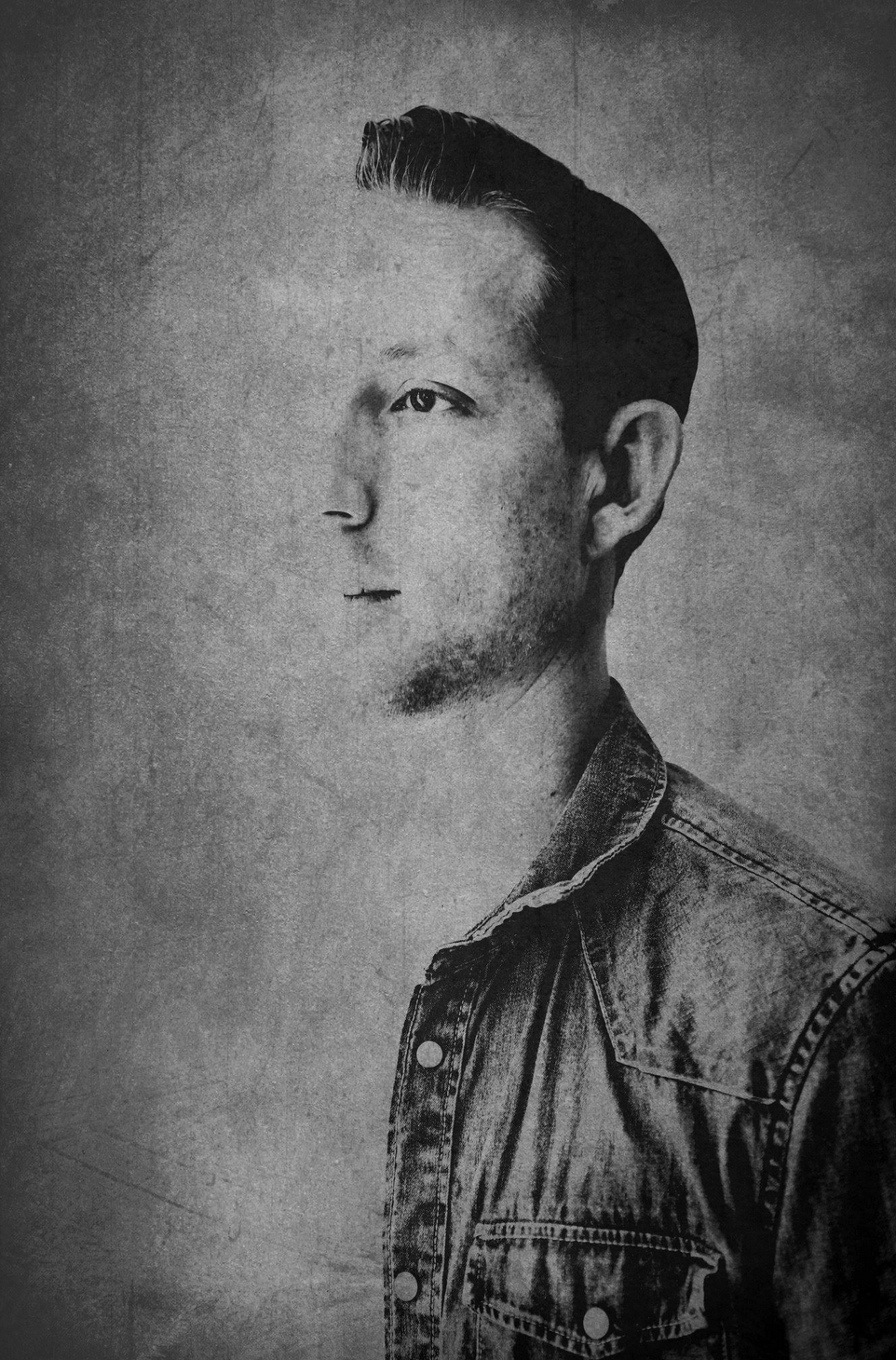

Q&A: Clint Stewart

The Second State artist shares his story.

Q&A: Clint Stewart

The Second State artist shares his story.

Florida, Hawaii, San Francisco and now Berlin: It’s been an interesting ride for Clint Stewart, the surf-loving American DJ-producer known for his work as one of the first core artists on Pan-Pot‘s flowering Second State imprint. However, while many artists use studio work to help fill their touring schedule, Stewart made his name in the DJ booth during a seven year stint on the West Coast of America. It was time that saw him refine his skills with a series of underground parties, becoming a key figure in the area’s techno renaissance.

Production, for Stewart, has always been a secondary endeavor, and something that he has struggled with since the end of Safeword, the internationally acclaimed Mobilee production duo whose “Heavy Burdens High” rerub was featured in Maya Jane Coles‘ Essential Mix and made Rolling Stone’s top 20 mixes of 2013. But EPs are now beginning to flow, notably with the release of last month’s Shelter EP—with more expected to follow early next year.

Over the course of three hours in a Berlin park—with Calvin, his beloved (and indefatigable) Weimaraner dog by his side—Stewart explained the sources of his profound music ambitions, the importance of retaining his artistic integrity, and the role of San Francisco, Second State and the Safeword collaboration in his his development.

So you grew up in Florida—but how did you get here?

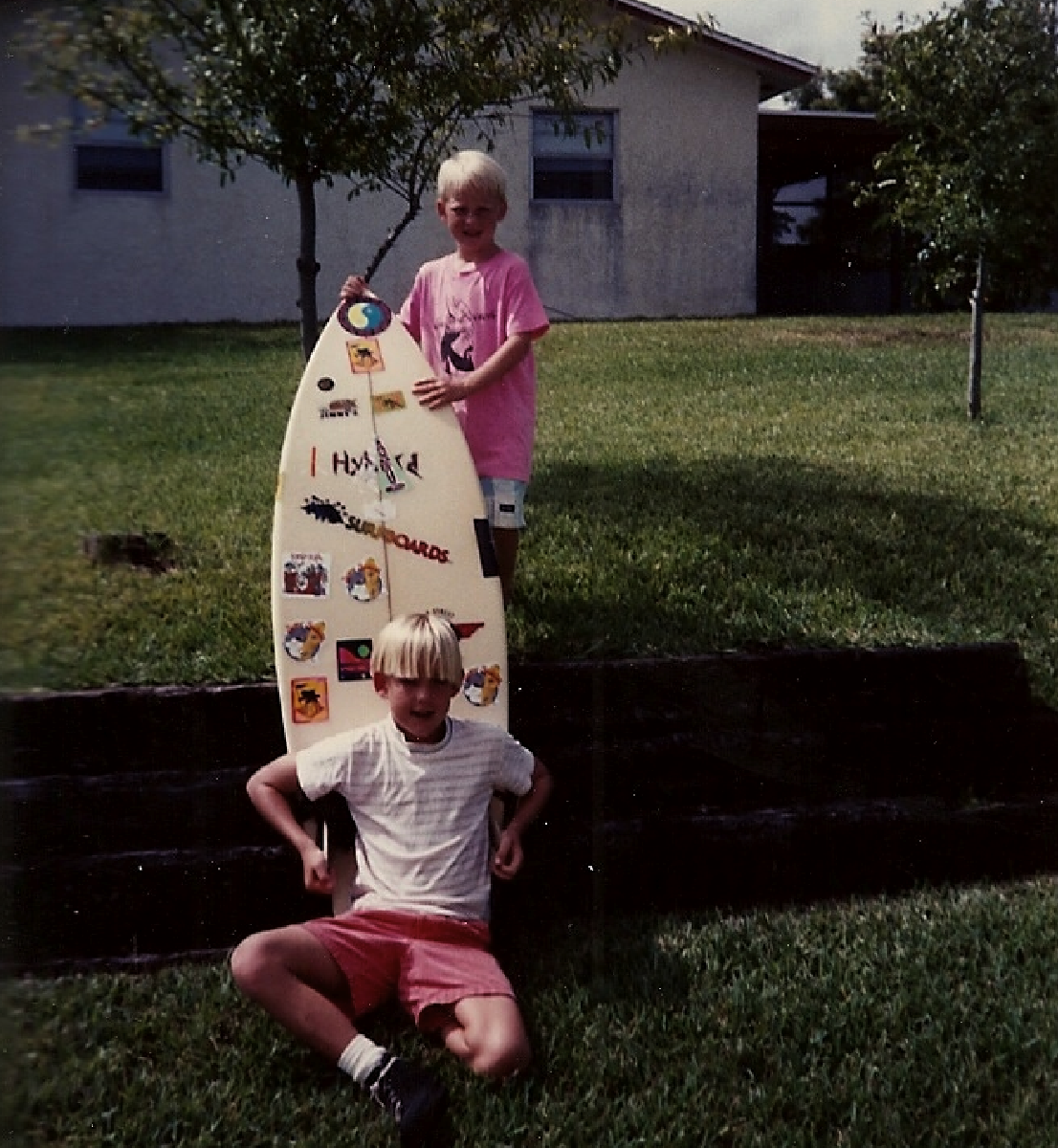

I was born in Jensen Beach, Florida, about two hours north of Miami, and I lived there until I was about 22, when I moved to Hawaii. My childhood was pretty normal—I was just the typical delinquent boy who played a lot of sports and spent lots of time by the ocean. Surfing has always been a part of my life, alongside fishing, diving, and being in the boat—and I think these experiences have gone a long way into making me who I am today.

When did music come into your life?

I’ve always been a huge music junkie, from even when I was just a little kid. I was having regular guitar lessons when I was about eight years old and then I started learning the piano, encouraged by my mom. My parents are both big music lovers—they would be playing classical or blues through the house each morning—and so I grew up around it. I used to go to sleep each night with music playing.

But this wasn’t electronic music?

No. I grew up with surfers and skaters and so when I was really young, about ten or 11, I was into Misfits, Minor Threat or Metallica. I didn’t get into electronic music until I was 18 years old, so actually quite late—and up until I got into it, I completely hated it! I was basing it off a completely ignorant perspective of what electronic was. I thought that everything was techno—even drum and bass, at the time.

“I was never going back to some hole in the wall basement that is covered in sweat with a bunch of angry dudes trying to beat the snot out of each other.”

Why do you think you got hooked on techno?

I went to school in Boca Raton, Florida at a place called Lynn University, which is a private school. I had like a 2.4 GPA but they gave me an academic scholarship because they had to give a certain number out—and I was just really lucky. I went to school with the kids of the CEO of FedEx, whose families owned banks in the Middle East—my mom’s a school teacher and my dad is a contractor, dude! It was there that I met these two identical twins, Karim and Maurice Neme, who were right next door to me in my school and they were the coolest, most interesting dudes ever. They’d always be playing music, like constantly, but I had no idea what it was—it was like the 1999 John Digweed dark, techy sound—and then one day I just got hooked by it. They took me to this party where this music was playing—and that was the switch! There was a sea of beautiful women, everybody was smiling and being really cool to each other. I was never going back to some hole-in-the-wall basement, covered in sweat with a bunch of angry dudes trying to beat the snot out of each other.

“That year or two of discovering new music was so powerful—that feeling you get when you discover so much new music is a feeling I’m not sure I’ll have again.”

That must have inspired a pretty amazing period of discovery.

Yep. From there it was just digging. I came across Matthew Dear’s first work on Ghostly, the first time I heard this really rough, analog, weird, minimal—and that’s what exposed me to Perlon Records and Ricardo Villalobos. That year or two of discovering new music was so powerful—that feeling you get when you discover so much new music is a feeling I’m not sure I’ll ever have again.

Was it quite obsessive?

For sure—and it still is today. I am the type of person where if I get into something then I get obsessed. I don’t get into a lot of things, but when I am then it’s 100 percent. That thing has been music for a long time.

“With social media and things like Youtube today, the wizard’s curtain is not there anymore—everybody can learn to be a DJ—but at that time it was like unicorn shit.”

When did you you first get behind the decks?

After that year in 2000, I transferred to another college—for no other reason than to get closer to to beach. At this stage I knew I liked electronic music and I worked on some nights, and then I met a guy who was selling two Gemini belt-drive turntables for $200—and so I brought them, even though I had absolutely no idea how DJs did anything. With social media and things like YouTube today, the wizard’s curtain is not there anymore—everybody can learn to be a DJ—but at that time it was like unicorn shit.

Did you just teach yourself?

Yep. I just wandered down to a record store and just bought a some records that I thought I liked. I had a radio show at college and I just spent hours working it out—but I started out just playing tracks because I didn’t know how to mix. There were times that I really wanted to quit because I couldn’t get it right—it was just like six months of trainwrecking.

“It was nice to learn the old fashioned way, on shitty turntables. It’s like learning how to ride a bike on a unicycle!”

When did you begin DJing at parties?

I met a guy called Larry Banks who was a pretty integral part of the first wave of European electronic music that came to the States. He showed me a lot of stuff, and helped me get some gigs. I just played opening set after opening set, which actually really develop my skills. It was nice to learn the old fashioned way, on shitty turntables. It’s like learning how to ride a bike on a unicycle!

Were you playing quite a lot at this stage?

As much as I could! After college I moved back down to Palm Beach with my girlfriend, and then I met some guys—including Marc Smith, who I started Safeword with. We started working together, DJing and making music, and we all decided to throw a party on Sunday nights in Miami. It was at this little Cuban place and on the first floor there was a Cuban salsa band—that was like a sardine can, with people queuing to get in—and then upstairs was just us three playing this weird minimal tech stuff. People had no idea what we were doing and looked at us like we were idiots.

Why did you move to Hawaii?

I was only like 22 at the time, and I was super broke—really struggling on about $400 a week that I earned from doing graphic design for a small Boca Raton newspaper. My younger brother was living in Hawaii and earning a ton of money in construction. Dude, so I jumped on a plane over there to work with my brother. I just fucking did it. My whole thing was that I loved music, but realized that I didn’t know the right people and it was a really frustrating endeavor to push music without having any gratification for doing it.

And then how did your work with Auralism Records in San Francisco come about?

Before I left to go to Hawaii, my buddies who I was working with in Miami decided to start a record label—called Auralism Records. I was doing all the design for it, even though I wasn’t properly involved—and then the label moved to San Fransisco.

Is that what took you over there—and eventually made you stay?

Yeah—I would go to San Francisco quite frequently to play some parties and hang out with my buddies. In April of 2007, I was playing the official label launch party in San Francisco at a now-gone but legendary placed called the Compound—and I had never experienced anything like it before. I just decided to stay there to help out with the label and pursue music.

Was it a spur-of-the-moment decision?

It was—there was absolutely no plan to stay in San Francisco. There was only about two days between me thinking about it to calling my brother and asked him to send over my tools. But I’ve always had this spiritual side of me that makes me pursue things now—because it may be the last day.

And then you very quickly enjoyed some success, becoming a regular at undergrounds and warehouses in all corners of the city. Do you see the fact that San Francisco, at the time, was going through something of a techno renaissance as an important factor in your success?

Absolutely. Everything in life comes down to timing, and it was a really unique time when I was there. I was very lucky to have the people around me, all of whom had developed their own connections who then pushed me further. In 2007 you couldn’t find a club in San Francisco besides the EndUp—it was all underground, and I would go out five days a week, to more than one party each night, and there would be over 1,000 people at each one. It changed in 2008 because here was a change in law enforcement and the new sheriff wanted to get rid of these underground parties —but at that time it was one of the best places in the U.S. for techno.

It must have been a pretty amazing scene to be in.

Definitely. Everybody was so young, fresh and hungry—because nobody had really become a big international player at the time. And then you compound that with the San Francisco culture of free love that resonates from the ’60s. It’s essentially a bunch of young hedonistic people making music.

“Those parties definitely helped grease the wheel of moving along—it’s a very social industry. If you’re DJing alone in your bedroom then you’ll never get anywhere.”

Were you making a living from music at the time?

I quit my job in construction a year after moving to San Fransisco because the gigs started to pick up. But to begin with I was living with two mates—Alland Byallo and Jason Short—in the living room on a mattress. Every weekend we would rage and have a big after-party there. Those parties definitely helped grease the wheel of moving along—it’s a very social industry. If you’re DJing alone in your bedroom then you’ll never get anywhere.

How did your residency at 222 Club come about?

Technically I had a residency there because we were doing this party called Lil Brthr, which was an offshoot of one of our other parties. I was a resident then because I was playing there regularly—but eventually it came up for sale at the same time my buddy Emilio was looking for a place. It happened like this: “Dude, you should buy that place,” and he was like: “I have always wanted my own place.” And so he did it—my buddy owned 222. That’s when I really started playing all the time.

Do you reflect back and view those seven years in San Francisco as when you really refined your skill set?

Absolutely. Refined is an understatement. I knew what I wanted but I was exposed to new things, living and breathing music. It played a huge role in developing me into who I am—and that’s why I don’t really correct people when they say I’m from SF, because everybody knows me from San Francisco. That’s where I made my name when it comes to music.

In 2013 you then moved in Berlin. Was this simply to push your music?

Sort of. I had been coming to Berlin for a while for gigs, and even people like Tassilo and Thomas of Pan-Pot were telling me to come. But I never wanted to move to to be successful; I only wanted to make the move when I had established a substantial foundation—and then Berlin would be the next logical step to push it further. It’s stupid to think you’re going to come here and stand out.

And so you felt like you had a platform by this point?

In 2013, yes. But the thing that really triggered it was more personal. I had some things going on with my family—and then when I got home from sorting it out ,my girlfriend broke up with me, just like that. That lit the fire under my ass. At that time I was doing music but I wasn’t 100 percent committed. I needed a fresh start, and then Tassilo and Thomas had offered me the opportunity to really push my music further with their exposure.

How did the move to Berlin tie in with the end of Safeword and the start of Second State?

When I moved to Berlin, I was working with Safeword and wasn’t even thinking about my solo career at the time. Marc, my partner in Safeword, was here too, and Mobilee were about to really push us as their next roster artists. I was staying at Tassilo’s house and one day he told me that Pan-Pot going to head in their own direction and start their own label, Second State—and they wanted to push me as their first artist, but only as a solo act.

How did your relationship with Thomas and Tassilo first come about?

A week after I decided to move to SF, we threw an Auralism party and booked Exercise One and Pan-Pot. I ended up taking care of the guys for the time they were here and we all hit it off. Thomas actually wasn’t there as he was still pretty weary of flying at that tim,e so it was just Tassilo. After the guys left, Tas and I kept in contact and when they came back the next time they stayed at my house for a week.

But couldn’t you have continued with Safeword and as a solo artist?

Thomas and Tassilo’s offer was the kindling—but it’s not the reason we split up. I obviously didn’t want to end Safeword, but at the same time I had to look after myself, and this was a big opportunity to move forward. I really wanted to do both, but I soon realized that wasn’t going to work, and both Marc and I had different directions musically that we wanted to pursue. There was a point where a realized that Safeword was never going to work between us anymore, so I had to focus all of my energies on my solo work.

Is it different producing as a solo artist than in a collaboration?

Yes. That’s been a very difficult transition for me. As s producer, I am hypercritical and so I end up shooting myself in the foot because I won’t put any music out. I throw out over 95 pecent of the things I start. This is obviously easier in a collaboration—and in Safeword we had an identity because we were the guys that created it. It was music that came from a very artistic approach, and we had this cool dynamic where I was the DJ and Marc was more of a musician—so we had this meeting in the middle, which was cool. Going from this to just me has been a challenge.

Is this why your output—just three solo EPs in about 14 months—has been so low?

Yes. I am really trying to battle this hypercritical voice in my own head. I am definitely getting there now but it’s taken some time.

Why do you think you’re so critical of your work?

I think I am still developing my sound, and putting out music is an extension of my soul that people are going to judge.

Do you think your output will now increase, having had some time to adapt?

Definitely. I thought it would take me about six months to adapt to the new situation, but its taken me two years. I’ve learned a lot over that time and I do feel more ready now. Only now am I settling in to knowing what I want and knowing how to get it—both musically and otherwise. 2016 is going to be a big year.

Do you have a vision of where you want to get to, artistically speaking?

I am really happy with where I am now—but I am never going to be satisfied. I’ve done some gnarly jobs in my life, and know how good I have it, but I will never be content with my status. I want to play everything, everywhere and go as hard as possible for as long as I can. I want to release music that changes people’s lives, that has an emotional impact on people, and that is timeless. It’s important to me that I leave a legacy. I want a body of work that people respect and enjoy.

Has an album crossed your mind?

I have been putting a lot of thought into it—and it will come.

You talk about leaving this legacy. Is this something you’re very conscious of?

Definitely. It’s all about quality over quantity with me—I am never going to release more than two or three EPs in a year. Some of the most talented producers I know are never going to get the acclaim they deserve because they spread themselves too thin over too many different labels—so it is a real science to ensure you put out enough so your fans are content but always ensuring that they want more.

Does this impact the labels that you currently work with, or would work with in the future?

Yes. If I were to release on some big name labels, my DJ career could blow up—but do I think it’d be a good idea? I don’t want to jump on the bandwagon just to jump on the bandwagon, and I think this has probably slowed down my success as an artist. I hate the idea of putting out a record to push your DJ schedule and so I am wouldn’t want to do this. I am a DJ, first and foremost. I use other people’s must to tell my story.

So there are labels you wouldn’t put your music out on?

I will never say never, but it has to make sense. If I don’t maintain my integrity as an artist then nothing matters.

“If you take a while to get there then you’ll stay there, but if you come up fast and take shortcuts, then you’ll go down fast too.”

Do you think your profile could be bigger now?

Possibly, but I didn’t take any shortcuts. I did it the right way—the old-school way. There is an infinite amount of ways to be successful. Mine isn’t the only way obviously, but I’m proud of the path I’ve taken. It’s all about the slow-burn: If you take a while to get there then you’ll stay there, but if you come up fast and take shortcuts, then you’ll go down fast too.