Real Talk: Mark Fell

The UK artist recalls how the house and techno wave has impacted the wider European electronic music scene.

Real Talk: Mark Fell

The UK artist recalls how the house and techno wave has impacted the wider European electronic music scene.

This months’ Real Talk comes from Mark Fell, the Rotherham-based artist—recognised for his writing and creative exhibitions/installations in addition to his music. With regards to the latter domain, Fell is known for his work alongside Mat Steel as SND, a collaborative project with releases on Raster-Noton and Mille Plateaux. Elsewhere, he’s released several albums under his own name, under the moniker Sensate Focus, and in various other collaborations. Having started in the late ’90s, he’s established himself as an innovative, versatile, and prolific electronic producer.

In this edition of our Real Talk series, Fell recalls the emergence of house and techno in Europe and explores the long-term implications for the wider electronic music landscape. Looking back, Fell explains how the period of 1988 to 1992 marked “something of a turning point,” prompted by a shift in the position of dance music from the margins to the centre of a wider cultural landscape. Alongside an exploration of just how these changes happened, Fell also gives his thoughts on the social and technical changes that took place during this time.

A couple of years ago, I was asked to present a sound installation (Structural Solutions To The Question Of Being) as part of Art Sheffield in an old derelict pub at the centre of a derelict brutalist housing project on the outskirts of the city—the infamous Park Hill. After months of increasing panic, as I struggled to meet the deadline, the project sort of resolved itself while listening to an old mix tape with my friend Terre Thaemlitz—who many of you might know as DJ Sprinkles.

Originally broadcast on a local pirate radio station back in 1992, the show was presented by two friends: Rebecca Seager (my classmate at art school who introduced me to her boyfriend Mat Steel with the line, “he’s into Derrick May”); and Solid State (a resident DJ at many of the early house and techno nights in Sheffield). Halfway through the tape, Seager announced a “shout out to Mark in Rotherham.” The message took over 25 years to arrive at its intended destination but evoked memories of the musical, technical, and social changes that were taking place.

As Terre and I listened to the old mixtape, we talked about the importance of this period (around 1988 to 1992) in our own personal musical histories. Although we grew up in quite different places—both geographically and culturally—it seemed that for both of us these years marked something of a turning point, perhaps prompted by a shift in the position of dance music from the margins to the centre of a wider cultural landscape. Here I want to discuss this shift. And, from my personal perspective, as an avid listener and embryonic producer, consider some of the technical changes that took place at this time.

Structural Solutions To The Question Of Being

Photos: Julian Lister

CLICK ANY PHOTO TO ENLARGE AND ENTER GALLERY BROWSING

At the time of the mix, I was coming to the end of my studies at Psalter Lane Art School. My enrolment in the three-year course in experimental media three years earlier roughly coincided with the release of Forgemasters’ seminal work “Track With No Name”—which landed in 1989 on Warp, a new and unknown label at that time.

As is so often the case, the art school was inextricably interwoven with the city’s various music scenes. In the late ‘80s, with the onset of Sheffield’s “techno era,” Psalter Lane not only provided event spaces, but more importantly gave us access to technical resources: digital video editing and processing, sound studios, crude computer graphics systems, and so on. The majority of its students were part of Sheffield’s music scene to some extent: Phil Wolstenholm, for example, designed many of the images used on early Warp covers; others were DJs or producers; many made visuals for parties; a few danced; one or two just listened and watched from the perimeter of the dance floor. This is where you would find me.

Although there was a constant flow of students from the art school into the underground techno world, the relationship between the institution and the dancefloor was not always an easy one. The tutors, for example, had a limited understanding of this world, not only in the use of sound in creative practice but also the particular musical and cultural references that we were dealing with; they just didn’t fit into the tutors’ vocabulary.

I remember a particularly unfruitful meeting with the British composer Trevor Wishart when, around 1990, he was called upon to meet a bunch of students attempting to work with sound. I was trying to do something like the chord stabs on “Big Fun” (Inner City, 1988) but “like, more messed up and weirder.” Unsurprisingly, he clearly didn’t get our aesthetic position. Because of our constant struggle with this issue, most of us decided to split our artistic interests into things that could be assessed and things that could not; anything that could be danced to fell into the latter category. Unfortunately, having met many students in recent years, I think this division still operates today. While researching another project, I recently asked Wishart if he remembered this meeting, but he claimed to have no memory.

“I remember a guy once threatening to throw me out of a party at his house for playing some early techno, presumably because it lacked the authenticity of the Hawkwind that I switched off, only to see him two years later with a shorter haircut, change of wardrobe, glowstick in-hand, raving his tits off.”

Despite my peripheral location around the edge of the dancefloor, it seemed for those years (1989-1992) as if I was at the heart of some kind of movement: dissatisfied with an increasingly conservative social policy, our collective consciousness was firmly focussed on alternatives, and we came together in club spaces.

This movement seemed to grow and grow. I remember a guy once threatening to throw me out of a party at his house for playing some early techno, presumably because it lacked the authenticity of the Hawkwind that I switched off, only to see him two years later with a shorter haircut, change of wardrobe, glowstick in hand, raving his tits off. It seemed like everyone was converting to the club habitus: with exponentially increasing drug use, longer weekends, larger venues, bigger sound systems—and this is how it went on and on. The increasing scales meant a shift from city centres to forests and quarries; pirate radio stations would guide us down pitch black impossible dirt tracks, into the night, following the distant reverberation of kick drums. (Actually, that was the best bit; once you got there it was cold and boring).

“….when I was making mix tapes I would think nothing of placing some kind of techno track next to acid house. Not because I was being ironic, but because, although clearly not the same, they appeared to be very similar.”

I think my first sight of this cultural shift came in 1986 with early house releases, and soon after I was given a fourth generation copy of a cassette of Detroit techno. I think acid house was sweeping the nation by late 1987. Although in retrospect I make these stylistic distinctions, at the time all this stuff felt somehow part of the same general category. For example, when I was making mix tapes I would think nothing of placing some kind of techno track next to acid house. Not because I was being ironic, but because, although clearly not the same, they appeared to be very similar. That apparent similarity now seems pretty naive; but it only seems so because of the increasing focus on such musics over the following years, because of their growing centrality in a hypothetical musical universe.

For me, these differences—although present in the musical preferences of Sheffield’s many DJs—had not developed to the point of justifying separate nights, distinct dress codes, or ways of behaving in social contexts. They seemed like minor stylistic differences—points of emphasis that until now had remained to some extent nameless. But, after its initial appearance, with its move to cultural centre ground, this pseudo-singular movement began to fragment into multiple versions of itself—producing distinct sub-genres, each with its signature sounds, rhythmic structures, and typographic preferences.

And coming back to the old pirate radio show, this initial moment of fragmentation felt somehow present within this mix of music. It was around this time, in Sheffield’s specialist record shops, that new category markers were added to the racks, surreptitiously structuring our searches: hardcore, deep house, trance, progressive, jungle, and so on. Similarly, labels began to occupy their own locally divided spaces: Transmat, Nervous, Guerrilla, Warp, Strictly Rhythm, for example; each offering related yet distinct perspectives on the previously “singular” dance planet from which they were somehow departing. Within my community, a collective understanding of this complex musical multiverse began to emerge, an understanding formed around these apparently inert plastic category dividers.

From this point forward, we searched with heightened aesthetic precision, with an increasingly refined tribal literacy, with a logic we had previously not known. Finally we would ignore the sections that were of lesser interest, and consequently, we began to occupy different spatial positions within and around the shop itself; we became physically separate, divided by categorisation. At this point, the markers polarised our interests even further, and the record shops themselves were positioned within these categories, each within its own particular specialism. Or, at least this is what it felt like.

Commensurate with these shifting musical constructs were equally complex technical changes. The familiar narrative here is one of widening access to techniques like sampling, the rediscovery of economically unsuccessful drum machines and sound modules, and the dominance of new protocols such as MIDI. And clearly, these factors largely changed not only how music was made but the very structure of the music itself.

But analyses of technical change throughout this period often overlook the fact that 1989 not only saw the introduction of the first graphically organised “timeline” sequencer developed by Steinberg (originally called Cubit, later renamed Cubase for legal reasons), but also the first commercial distribution of a lesser known programming environment by Opcode (“Max”, recently acquired by Ableton).

I believe that the now familiar musical vocabulary present in house music not only evolved in response to sampling, MIDI, and the rediscovery of the TR808 or TB303, but also to some extent the features of timeline-based sequencing and editing—of distinct layers of musical information positioned within a linear-time format.

The timeline promotes a creative methodology that is quite different to using a TR808 or TB303 where patterns are encoded within loop-based systems and changed as the music plays. There was and still is something insanely engaging about changing patterns on the TR808 as the music is played. But when the timeline began to dominate studio practices—following the introduction of Cubit (above)—the sorts of ways of working that the 808 and prior analogue technologies had facilitated seemed to be pushed out of studio practices. Therefore, even though the 808 is credited as a primary tool in the production of early house and techno, the later tool of choice for many producers (the timeline) ultimately excluded it.

“Timelines changed the musical vocabulary of house in a way that I did not like.”

My feeling was that its greatest strength was also its greatest weakness: namely that it encourages the producer to visually organise material over a linear time logic; to work from a kind of pseudo-objective point outside the music. The timeline enforces a particular kind of temporal structure and also a particular kind of temporal disengagement.

Undoubtedly, this methodology is very useful, and in some ways far easier to operate than older pre-timeline systems. For example, if you have a bunch of musicians playing a song and you want to record the whole lot and then edit out the mistakes; similarly if you are a classical composer and you plan your work in a score like format and you can simply enter it into the computer—the score and the timeline have a close structural similarly. But as an environment within which ideas are generated, the timeline places the producer in a very specific relation to musical materials. Beyond the very basic recording of musical events and parameter values, the timeline producer is compelled to stop, record, play, rewind, edit, move forward. These behaviours that are quite unlike the process involved in using drum machines and other musical instruments. Similarly, editing became a visual operation: looking at structures and the information they contain. Timelines changed the musical vocabulary of house in a way that I did not like.

My dislike of this environment is increased to the extent that many temporal changes (within a given piece of music) feel somehow fake. I understand that the word “fake” in this context is a little problematic. But what I mean is how the flow of time and energy is presented as a kind of illusion.

Think, for example, of the popular TV show “Jools’ Annual Hootenanny” which is broadcast every New Year’s Eve on British television. It features a collection of musical celebrities acting out some hideously grotesque end-of-year ritual. As an audience, we are led to assume that the programme is live—that those celebrities share the same moment of annual transition with us. The illusion it constructs is that we are collectively together in welcoming the new year, and as the clock ticks past midnight their cheers are not only apparently but actually synchronised with our own. But the illusion utterly fails when we realise that the show was actually recorded several days earlier, and the entire collection of guests are complicit in the delivery of some carefully orchestrated lie. It just seems like a manipulative con trick.

It feels similar to me when club music attempts to manipulate energy levels—with familiar devices such as breakdowns, snare rolls, the opening of filters, and extending volume envelopes. The pretence of constructing a seamless flow of musical events just reads like a kind of badly constructed illusion, a manipulative lie that masks the processes that brought it into being. Of course, this isn’t a problem for everyone, but for me, it only served to reinforce my creative and conceptual difficulties with the timeline.

I feel that house music still contains this sort of internal contradiction: certain elements of its vocabulary are based on an elementary mismatch in temporal relations. Like a wallpaper that tries to imitate expensive oak cladding, it might look nice or even have some kind of kitsch appeal, but ultimately it is based on the echo of a prior cultural language with its grounding in quite different materials and processes; it is primarily concerned with the promotion of lifestyle choices. I’m not saying house music is bad because it is a poor copy of “real” music, but rather, that in my opinion house music is best when it does not aim to copy “real” music. Similarly, my favourite wallpaper (i.e. wood chip) does not aim to imitate oak cladding.

Beyond these conceptual issues, I was definitely not alone in my frustration at working with the timeline environment. I can clearly remember several conversations with my peers about these problems. I remember, for example, when the facility to record track mutes in real-time was implemented—I think in Logic—or how the Yamaha RY30 drum machine allowed one to assign different patterns to different keys so that that they could be triggered and switched between without having to press stop. Pressing “stop” not only stops the music; it places you (the producer) in a different relationship to the materials, and in a very different head space. Although the producer of a stopped track might still be fully engaged with the track, the nature of that engagement is quite different to its played form. I found that I could not make meaningful decisions about the structure of a stopped track, yet I could make meaningful choices as the track was playing. So these minor developments (recording track mutes or real-time pattern switching) might seem quite crude, but at the time we welcomed them precisely because we didn’t have to press stop, rewind, edit, play and so on. The choices we made were embedded within the temporal logic of the music, not imposed from a temporally detached position outside it.

Looking back at this period, I think there are also interesting points to be made about the impact of North American dance music on the kinds of electronic music that were coming out of Europe. In particular, I think that many producers associated with the European “industrial” music scene (beginning in the late 1970s) moved increasingly towards dance music production techniques and structures.

“I think this functioned as a kind of behavioural template into which the later house and techno imports would fit.”

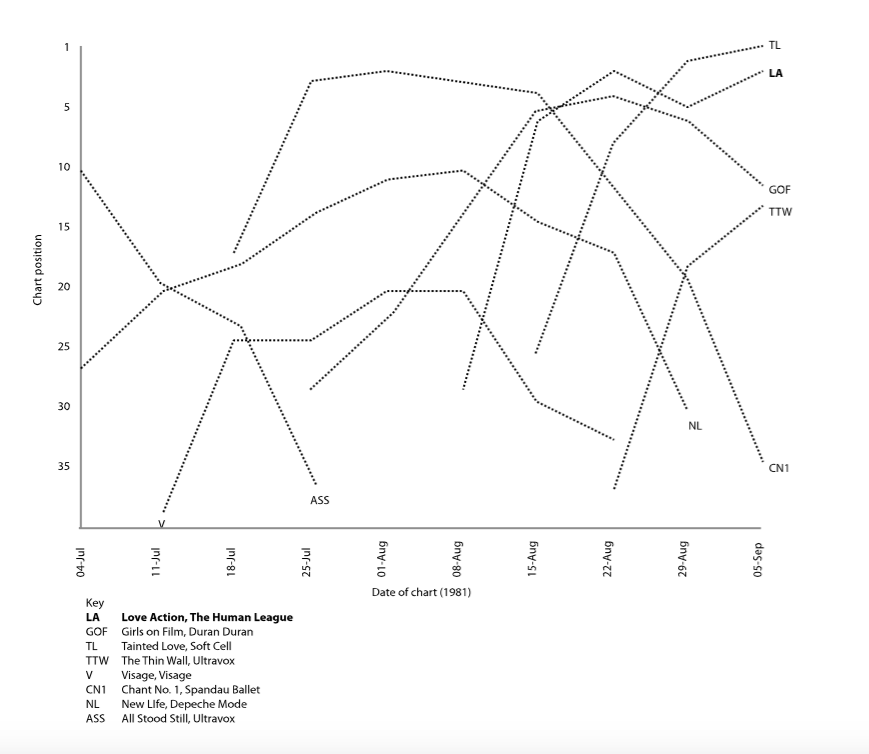

I guess I’m interested in this interplay because the development of my own music practice too came about in response to it, and I think it also applies to many of my peers. Like many of my generation, my first encounter with overtly “electronic” music was the synth pop of the early 1980s. This peaked in August 1981 when the top end of the British singles chart was saturated with breakthrough records from The Human League, Soft Cell, Depeche Mode, Duran Duran, Visage, and Ultravox. The appearance of these synthesizer wielding newcomers over successive Thursday evenings irrevocably changed British popular music: punk’s overt oppositionality replaced by synth pop’s somehow understated gender deviance. I would also argue that there was an implicit understanding that this music was dance music, and the kind of dancing you did in response to it was very different to the movements one might encounter at a punk rock gig. I think this functioned as a kind of behavioural template into which the later house and techno imports would fit.

If we rewind a little further, to the late 1970s, although the popular music environment was dominated by the latter end of punk rock and the revision of Ska music, in the background were a number of primarily electronic music projects associated with the Industrial Records label, forming what loosely became known as “industrial music.” Although this term clearly revolved around Throbbing Gristle, other projects often aligned with it include Cabaret Voltaire, Einstürzende Neubauten, Clock DVA, and others. At the same time, Daniel Miller began to explore electronic music with projects such as The Normal. It is often assumed that industrial music was essentially noise and chaos, but actually to me as a follower of the genre, it seemed to have an equal and parallel focus on being dance music. Indeed, much of Throbbing Gristle’s catalogue includes dance music: Hot On the Heels of Love (1979), United (1980), Adrenalin (1980); even Discipline (1981) is basically a looped groove. Similarly, the vast majority of Cabaret Voltaire’s output at this time was electronic, repetitive, rhythmic: a format that would later be cited as influential by many North American house and techno producers.

In the period following the shimmering golden years of synth pop, many of the producers associated with the earlier industrial moment became increasingly focussed on newer technologies—because of their position within the industry they had to some extent privileged access to processes that were beyond the reach of unknown producers.

Although coming from electronic music’s backwaters, many of these more established producers developed their interest in more unusual forms of dance music. Following the split of Throbbing Gristle, Chris and Cosey (under the name Conspiracy International) released a number of 12”s singles that sound almost like the early ancestors of minimal techno. Current 93s single “Lashtal” (L.A.Y.L.A.H. Antirecords, 1984), although not dance music could certainly be danced to with its combination of sampled rhythmic structure and synthetic texture. After the release of “Zeichnungen Des Patienten O.T.” (Some Bizarre, 1983), Einstürzende Neubauten, famous for their appropriation of metal objects and industrial machinery, brought sampling technologies into the equation, resulting in “Halber Mensch” (Some Bizarre, 1985) giving some of their rhythmic structures a distinctly danceable feel—most notably Z.N.S and Yü-Gung (Fütter Mein Ego). The latter piece was remixed for single release by Adrian Sherwood, an increasingly prolific dub reggae producer whose work with Tackhead formed a bridge into the world of electronic dance music to come. Similarly, Test Department began to focus on the use of sampling technologies and in 1986 released “The Faces Of Freedom 1 2 & 3” (Ministry Of Power). Although I loved this record, when I listen back to it now I’m struck by its clear associations with an earlier musical paradigm: the large heavy snares, the use of gated textures and so on—all these were about to become insanely dated in the few months that followed. It seemed as if all those producers associated with the pre-synth pop moment were getting more and more fixated on dance music, a fact made all the more visible with releases such as Funky Alternatives (Concrete Productions, 1987), a series of records that borrowed with varying degrees of success from the language of electro, hip-hop, or hi-energy.

While the emergence in Europe of house and techno was clearly not invented by this earlier generation of mainly European producers, its arrival here was eagerly adopted by those producers. It was around this time that I received the fourth-generation cassette of first-generation Detroit techno, handed down through a string of friends that I think started with Robert Baker, a member of Clock DVA and The Anti Group. These guys were slightly older; always seemed slightly more informed than me; they knew friends of friends of colleagues etc. forming networks which (I imagined) eventually crossed across the Atlantic and into the sacred birthplace of techno.

And, in an interesting twist of fate, during the recording of “Big Sex” by The Anti Group (what a title) Robert Baker coerced the studio engineer Robert Gordon into attempting a remix. The result I think was Gordon’s first musical release. And soon after he met Winston Hazel, going on to write and produce “Track With No Name” (Warp, 1989), the inaugural release that would develop into a movement in its own right. Of course, this didn’t happen because The Anti Group invited him to do a remix, it’s is just an interesting part of the story. For me what is most interesting is the comparison between Rob Gordon’s mix of “Big Sex” and “Track With No Name.” Although there are similarities in terms of patterns and sounds, there is nonetheless something of an aesthetic jump between the two pieces, a difference that ties them into different generational divides.

To sum up, if you think of the emergence of house and techno as a kind of tsunami that swept across the musical landscape, what was left of the earlier industrial tradition seemed almost unsalvageable. Cabaret Voltaire, in the wake of techno’s happening, seemed resigned to producing slightly less convincing copies of it—I’m thinking of their 1990 release “Keep On”. (I should mention however that Richard Kirk’s collaborations with DJ Parrot under the name Sweet Exorcist (Warp, 1989) were in my opinion more successful.)

It was in this landscape that I was trying to develop my own practice: to do something like the chord stabs on “Big Fun” (Inner City, 1988) but “like, more messed up and weirder.” It is no wonder Wishard did not have an answer as it took me another six or so years to make any progress on the problem.

Returning to the present day, the mix is still playing, Terre and I are still chatting, actually, as usual, it’s broken out into a full-scale argument. But one thing is clear: the mix is worth investigating. I managed to get back in touch with the two DJs to arrange a discussion with them, and to my surprise discovered that the mix was broadcast from a vacant flat in the now derelict housing estate. “Structural Solutions To The Question Of Being,” my sound installation, opened in Park Hill soon after. Its central focus was the mix, functioning as a route into analyses of the wider political, social, chemical, technical, and musical upheaval of the period.

What I hope to have conveyed here is a sense of just how important the years 1988-1992 were not only for the musical innovation that took place but perhaps more importantly as a marker within a larger cultural shift.

__________

Thanks to Terre Thaemlitz, Mat Steel and Ed Martin for their advice and comments.

Support Independent Media

Music, in-depth features, artist content (sample packs, project files, mix downloads), news, and art, for only $3.99/month.