.

Started in Oakland by Aybee, Deepblak is one of the major progressive forces behind the city’s deep-house output. Throughout its decade-long run, the label has remained a fixture in the global underground, releasing increasingly experimental music that’s cosmically oriented in the way it challenges conventional melodic and rhythmic structures. Douglass’ music has been integral in the imprint’s development; he’s the “rhythm czar” and has been involved with the Deepblak camp since he met Aybee. Interestingly enough, the two first connected “through a forum of some sort, probably a 4hero message board.”

He’s a fan of science fiction.

“All praises due to the writer Octavia Butler,” says Douglass. Much like the rest of the Deepblak crew, science fiction plays a role in the sonic fiction of Afrikan Sciences. Still, beyond the titles and the implied Afro-futurism of his alias, there’s a subtler influence in the music itself, though not necessarily in the way one might expect. “[I love] the mystery and tension found in the incidental music found in sci-fi: Star Trek, ’70s-era Tom Baker Dr. Who, Dune—that stuff factors big,” he explains. At the same time, Douglass is cautious about going overboard with the overt sci-fi references in his work. “I try not to be blatant about it, I find that can come off a bit cheesy.”

He collaborates with Aybee.

Douglass doesn’t collaborate a lot outside of the Deepblak camp, but his work with Aybee has been particularly memorable. The Nibiru Projekt fused the two producer’s styles together, mixing Douglass’ advanced rhythms with Aybee’s more melodically ambient leanings. The first song on that record, “Ordinance,” directly references The Jungle Brothers’ classic hip-hop cut “Acknowledge Your Own History,” which injects the track with an Afro-centric dimension that seems vital at a time when dance music has largely been stripped of its political potency.

It’s all about the polyrhythms.

Since he first began recording as Afrikan Sciences, Douglass’ music has been characterized by rhythmic complexity. Across his discography, his tracks tend to drift away from conventional percussive arrangements. Douglass prefers hand-crafted grooves, with natural swing pushing his drums into uncharted territory. “Polyrhythms are where the magic is conjured. Odd versus even, dynamics and accents, it’s all language,” he says. On occasion, he even layers conflicting rhythms on top of one another to create more complicated patterns.

He’s not afraid to use three turntables.

Though not a part of his live set-up, Douglass utilizes a three turntable set-up in his studio. “I suppose it directly connects to my love of sound collages,” he says, “and layering for the effect of creating a conversation between the music by introducing various elements together.”

He’s a talented jazz bassist.

The sound of Douglass’ short-scale fretless bass figures highly in his music, with slippery jazz playing augmenting his use of avant-garde rhythms. “I am a self-taught bass player and have dabbled with the instrument, off and on, since the late ’90s,” he explains. But despite his jazz leanings, Douglass has never really played in combos. “I’ve kicked around in roots-reggae bands; my involvement in jazz combos has been more as a live dubologist, capturing sounds and atmosphere from other instruments to add another element to [the] music.”

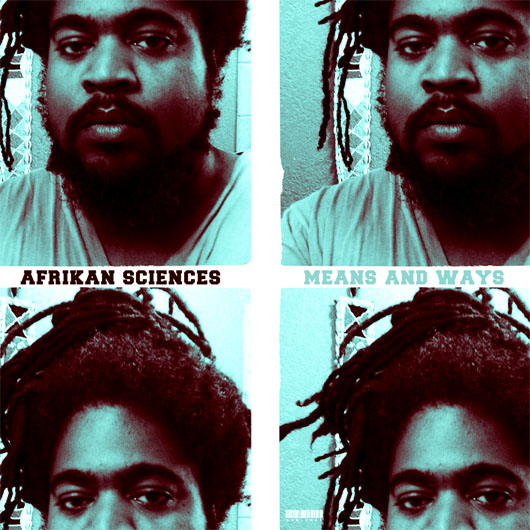

Afrikan Sciences ‘Means & Ways’

Means & Ways, his debut LP, was really good.

On it, he tied together a number of loose ends, making something totally alien in the process. In practical terms, that saw Douglass going from the galactic excursions and twirling arpeggios of “Spirals” to the more Earth-bound, yet still mind-expanding, jazz-combo exercises of “A-Tonk.” Somewhere in between lies an aesthetic influenced by Afro-futurism that’s refreshing in its earnest devotion to breaking with the conventional sonic norms of dance music.

Theta Wave Brain Sync is a true sophomore release.

Picking up where Means & Ways left off, the LP discards some of its predecessor’s more conventional jazz leanings in favor of an altogether more cosmic approach. For the new record, Douglass is drawing cues from the psychedelia of ’70s fusion, utilizing its ethos to explore, in the words of the album’s press release, an “expansive rhythmic dialect [that] points us inward to a sonic palette free of grids. That special place where numbers and counting are rendered meaningless, leaving nothing left for the listener but the groove.” The title refers to a way of sonically inducing altered states of consciousness that was developed in the 1960s. “I’ve researched it and find it fascinating,” Douglass says. “The relationship between specific frequencies, creativity, and the subconscious. The music on this new album I feel ties into that through the imagery it provokes through its layers and textures, kind of like a waking dream.”