Q&A: Trentemøller

Intimate studio conversations with the Danish multi-instrumentalist.

Q&A: Trentemøller

Intimate studio conversations with the Danish multi-instrumentalist.

Dig into Anders Trentemøller’s discography, and you’ll find some of the most cherished electronic music of the past two decades. At its foundation lies a non-conformist attitude and an upbringing centred around two contrasting musical landscapes: rock and electronic.

Growing up in Copenhagen, Denmark, a young Trentemøller first connected with the former of these, and spent the twilight of his adolescence performing in alternative rock bands, inspired by the likes of My Bloody Valentine, Joy Division, and Depeche Mode. It took a trip to London, during which he discovered Massive Attack, Tricky, and Portishead, for him to unearth an affiliation with the latter, at which he point he formed Trigbag, a live house act alongside DJ Tom Von Rosen (a.k.a. DJ T.O.M), formed in 1997. Upon the band’s dissolution after just three years, Trentemøller set up on his own, and, in 2006, following a run of EPs, released The Last Resort, his groundbreaking debut full-length that topped several end-of-year polls. With its memorable melodies and lush sonic soundscapes, the album forms a milestone in contemporary electronica, riding the line between being a collection of songs, each with its own personality, and presenting itself as a single body of work.

This dichotomy, between rock and electronic, has underlined Trentemøller’s 20-year career. In The Last Resort‘s wake, Trentemøller formed his first full live band, complete with Henrik Vibskov on drums, Mikael Simpson on guitar, and visuals from director Karim Ghahwagi. He followed a similar pattern with his next three studio albums, Into The Great Wide Yonder (2010), Lost (2013), and Fixion (2016), all of which came out on his own label, In My Room, and were quickly translated to the live format. He’s now completed multiple world tours, playing nearly 500 shows. “Personally, it’s all about finding a balance between this solitude [of working on electronic music in the studio] and working as a band, and I carefully manage my career so I can enjoy both sides,” he explains.

Trentemøller’s ability to caress the best of rock and electronic into his own inimitable style is felt through all his work, but the equilibrium felt lost somewhat on Fixion, his most recent full-length. Informed, no doubt, by his time on stage, which was becoming ever-more demanding by this point, the album felt like it was written with the live-side in mind; as if Trentemøller had put the cart before the horse, much to the dismay of some of his sternest fans.

In contrast, Obverse, Trentemøller’s new album, is written without the stage in mind at all. Knowing that parenthood would require that he remain at home for the foreseeable future, Trentemøller set about writing what he intended to be an entirely instrumental album, but also one that was not bound by the idea that it would necessarily have to be translated to the live format. Using this liberating notion as a launching point, he took advantage of chasing down every idea, and exploring every tangent—using the studio as a tool in itself, all the while mining familiar themes of light and dark, turbulence and serenity, piercing chill and comforting warmth. “Because I wasn’t thinking of translating it to a band, it feels less band-like,” he explains.

To learn more about the album, and the processes behind Trentemøller’s work at large, XLR8R connected with him in Copenhagen studio, where he sits, rather nervously, in anticipation for his first child and his first album in nearly three years. What follows is a shortened version of this conversation.

Talk to me about Obverse, coming out in September. How are you feeling about it?

Releasing music is always really nerve-wracking, and this even more so because it’s the first new music I’ve shared in nearly three years. These months before the album are always special because it’s when you realize that the music is going to have its own life, on Spotify, vinyl, and wherever else it comes out. It’s been my own little universe for so long, and it’s nice to let it go because I can now begin working on something else. It’s difficult for me to start on new music until the album is actually out; it’s like being in a psychological limbo.

How was the album to write?

It was extremely hard to begin with, because I had seven or eight months of writer’s block around the time I wanted to start, and I didn’t think anything was good enough. After a tour, especially the last one where we had around one hundred shows, it’s always hard for me to feel comfortable again in the studio because I’ve been surrounded by the band a lot. To write albums, I must be really immersed in the sound, and this is a big contrast to being with the band, practicing and touring, so it normally takes me two or three months for me to feel inspired again, to find the headspace. I think this time took a lot longer because I didn’t feel at all satisfied with what I was coming up with. I was really trying hard in the studio, and at one point I thought to myself that I had totally lost it, so I actually stopped and worked on other stuff. It was only then that my inspiration came back, very slowly; day by day, I started going back to the studio, and then the album was completed in nine months.

How much are you thinking about the album’s reception?

I don’t think about that at all when I’m in the working process. If I did then it would simply confuse and distract me too much. When the album is finished, I, of course, hope people “get the music.” I think it’s an album you need to hear several times to really get into; to discover all the details etc., so I hope some will do. I also have my doubts in these Spotify and playlist times. The album format is under pressure and I guess most new listeners will just pick out a single song they immediately like, put it in on a playlist, and that’s it! (Laughs). It’s ok, but I hope people will take their time to listen to the album in its entirety.

Many of the tracks on Obverse feel closer to your earlier work. Why do you think that is?

It’s not easy to say, but it’s perhaps because I knew that I wasn’t going to follow this album with a world tour. I knew I was going to be a father while I was writing the album so I was not going to be able to tour, so I saw it as an opportunity to really do a proper studio album, without having to think about how I would adapt the music to the live stage, with a band. Not only has it been a lonely process, but it gave me some freedom to actually play a little bit more, and to experiment a little bit more, because I didn’t have to consider recreating it using 17 different guitar players on the stage. That would be pretty impossible!

Do you think this is why it feels more electronic, rather than the song-focused works of the last two albums?

Maybe, but I certainly wasn’t conscious of this when I was making the music; it was just because I was using the studio as an instrument. On my previous albums I would record each instrument, synth, drum, guitar, bass, and vocal, and then put the music together in a more traditional way. Basically using the studio to do recording, so each instrument had its part to play in a song and its place in the mix. In contrast, this time around I wanted to see where my studio, with all its effects and possibilities for sound manipulation, could take me if I drastically used and mis-used it. I wanted to process the shit out of a guitar until it sounded like something completely different. And experiment with running the whole mix through different crap tape recorders to get a kind of unearthly sound. I was going crazy with my synthesizers and also using a lot of effects pedals because I have collected so many of them.

There was some criticism of Fixion, because it felt too much like songs rather than electronic music. How much did this impact this move back to the latter?

Not at all. I think it’s important to not go back with your music. I don’t really think about external critique or expectation when I am in the studio because if I did then I would not be able to make any music; it would actually confuse me. It was just the way the album came out, because I used the studio as an instrument. Because I wasn’t thinking of translating it to a band, it feels less band-like.

Was the idea always to produce an album, or did it happen more naturally?

After we had finished touring with Fixion, I had this idea that it could be great to do a one hundred per cent instrumental album, and so I had this basic idea, yes. But, as happens so often with me, it rarely actually follows the path I intend so I quickly ended up adding vocals because I felt some of the songs were really demanding vocals. The album somehow didn’t feel right without them. I then had some tracks with vocals and others without, but they somehow all felt right because I felt they were all in the same sonic universe.

How do you make sure you present something different with each album? Do you set limitations, or a focus, or theme, before you begin the recording process?

It’s actually something I really try not to think about when I am making music. I don’t want to have a framework or this feeling that it has to be something new, or something I’ve done before. It’s much more about the mood that I am in at any moment, and then often something exciting becomes apparent halfway through the process when I find a sound that I like, and that’s what I explore.

For this particular album, knowing that I was not going to translate the album to a band, and the initial thought of doing an instrumental album, led me in a certain direction, and resulted in tracks that are eight or nine minutes long. When I had this focus, I knew I wanted the songs to be a journey in themselves, so it’s not only the album as a whole as a journey. I realized that I wanted the songs to start in one place and end up somewhere completely different.

You come from a rock music background, and the dichotomy with electronic music is something that has followed you throughout your career. Could ever be totally satisfied as an electronic musician?

I would feel limited if I worked only with electronic music, but I don’t think in those terms when I am making music. I am just trying to make something that I feel is quality music and then it ends up like this. Maybe the next album will be totally folk—who knows? It’s more about where the music takes me, and I am always trying to be more open before I start working on an album. I often start, especially with Fixion, completely away from rock and electronic, with my piano, and then I take it to the studio later. This means I do not get distracted by the various different pathways of the studio; I find it helpful to limit myself early in the process.

Why do you think your music ends up sounding like this?

I think it’s because I really love instrumental music, because it’s easier for me to tell a story because there aren’t any lyrics. There will always be this thing in me that loves to explore the soundtrack-ish vibe to the music; but at the same time, I also love pop songs with vocals, and so it’s like these two sides of me are fighting inside, and I always want to do both.

“So often when you listen to electronic music, you hear 8 or 16 bars or loops, but then it repeats itself and you quite often know what will happen for the next two or three minutes. I wanted to transfer the feeling of a band playing, but not the sound, to the way I programme stuff.”

Trentemøller

You said that you don’t plan to tour this album. How do you feel about that?

I’m honestly already looking forward to touring again with my next album; I’m already missing that live feeling. I’ve actually already started on some live sketches and I am excited about presenting them in the live format.

How much are you consciously analyzing your work in the studio?

It’s almost entirely based on intuition, and what feels right. But then again, this album is a little bit different because I really had some visions of my sound, a feeling that I wanted it to have, and I was always aware of that. So often when you listen to electronic music, you hear 8 or 16 bars or loops, but then it repeats itself and you quite often know what will happen for the next two or three minutes. I wanted to transfer the feeling of a band playing, but not the sound, to the way I programme stuff. I was consciously focusing on this throughout the process, so there are a lot of arpeggios and small melodies that would normally be done on the synthesiser, but instead I chose to play them live so they are not quantized or in sync, and so it all feels a little wobbly.

What’s the test for whether you’re going to release a piece of music: how does it have to make you feel?

It’s a good question. What I am normally doing is something that I realized early in the process. If I don’t record it into my computer or on my iPhone, but I can remember it the next day when I come into the studio and I get the same goosebumps, then I know there is something about it. On the other hand, if I have forgotten the chord progression or the melody the next day, then I accept that it’s probably often not that good. For this reason, I try not to take sketches into my studio too early because I don’t want to waste my time, and I find that my brain often works when I’m relaxed or even sleeping, and I’ll make connections between this base melody and basslines or other things that I’ve done. So I try not to record until I’ve really let them settle. On other times, if I am just jamming with my synths and I am recording, then I’ll always wait a day or so, and see if it still does something to me.

How do you protect this initial idea, once you have it?

I have to keep checking myself all the way through the recording process, because it’s so easy to overproduce a track, and kill this intuitive idea. I’ve learned this the hard way, by spending months on one track and then suddenly the whole magical thing about it was completely gone, so I’ve really learned to capture that first chord progression or melody.

It really is a case of whether it connects with you, not anyone else?

Completely. I make music for my own pleasure, and it’s always been this way. It’s extremely hard for me to try to figure out what people like or what a label will think; if I try to do this then I find that the music isn’t interesting for me, and also not for the listener.

How do you retain this purity in your mind, enough to not block out external expectations?

It’s not hard for me actually. I’m so aware of the importance of blocking external expectations out because I know how much harm they eventually can do. If it’s not playful for me, and if I don’t feel curios or challenged, then it’s not worth all the hard work, I think. It’s all about having the focus on what I personally like, what gives me goosebumps. If I can get those magical goosebumps hopefully other people listening to my music will get them too once in a while.

“I just happen to find beauty in the more melancholic feelings, and when I’m feeling this way I find that small melodies pop into my head.”

Trentemøller

Film and visuals have always played a large role in the delivery of your work. Do you use them as a reference point in the creation phase, or do the visual components manifest at a later stage?

I never visualize my music before starting to work on, so the visuals always come after the music is totally finished. Even if I like to have a visual universe around my music, it’s definitely something that I create afterward. My music all depends on my mood, and I think this is often a little melancholic, a little blue, which is funny because I’m generally quite a happy man. I just happen to find beauty in the more melancholic feelings, and when I’m feeling this way I find that small melodies pop into my head. This is very often what triggers a song, but it can be different.

Does this melancholic state stick with you for the course of the writing period?

I think so. It’s funny that you asked because quite often when I am working on my album, especially later in the process, my girlfriend says that I am really annoying because I am completely immersed in the mindstate of my work. I’m always thinking about it, and, as you always do when you’re creating something new, you hit this wall where everything feels boring. It starts off fun but at some point you have to begin climbing the mountain, and then you take a break. Only after some distance can you see what parts really work and what doesn’t, and that’s when you have to kill your darlings. Sometimes it’s necessary to cut off a lot of stuff, and often I’ll try lots of things out and then end up with what I started with, but this feels like how it should be. Only after this period can I return and be completely present in other areas of my life.

Do you think it’s a case of accessing this emotion inside you?

Yes, that’s exactly it. I have quite a good life, I think, but producing happy-go-lucky songs doesn’t interest me. This is why I need solitude and quiet to really go deep inside myself, and this is why, especially at the beginning of the working process, I need to be alone; that brings me a lot of joy. The loneliness is very giving.

Do you still get the same pleasure out of making an album?

Yes, and this time it was even bigger, I think because I had that period of seven of eight months where things weren’t really working for me, and so it was particularly rewarding to find that joy again. Every time I am in the studio, I turn into a kid in a candy store; it’s still really something that can blow me away. I’ll be sitting there for eight hours and will forget to eat, and I think that’s the magic I am always searching for. If you chase it too much then it can be dangerous, so I think you have to trust that the music will come to you. For me, I know that when that breakthrough comes, I’ll begin writing a lot of music very fast, but this is for a limited period, and I have to catch it.

Did you get the same pleasure from producing rock music, in a band?

No, because in band you have to work in a democratic way, and not everyone has the same ideas for where to go. But it’s not about the genre because you do have solo rock artists who are able to source and express this emotion, like Nick Drake. It’s about the process, and I think as a solo artist it’s easier. There are some bands who manage to do it, like Radiohead and Portishead, but I don’t think it’s easy to do album after album. Personally, it’s all about finding a balance between this solitude and working as a band, and I carefully manage my career so I can enjoy both sides.

Do you think electronic music is a better vehicle for your emotion, or can you convey similar emotions through rock?

I need them both, and that’s why I’ve never thought about my music as only electronic or only rock. As the end of the day, all I am trying to do is make the music as I hear it in my head and sometimes that requires synthesisers, and at other times its drums or distorted guitar. It’s not something I think about; they’re both inextricably linked and I need them both equally.

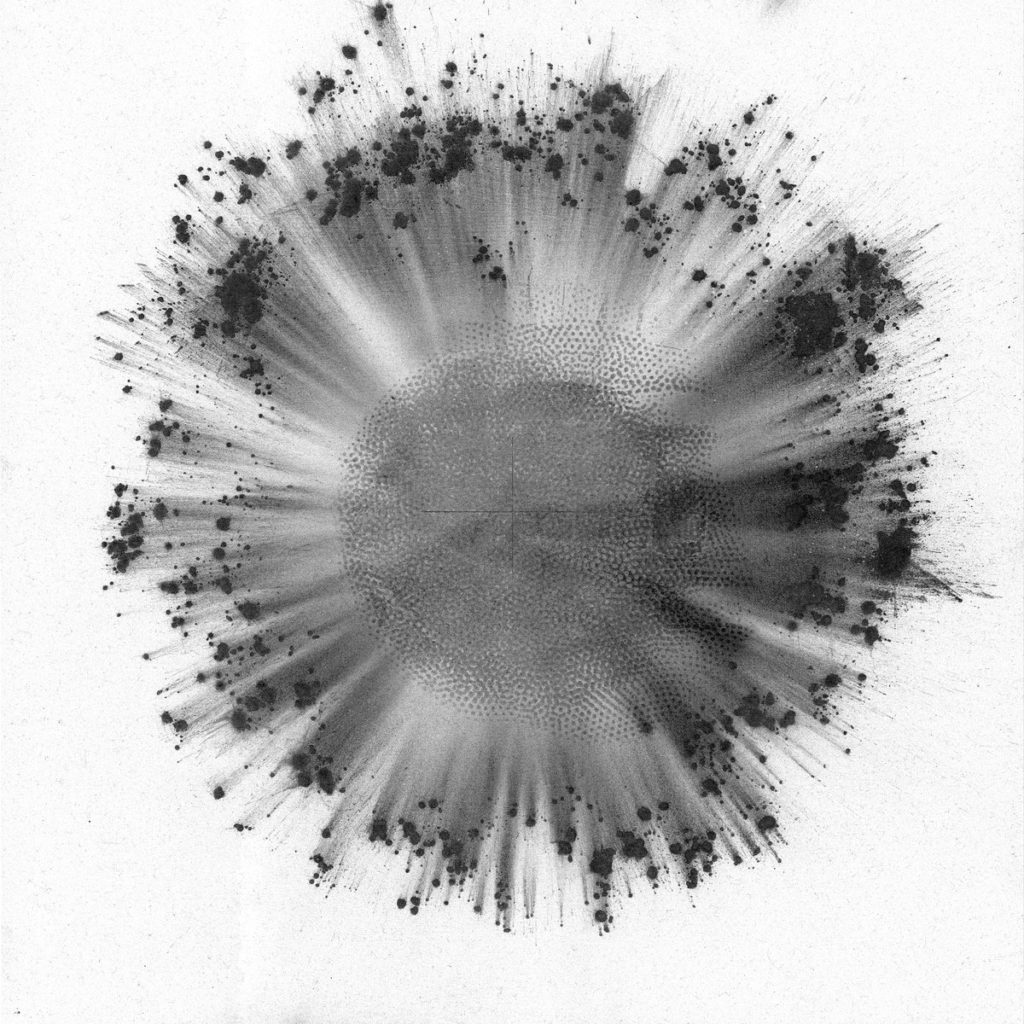

I’m always struck by your album covers—the abstraction and the darkness. How do you go about directing the latest artwork?

I was doing the artwork with a Danish guy, and I had a strong idea of how I wanted it to be. We worked with Jesse Draxler, a guy from Los Angeles actually. I saw some of his stuff, and I was totally amazed by the darkness and the clarity in the work. I really could see a connection between my own music and his work, so I wrote to him on Instagram telling him that I was a huge fan of his, and he told me that he was a huge fan of my music too! We’ve actually not met, but we talk through Instagram and email. For the cover, it’s a piece of his that I bought because I loved it so much; it has an organic feel but it’s also an explosion and some action. He also gave me some other pieces to use on the inside!

What on your feelings on composing for moving picture?

I’ve only ever done it once, and that was for Danish movie many years ago. It’s not something that I’ve been thinking much about because I’ve really been occupied with my own music and then playing live, but I could definitely do it in the future, when I am not touring. I think it’s a little bit like playing in a band, but in a big band, because they have so many people coming in and making decisions on where the music should go. It’s a great challenge, and could actually be frustrating. I do think it can also be limiting on your music if it’s the only thing you do as an artist.

Are you looking for more challenges at the moment, or are you satisfied?

Recording studio albums as I am now is enough of a challenge, certainly. I just want to continue as I am now at present, enjoying this contrast between being completely isolated in my studio for like a year, and then going out and playing music with the band. Perhaps next year we’ll have a whole new band set up, and so there are so many possibilities, but I’m content for now. I also would like at some point to try to translate my music into something more symphonic with an orchestra, but these ideas are just floating around at the moment.

All photos by Jonas Bang.

Obverse is out September 27 via In My Room. Info HERE.