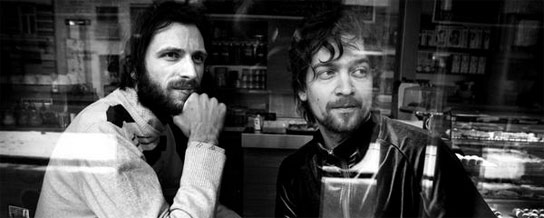

Q & A: Prins Thomas

Disco is everywhere again. From Labelle and Donna Summer getting their senior tour on to […]

Q & A: Prins Thomas

Disco is everywhere again. From Labelle and Donna Summer getting their senior tour on to […]

Disco is everywhere again. From Labelle and Donna Summer getting their senior tour on to Hercules & Love Affair moping and muddling through their West End-inspired sets, the genre America loved to hate has finally taken its seat in American music’s family portrait, nestled between funk, rock, and R&B.

With these overdue developments in mind, it’s fitting that the year’s best disco record barely sounds like disco at all. Lindstrøm and Prins Thomas‘ II, the sequel to their self-titled debut released in 2005, is a mesmeric, constantly mutating Balearic odyssey through prog rock, ’70s R&B, and possessed psychedelia. Where Lindstrøm & Prins Thomas strained against its dance music aspirations, II is a head trip designed to plant you into a beanbag chair.

Though the duo doesn’t have any plans to tour their newest creation, they continue to DJ all over the world. We spoke with “Prins” Thomas Hermansen about II‘s jammy foundations, his unique relationship with Lindstrøm, and playing live.

XLR8R: This album feels much more relaxed and organic than the last one you two made. The first one seemed to strain for dancefloor functionality.

Prins Thomas: I think [when] we started, before the first album, we were mainly doing stuff for the dancefloor. With the first album, we tried as hard as possible to mold our influences into the shape of a DJ set. This time I don’t think we even thought about it. We just made a record. I keep on saying to Hans-Peter [Lindstrøm]—last time we tried to make an album, this time we made an album.

That’s an interesting way of looking at it.

It’s comforting! [laughs] I keep telling people, we’re not really musicians or anything like that, but in a way, we’re getting closer. [laughs]

This is interesting, though, because I read an interview Hans-Peter gave where he was talking about how there was a hesitancy between the two of you on the first album, but as you just mentioned, you guys managed to “just make” this album. What made you feel like you could try again?

I don’t know. I think we thought, when we did our first collaboration, we felt that what we did was quite different to what we were doing solo. And we weren’t necessarily thinking too much about the result or how people would react or whatever. But then it was received much better and more appreciated than we were expecting. That’s kind of scary, in a way. So we’ve moved even further away from thinking about people’s expectations. So we’re trying to make something that maybe people might not get… but at the same time, I think the music we make together has moved even more naturally than the stuff I do on my own. We have this unwritten rule that none of us can say no. It’s very democratic. If one of us has an idea, and the other doesn’t like it, then we have to wait until we’ve both really tried it. When I’m making my own stuff, or when Hans-Peter’s making his own stuff, you only have yourself to argue with, so you often stop yourself in the process earlier than you might, before you can even take the next step.

Where do you think that trust come from?

I think our egos are getting out of hand! To us, people are going to love it! [laughs] I think it’s the result of, every time we do something that’s a bit strange, or weird, or it doesn’t have the feeling you expect from us both, people have been really positive. So in a way, that’s helping us. It’s much more entertaining for us, in the studio, trying to do something new, or going somewhere different from last time.

That sounds like the perfect creative environment. But when did you guys find the time to record II? Was it cobbled together via email, or did you just schedule time in the studio whenever possible.

Well, we share a studio space, which is two separate rooms, or we can open the doors and make it one big one. And we’ve been sharing that space for the last five years.

So you’re used to working, if not together, in the same orbit.

Yeah. He makes the coffee, and I’m [always] just being annoying. Ninety percent of the time we’re working on separate projects, but we still like to take breaks and play records for each other, or just talk bullshit. But I think with this album, some of the ideas started already when we were writing the first album, almost four years ago. And just as with the first album, everything came together very naturally, in fact we were finished with it by the time we were approached by Eskimo. So we weren’t under any pressure to make a same-sounding kind of record. It was just, “Do you want to release it?” and we told them, it would have to be this way the next time, you’ll just have to wait until it’s finished. That’s what happened this time. We only recorded when we felt it was natural, when we had ideas. And we made a double album, at first. There’s another 80 minutes of music that we didn’t put out, because we thought it would be too much [laughs]. I think the eight units we did now, in a way, they move all over the place, but it’s a big seven-course meal, eight-course meal… it came together very naturally….

But because it moves so freely and unpredictably, how did you decide when each song was finished? Are they sort of divided arbitrarily into sections? “Cisco” and “Rothaus” are, in fact, songs, but a track like “Note I Love You + 100” sounds like it could be two or even three. What moved you to combine them the way you did?

I think, with some of them, we just tried putting tracks together, to see if they formed a good track order. And then suddenly, we had them together, and we recorded extra parts to make them fit still better. Actually, one of the last things we did was we overdubbed the whole thing, we played the eight units and added extra parts live, like recording on top of the recording. But some of those songs, like “Note I Love You,” was started with a melody. It was a question of how to lay it down, what instrumentation to use, but most of the tracks were just jamming in the studio. And then, using click tracks, we could play along with synths or bass or whatever, and record new parts on top, and then after a while, it became possible to add hooks, or sometimes while we were jamming, we would find hooks. So this way, what started as a jam and some happy accidents became the basis of the songs. So basically, everything is just jamming.

Do you have any aspirations to take this thing on the road, then? Both because of the music itself and the process by which you made it, that would require something drastically different from a normal DJ set.

We’re actually talking about that at the moment. With the first album, we did one live show, here in Oslo. We got two friends to come in to play the drums and the bass, I played guitar, and Hans-Peter played keyboards. And we played an hour set that was loosely based on the ideas and sounds of the first album. But, just like with recording stuff, we have to find the time. At the moment, these two friends are just waiting for us to say “Let’s do it” and they’ll do it. But we have to find the time, and I don’t think we’re gonna go on any big tours; both of us have families and try to tour as little as possible. I think it’s more about playing select shows, probably more like a concert here and there, maybe a couple of festivals.

So no world-tour-extravaganza.

Nope [laughs].

What was it like to transform the first record into a live show? That must have been quite an unusual thing for you to do. Did it alter your outlook on music-making at all?

No, for me it was… I used to play in bands, ages ago, so for me it was… I was really nervous to play live now. I’m used to playing stuff in the studio. In recording, I’m doing the drums and the bass and the percussion. Hans-Peter’s a really skilled performer, he does this all the time. When he performs, he’s up there with a laptop and a keyboard. So, standing there on the stage, playing guitar with people alongside me, and an audience of people standing there looking at us, I was really nervous. But in the end, everybody, all our friends, said it was a great show. And we had seven hours’ practice beforehand, so it was okay.

Speaking of your busy life, what’s it like running two labels?

I’m trying to put stuff out all the time, that’s why i’m doing it. I’m trying to focus only on the fun stuff, the artistic stuff.

So you must have partners.

Well, with both labels I’ve got one guy doing the design who lives in London. So we communicate via email or phone or meet when I’m in London. And I have my partner and distributor in Germany, which I talk to pretty much every day. They take care of the pressing and distributing. I think so far, since starting both the labels, I’ve never even looked at the numbers of either of them. The whole idea is to put everything back into the label and just keep on rolling. At least now, while it’s possible, I’m making my living from DJing, so if I do remixes or make money from records, it’s always a bonus.

About your remixes and collaborations… they’re all very very long. Is there a strategy or philosophy behind that?

No. It probably comes from all the jamming. You have to let it evolve naturally. But at the same time, I know a lot of people who say, “You could have made this six minutes shorter, and then I would have played the whole thing.” But I think in some instances, this is the beauty of a remix, because a DJ can choose to start playing in the middle of the song, or right at the very end. But this is kind of lost on the digital generation. I think now, most people start playing records from the first bar. They play only records that have a kick on the first beat. They start from the first bar, they play three or four minutes, then they mix out, regardless of what’s going on. But I just do what feels natural to me, and I don’t worry too much about whether people play it. I know loads of people who like it, and that’s good enough for me.

Do you think the attitude difference is generational? Shorter attention spans?

I think there’s a time and place for everything. I use both in clubbing situations, when I play. If you’re mixing really tribal drums and stuff, then short bursts can really energize things, but at the same time I can get a crowd really pleased listening to David Mancuso the whole night. I used to complain about a lot more a few years ago, about how all these younger guys don’t know about the good old times or whatever. But even here in Oslo, things are changing. What basically made the whole club scene happen again was young people coming out to clubs, listening to good music, and being curious. Not just listening to whatever’s cool right now. I meet loads of people, when I travel, DJs who are from that, like, neon, ravey, MP3 kind of scene, and I think that a lot of them, maybe they don’t have a deep relationship with the music they’re playing. They know about some of the stuff, but not all of it. And I think that’s just the way it is now.

What did you listen to growing up?

Everything. I grew up in a good environment for music. Both to be able to go to school and learn different instruments and to buy music from the local store in my hometown and having my parents give me music all the time. Everything from Miles Davis to The Cramps to Ry Cooder. Since I was six years old, I always spent my pocket money on music.

Do you think there are specific artists or experiences that led you to the kind of music you produce now?

I don’t know. One very influential experience was my first hearing DJ Harvey, whenever he came to Oslo for the first time, they were pushing that sound… well, not sound, but all-encompassing disco thing. But I think, I’ve been speaking with Hans-Peter about how we were thinking of doing vocals on the first album, at one point, and then we kind of felt, well, all the music already has so much happening. It’s already so busy, vocals would be over the top. And I think a lot of the spaces felt in instrumental music, more than anything else, for both of us, is what inspires us. When you can let the tracks go somewhere, just by sound… I don’t know. I don’t think our music is mystical or magical, but I think we’ve tried to make it that way. And we’re really happy when people feel that it is [laughs].