Real Talk: Federico Molinari

The wonderfully gifted Argentinian producer explores his preference for hardware synthesis.

Real Talk: Federico Molinari

The wonderfully gifted Argentinian producer explores his preference for hardware synthesis.

Fans of funky, minimal basslines will already be familiar with Federico Molinari. The much loved Argentinian DJ-producer has been on XLR8R’s radar’s for some time—around the time of his debut EP in 2007, titled Enerverende, in truth—although it was his wonderfully playful “La Vueltica” collaboration with Alexis Cabrera that really captured our hearts.

Between these two releases, and even more recently, lies a deep pool of quality material. Much of this has been shared between labels of friends, including Melisma, Apollonia, and Epilog; although the majority of his cuts have arrived on Oslo, the imprint he co-founded with Nekes as “a way to express their own ideas of electronic music,” and also as a “homebase” for their own productions and those of friends. Within just a few years of its 2007 launch, Oslo had gained widespread both in Europe and further afield for its superb and original releases.

Stylistically speaking, Molinari’s studio work showcases a uniquely groovy take on house music—one that seems to possess a jovial and mischievous innocence and remains as applicable to the peak-time slot as it is the after-hours. Check out “Julio Catorce,”a 12-minute jam with a hypnotizing bassline offered as a free download last year, for a case in point. Now based in Berlin, having moved there from Mannheim in 2013, he has upcoming EPs on Pressure Traxx, Cure Music, and Melliflow—the label founded by Vera and Alexandra.

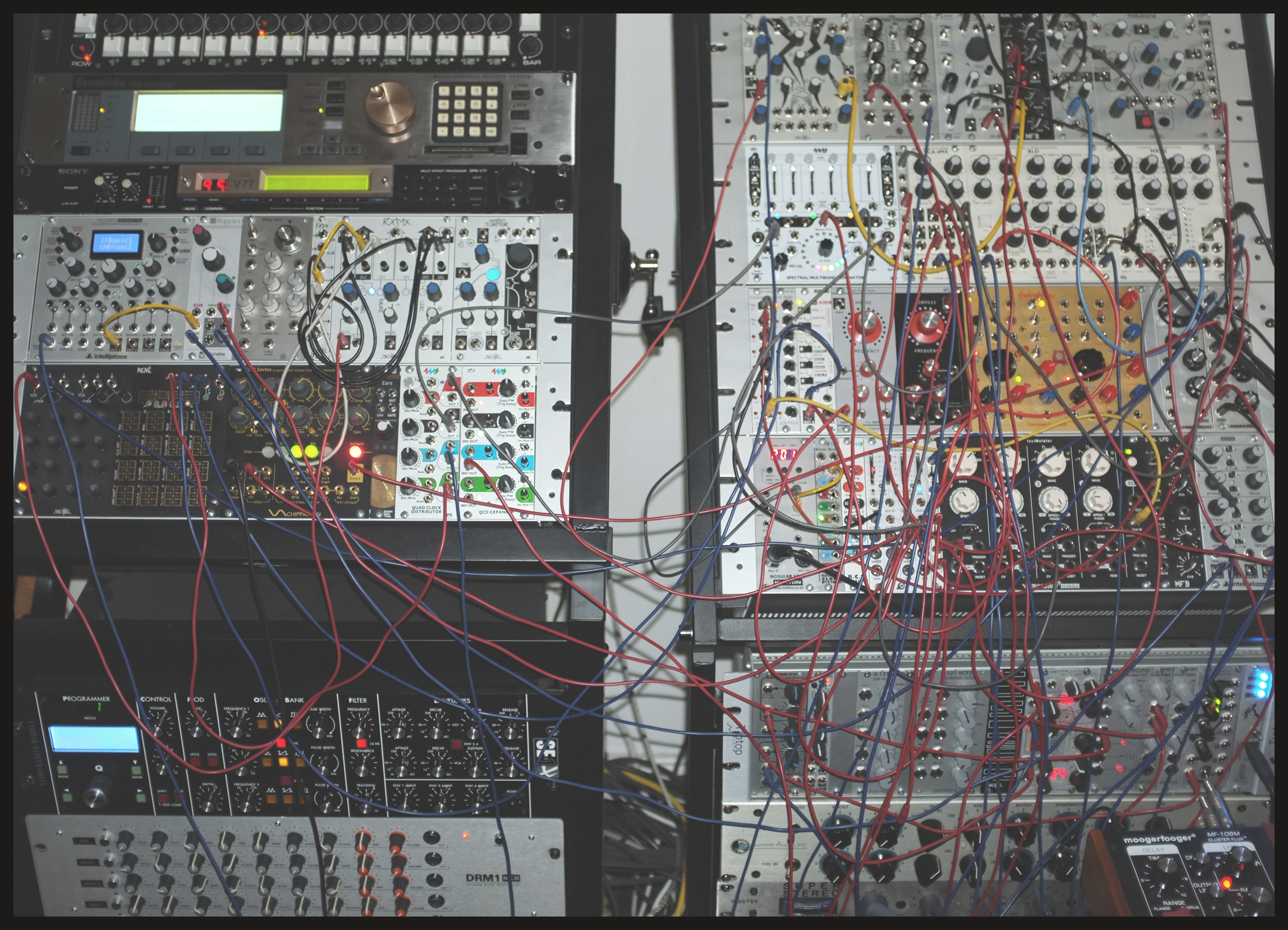

The roots of this style, Molinari explains, lie in his methods: he focuses heavily on hardware methods and modular synthesis, a preference that stems from his early training as a bass guitarist long before electronic music grabbed his attention. “When I switched to this [hardware-heavy] method, my productivity increased significantly,” he continues. “[Before then] I didn’t have the feeling that I was making music with an instrument or even using something close to one.” To learn more about these processes and the specific motivations behind them, XLR8R visited Molinari in his beautiful Berlin studio, situated in the spare room of his Kreuzberg apartment, where he was happy to explain the following.

We’re living in an anarchic decade when it comes to choosing a setup for our studios.

The possibilities that different technologies have to offer are countless and diverse, not to mention the debate on what’s more convenient to use—which is endless. Buying a drum machine, a synth or a mixing desk two decades ago was considerably more expensive than it is today. The new era of virtual instruments changed the game by introducing a much more accessible line of instruments that, while being much cheaper than the real ones, are usually very well designed and deliver excellent results. Because of this, many major companies like Roland or Korg are now focused on producing low-cost hardware so we can now buy synths or even some modules to start building a modular just for a couple of hundred euros.

But who do we trust when it’s time to decide which machine or work method to use? Who should we listen to? If we explore and create music within the plug-in universe, everything seems to be easier given that the routing issues disappear and the costs are significantly lower—if not zero in many cases. However, from my standpoint, the sound quality and workflow radically change when we use machines. But is the result better? For me, yes, there is absolutely no comparison when it comes to hardware versus software: hardware works infinitely better. I have three reasons for this: workflow, character, and sound quality.

Firstly, dynamics—or the workflow. There are several decisive factors when choosing which equipment to use in the studio—when opting to buy a drum machine, a tube equalizer or when using NI Reaktor instead of building a modular synth. Price is definitely one of the main ones—if not the main one—but we also have to consider the practicality and/or dynamics of work that different setups allow us. The method you intend to implement when making music is very important when it comes to defining your setup. In my case, I like having all my machines playing at the same time and recording them all together while modulating different parameters on the fly, with the help of LFOs, of course. When I switched to this method, my productivity increased significantly—not to mention that jamming really feels like making music and it’s much more entertaining than sitting down in front of a computer drawing bars with a mouse. This live recording technique is practically impossible, at least to me, without using hardware.

As for character: today, we can find pretty much everything we have in the analog world in the form of high-quality software, but one of the central points regarding the importance of hardware machines is the use and appreciation of these as real instruments—as if we’re talking about a guitar or a drum set. In general, machines have their own character, and their own limitations too, when it comes to sound and the touch/feel, which is very particular to each brand. It’s the same as when you compare an Ibanez electric bass guitar with a Fender Jazz Bass, just to give you an example.

“…when I began producing with computers, I could never really feel comfortable with that method. I didn’t have the feeling that I was making music with an instrument or even using something close to one.”

I started learning different musical instruments at an early age until I decided that bass guitar was my thing, and I played it for many years. That gave me the habit of always using real instruments when making music. Later on, when I began producing with computers, I could never really feel comfortable with that method. I didn’t have the feeling that I was making music with an instrument or even using something close to one, even though computers are instruments but with different qualities. It took me many years to discover which tools and machines I needed in order to express myself in the best possible way, which is vital to any producer, and after that, I remember thinking of all the years I spent working with the wrong tools, almost as if I had wasted all that time.

My first bass synth was a clone of the legendary Roland TB-303. From the first day I used it, basslines stopped being a constant search and a hassle, to become an easy and effective part of the process. Later when I bought the SE-1X from Studio Electronics, the spectrum opened up even more. It’s very possible to get the same results or even better with software, but in my particular case the fact of being able to save time, the sound quality I could easily get and the satisfaction of working with that machine made it one of the main parts of my studio. I have never used a plug-in to compose a bassline again.

However, at this point, I should note that I haven’t always been that lucky when choosing and buying machines. I didn’t get used to many of the machines that I purchased so I ended up selling them—but this is another positive part of the hardware: you can always sell and/or renovate tools that you don’t like or don’t use. However, today I can proudly say that I have worked hard on developing my studio and now I can use any piece of equipment I have on almost every track that I make.

Drum machines are possibly the field where the character of each device and brand is the most noticeable. For this reason, I have five different drum machines in my studio and I try to combine them in different ways all the time. Also, when you have different step sequencers, these are some of the easiest machines to manipulate while recording live arrangements. That’s how I always produce, and that’s what gives me the best results.

Finally, we must discuss sound quality. It’s been a bit over four years since I started building a modular synth. Obviously the process wasn’t as easy as going to a store and buying a finished synth, mainly because of the price but also because a lot of these modules are manufactured by small companies who take some time to deliver and therefore you have to order them and be patient. My creative spectrum and my overall knowledge about synthesis improved a lot in a short period of time. I would have never come even close to that if I didn’t have this new tool, that also has the capability of expanding or changing in structure according to your evolving needs. The sound quality is way superior than any of the software synths I tried and it has really awakened a lot of interest in further expanding my knowledge and skills in this field. It’s almost like a child’s game to make sounds and experiment with this system, not because of its simplicity but because of how intuitive and entertaining it is. There’s a high surprise factor and very often it feels like the sound is somehow alive, which really stands out when you listen to the music. That is also one of the main reasons why I choose to work with machines.

“Just using a good mixing desk, good converters, a nice analog compressor, and a nice EQ, puts you in a different place and brings lots of advantages in comparison with what the virtual world has to offer.”

The final overall sound is possibly the most special of all, and in my personal experience this is the field where it’s the most difficult to replace hardware with software (even though it’s not impossible). Just using a good mixing desk, good converters, a nice analog compressor, and a nice EQ, puts you in a different place and brings lots of advantages in comparison with what the virtual world has to offer. A very good friend and well known producer once told me: ‘’I didn’t listen to what a compressor does to the sound until I bought my first analog one,” and I have to agree with him: there’s a huge difference between a plug-in and a real compressor. I also heard Mike Huckaby once explaining how he achieves such a particular sound and he named some very expensive converters. He also said that the people asking didn’t like to find out what the reason was. The mixing desk is the heart of the studio setup. It’s not only an instrument by itself but also probably the most important of all. Everything goes though it. Especially the way I record, in one take and to only one final stereo track, the desk I use has to offer a lot of possibilities to connect hardware in different ways and to obviously have a great summing capability.

So now we must go back to the beginning. Like I mentioned above, we live in anarchic times where there are thousands of possibilities for setups and we’re all free to choose how and we with what we make out music—ranging from a laptop and sound card only, to a setup where you don’t even need a computer to record. It is, however, your choice; but in my particular case, the fact that I have switched exclusively to machines has enhanced both my creativity and curiosity, and has transformed the act of making electronic music into a very entertaining venture.