Rewind: Adult.

The media can be ruthless with its prescription of genre labels—once something has been assigned […]

Rewind: Adult.

The media can be ruthless with its prescription of genre labels—once something has been assigned […]

The media can be ruthless with its prescription of genre labels—once something has been assigned a particular stylistic tag, it’s often an uphill struggle for an artist to grow out of it. Just ask Adam Lee Miller and Nicola Kuperus, the married couple who, for the past 19 years, have recorded together as Adult. Both art-school trained artists, Miller’s and Kuperus’ anxiety-addled sound and unique, extra-musical narrative was brought to popular attention in the early aughts when members of the press began lumping them in with Larry Tee’s then-nascent electroclash movement. Granted, the association did bring the group a lot of attention, but it also threatened to pigeonhole the two Detroiters into the New York club-kid culture’s fad of the moment. Much of Adult.’s career since has found the pair pushing against the electroclash tag and the expectations that come with it—resulting in a body of work that’s unconventional in the way it consistently defies expectation. This week marks the release of The Way Things Fall, the duo’s first LP since 2007, so we asked Miller and Kuperus to sit down with us and recount many of the pivotal moments of their long career.

Plasma Co. “Modern Romantics” 12″ (Electrecord, 1998)

Adam Lee Miller: I was in a band at the time called Le Car, and I also did a few solo releases, but nobody really cared about them—which is fine now, but it wasn’t then. [laughs] And so I got a phone call from a German record company that wanted to put out a couple of my songs on a CD compilation, but [during] the whole phone conversation, I thought they [were interested in] Le Car because we were doing okay. So, suddenly I said something, and they said, “No no no, we mean Artificial Material, your solo stuff.” Nicola and I were dating, and, basically, I didn’t want to go to Europe by myself, so I just held my hand over the phone and said to Nicola, “Do you want to go to Germany?” And she said, “Yeah!” I got back on the phone and said, “When I tour solo, it’s still a two piece to perform live,” and they said, “That’s fine. We’ll send two tickets.” So that’s exactly how it started. We had to write enough music to play live, and so we ended up writing 45 to 50 minutes of music. !K7 was the money behind [the trip], but it was [organized] by a smaller label called Electrecord. We toured with Electrecord, and they asked us, “Can we put out some of your music from your live set?” And we said yes, but then we realized that it wasn’t my solo music anymore because we’d written everything together. We were like, “Well, we’ll just change the name to Plasma Co.” And so we put that out, but for some reason right away we didn’t like Plasma Co. So after that first 12″, we switched to Adult.

Nicola Kuperus: It’s really just this joke we have, because we got the Plasma Co. name from a sign on Woodward [Street in Detroit] that was like this old…

ALM: You donated your plasma.

NK: Yeah, it had these really great letters that said, “Plasma Co.” But it was always a joke because across the street it says, “Adult”—there was an adult bookstore.

ALM: Also, there was a genericness to [Adult.] Obviously, we put the period after it to try and make it more unique, but that was [thought of around] the birth of the internet, so we never really considered how hard that would be for searching [the web].

NK: Yeah, like, just try and Google “Adult. live.”

Dispassionate Furniture EP (Ersatz Audio, 1998)

NK: I remember writing that record and laughing a lot. At the time, this was like ’98, there weren’t a lot of weird vocals in electronic music. It just wasn’t popular, what we were doing. We weren’t in an indie market, we were in a total techno market, so I just remember a lot of times being like, “Oh my god, people are going to hate this. It’s going to be hilarious. They’re going to be like, ‘Why are they singing about furniture?'” And when we went to Germany for the second time, people would come up to us and look at us like, “What are they doing?” [They’d] ask us, “Where’s the 4/4 beat?”

ALM: They would ask us to play something else in a live set. They would walk up and say, “Can you play something else? Something more house?”

NK: I’m not really sure why we picked to talk about furniture for an entire album. I almost feel like it was sort of like a “fuck you” to both worlds.

New Phonies EP (Clone, 2000)

ALM:New Phonies on Clone [gave us our] first bit of attention. It had “Hand to Phone,” and it did well. Nicola did an amazing job with the photographs on that picture disc. And with a picture disc, it’s like, “Why did you do a picture disc? It’s ugly.” I mean, I think she did an amazing job. It’s just a beautiful work of art. So those two things—the artwork and “Hand to Phone”—really helped [us]. That’s where it started.

NK: I think we also realized that there’s so much more visually that we could be doing.

ALM: Yeah, because we both went to art school, this was very much to us an art project more than a band.

Nausea EP (Ersatz Audio, 2000)

NK: When we made Dispassionate Furniture, it was like that thing where you want what you’re doing to be successful, but then sometimes there’s this weirdness that can come with it as well. So when you’re writing, you’re being really tongue-in-cheek and sarcastic—I think that’s where the whole theme of nausea came from, it was just like some kind of frustration with people liking what you’re doing.

ALM: Everything we do has a sense of play, but it’s also very personal. So, I mean, we were kind of making fun of people with tons of phobias on Nausea, but we were also making fun of ourselves. I mean, it’s like Nicola was just saying: You want it, but then you get it and… I don’t know. I think that—partly because we’re such traditional, damaged artists—in a way, if it’s too popular, then you don’t think it’s real art. So you don’t want to get too popular because you’re like, “Oh, we’re not making real art.” But then you’re like, “I don’t want to work a real job,” so it becomes this weird struggle—but a good struggle. And I don’t know… Looking back, we were so young that we just were not prepared for it.

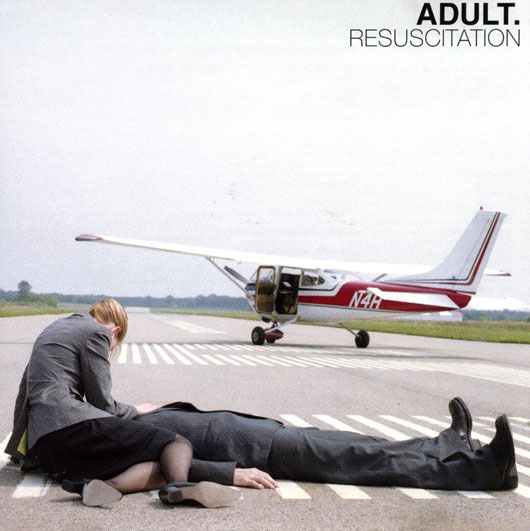

Resuscitation (Ersatz Audio, 2001)

ALM: We released Resuscitation in 2001, but to us, it was old because it was [a reissue of] all older records. October 2001 was when the Electroclash festival happened in New York with Chicks on Speed and Peaches and us. It was so strange because it was so much, I don’t know, pre-hype that it was going to be some movement. We were just laughing because the joke at the time was that we had played a festival called Biofighters, and we were like, “Nobody’s running around saying that Biofighters is some new genre.” It really took us by surprise, and we really felt used. You could feel that ugly side. You always hear people talk about the ugly side of Hollywood or the music business, and it was like, “Wow, these people don’t care if you like it or not, they’re going to lump you in so they can make a profit.”

NK: Right. So the media just created this electroclash scene, and just because we played that festival, we were [said to be] a part of it. And, um, we were really put off by it. And you know, we fought for a couple of years against that label. We always felt that, since Larry Tee is from New York, [electroclash] is more of a New York scenester kinda thing. Whereas we’re from Detroit, so we don’t operate that way. We had been working at that point for people to take electronic music seriously, but then we were getting paired up with somebody who just puts the soundtrack to Flashdance on and pours buckets of water all over themselves. Then [we thought], “What am I doing here?” [We’re] not like a fucking dog-and-pony show. This is our music, and it’s very personal to us. To just feel like it’s all a spectacle was very irritating.

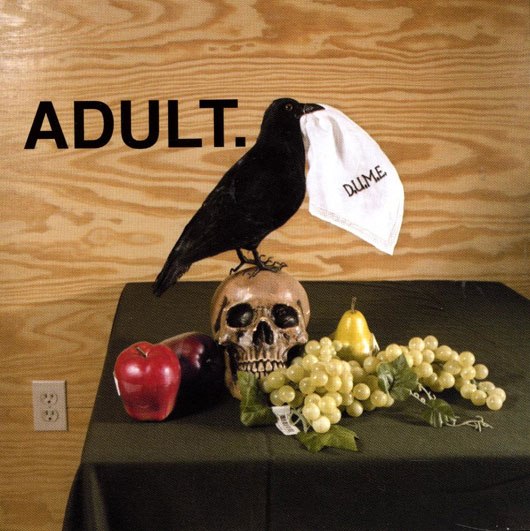

D.U.M.E. (Thrill Jockey, 2005)

NK: The name stands for “Death Unto My Enemies.” It was really [about us] trying to shed our skin or something. We were still mad at a lot of the media and their categorization [of us]. I think that’s also the first time we put guitar on our record. And I think that it’s interesting because, since [around the record’s release], the landscape of music has made a big shift—it’s now not uncommon for an indie-rock band to have a synthesizer. Whereas before, dance music and indie music didn’t talk to one another. They were incredibly separate, and I felt like it was a pretty big shift at the time.

ALM: We got so much shit for putting guitar into an electronic band. But I think, as our discography proves, we’re kind of used to whatever crap we’re getting. But what happened was that once we finished D.U.M.E., we realized we couldn’t perform it live because it had bass and guitar [on it], so we asked a friend of ours—who was in a band called Tamion Twelve Inch that we released on Ersatz—to go on tour with us. Adult. was Nicola’s first band, and I think she really wanted to experience a more band environment. And I think that’s another reason it became the album that it became. At least for us, we’ve always got to be moving forward and pushing ourselves. It’s like Woody Allen said, “Relationships are like a shark, and if it’s not moving forward and eating, it dies.” That’s like our band.

NK: I think we pushed. I think we were trying really hard to get out of the electroclash thing, and get out of where we were and what our sound was.

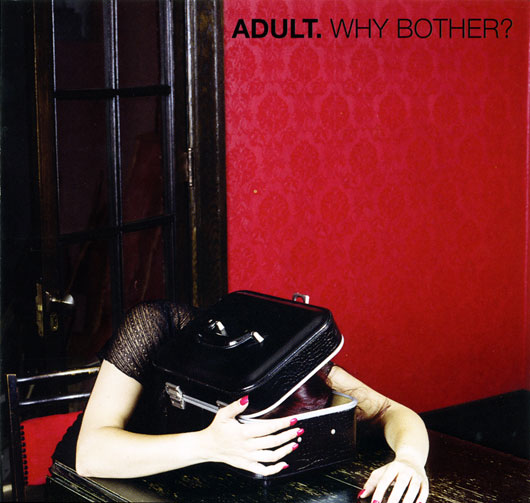

Why Bother? (Thrill Jockey, 2007)

ALM: We didn’t realize it at the time, but looking back, I find it so interesting how [Why Bother?] really foreshadowed that we were getting burnt out. When New Phonies and Nausea came out, we were playing seven shows a year. D.U.M.E. and Gimme Trouble came out, and we played 53 shows a year. We were really starting to get burned out.

NK: Then, the next year we did 46 more shows. And, you know, I think it’s interesting that it was called Why Bother?. I think it was kind of almost the end. We even titled the kind of music we were making “uneasy listening music.” You know? There’s a lot of moments on that album that are just plain ugly.

ALM: One of the important things about Why Bother? was that it was the first album that we had done two music videos for ourselves. And that really satisfied us because we had really [got to a point that was just] “music, music, music,” and we weren’t doing enough visual things as well. So that was a really important part of that record, making the videos. “The Folk Trilogy” really took a lot of visual themes that we both always worked with and made [them] into a short film. With Nausea, we added this other component to the music—the album art and everything—and I think the videos [we made] expanded upon that. [They] really helped to let people into this bigger world that’s in our heads.

Decampment: Parts 1-3 (Ersatz Audio, 2008)

ALM: So, once we built a music video for “The Folk Trilogy” it satisfied us on so many levels, and we were just like, “I don’t want to get in the van anymore and tour around.” And we said, “Then let’s stop. Let’s not do another album.” And then we started coming up with ideas for a more extended video, and then the Detroit Institute of Arts called us. So we had the financial support from them, we had the ideas, and we’d gotten the bug from doing the five-minute music video, so we made the 40-minute Decampment film.

NK: It was more of an art piece.

ALM: Yeah, it was really funny when we put out the Decampment 7″s. Each one came with a photograph of Nicola’s. And normally her photographs go for a decent amount of money, so we thought, “Okay, we’re going to limit each of these to a 100. There are three in the series, and they’ll be $100 apiece.” And it was really funny how everyone we knew in the art world was like, “Wow, that’s so cheap,” and everyone we knew in the music world was like, “You guys are pompous assholes, this is ridiculous.” That’s when we knew we had the balance right.

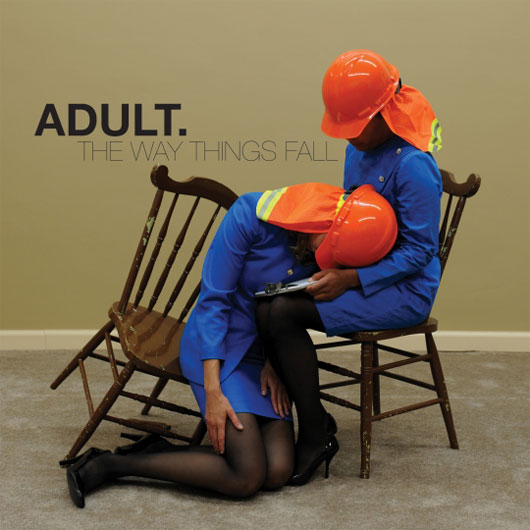

The Way Things Fall (Ghostly International, 2013)

ALM: So, for the past three years, Ghostly has wanted to re-release Resuscitation because it was out of print—which we always thought was a great idea, but the timing just never seemed good.

NK: So the agreement was: We’ll re-release Resuscitation with a follow-up 12″ record that comes three months after. We started writing songs, and then it just started getting to the point where we wanted to overwrite. Because, really, sometimes life moves so quickly that you don’t get to edit out things as much as you want to. And we wanted to market the best 12″ possible. Then it got to the point where we were like, “Well, which song will we get rid of?” Then we said, “Maybe we should just keep writing,” because the writing process was so amazing and fulfilling. It almost felt like an exorcism of a lot of stuff. It was a really good cathartic process.

ALM: Yeah, and by that point, we just didn’t care about what used to bother us. Somebody in an interview said, “People are now calling you ‘electro batcave’.” And we were like, “Whatever they want.” So, really, we could care less. It’s funny because people talk about the new album being much more personal and the earlier stuff being about society at large. We were always fighting society, and now we don’t care.

NK: At this point, if people don’t understand who we are or why we do what we do, then fuck ’em. You know? I can’t argue it anymore. I don’t have the energy.