Studio Essentials: Aspetuck

The key gear behind Griff Fulton's work.

Studio Essentials: Aspetuck

The key gear behind Griff Fulton's work.

Aspetuck, real name Griff Fulton, is an American DJ-producer from Vermont, northeastern United States. Cut off from nightlife, he and his younger brother, Pierce, jammed together on guitar and drums in their basement, encouraged by their music-loving parents to pursue their wildest musical whims. While he never took drums seriously, Fulton developed an “obsession with rhythm,” he says, which influenced the way he relates to music. He discovered new music through snowboard videos, and these exciting new flavours dragged him down the wormhole that is electronic music. “That exciting feeling of stumbling upon something special you never would’ve expected is something that has stayed with me in a major way,” he says.

It wasn’t until he moved to Brooklyn after college that Fulton experienced nightlife for the first time, and it became his obsession. He’d go out clubbing with friends, intent on interacting with whatever new genres he could find. When he later moved to Los Angeles, where he’d attend illegal raves across the city, he began to consider making the music that was consuming him. A few years later, after an epiphany during 2017’s Amsterdam Dance Event, he purchased a basic setup and began to experiment, and that’s where it all began. “It was like an explosion of ideas and I cannot believe the effect it has had on my confidence as a person,” he recalls. When he self-released some early tracks, including a debut album, he caught the ear of Route 8, who signed him up for The Time Capsule Experiment.

Though crafted in the clubs of Los Angeles and Brooklyn, Aspetuck’s work is heavily influenced by the rural life he’s led for much of his life, and has since returned to. While each track, including those on Distant Messenger, his latest EP, would make a dancefloor shuffle, they’re equally enjoyable for putting on in private. His work is underlined by a fascination with percussion and the influence of dub on electronic music, and it pulls heavily from breakbeat, house, and electro. We discovered Aspetuck after he submitted music through the XLR8R submissions portal, and more recently he’s submitted a pair of original tracks as part of the XLR8R+30 package.

The tracks, “Doldrums” and “Itchy,” both sit loosely in the house music realm and encapsulate what we love about Aspetuck’s music; namely, subtle atmospheric textures, intelligent grooves, and patient arrangements that coax the listener into a dream state of electronic bliss. In the edition of Studio Essentials, he walks us through they key pieces of gear behind his work.

I started out making music on my computer with Ableton but I’ve decided I want to incorporate more of a personal touch into what I’m making by not relying on my computer so much. While I love using Ableton for making loops and processing recorded sounds, using the computer to automate various parameters on a synth isn’t exciting to me. It tends to sound a bit robotic and it’s a tedious process; I’d rather twist a physical knob on a synth and record something in one take rather than meticulously click and drag automation points for hours! It has taken a lot of trial and error for me to find the right gear, but recently I’ve just been spending as much time as possible with various synths to see how I can best integrate them into my workflow.

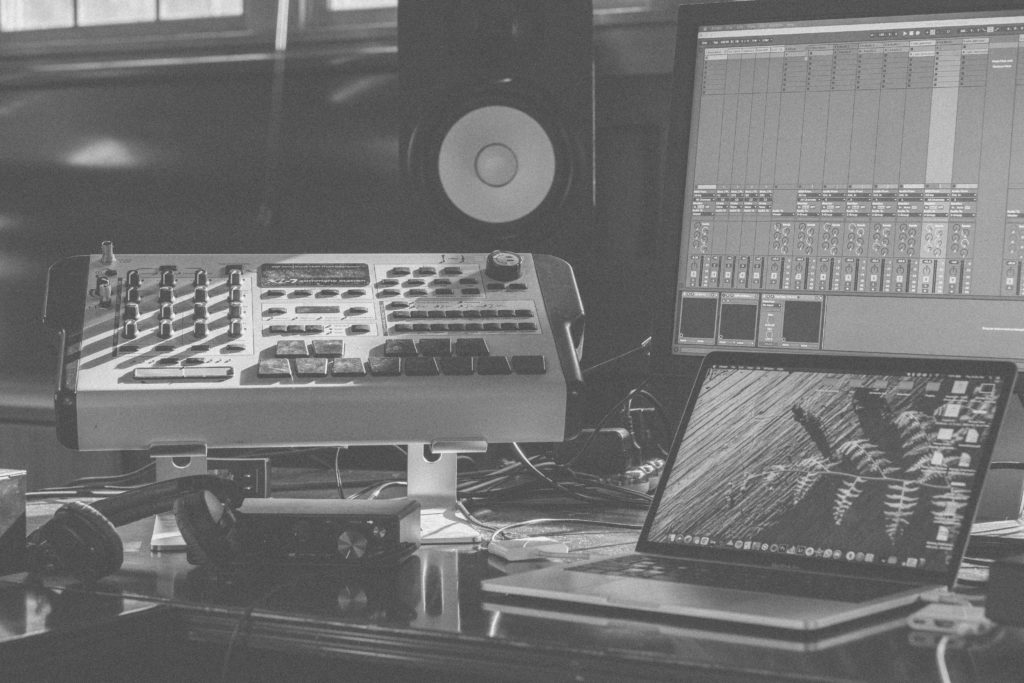

One of the first pieces of gear I bought was an E-mu XL-7 Command Station, which my brother gave to me for my birthday a few years ago. It’s an early 2000s rompler; it’s dorky sounding, and dorky looking, but it was an inspiring piece of gear for me to start with. I was listening to a lot of ‘90s trance at the time and I attempted to make a lot of it with the XL-7. (My song “Lift Point” on Route 8’s This Is Our Time was actually the result of the first couple of hours I spent with the XL-7!) I don’t use it as relentlessly as I did back then but I still use it to resample drum sounds and record various LFOed synth sounds. It’s a great tool to turn to if an idea is starting to sound a bit stale because the programmed sounds are interesting.

Since then, I’ve developed my studio and I am feeling like it’s in a great place. At the moment, my setup consists of the following: Ableton 10 on a 13” MacBook Pro; Focusrite Scarlett 4i4 audio interface; Yamaha HS8 monitors; a Behringer MS-1; a Roland TR-8; a Moog DFAM; and the EMU XL-7. I have a ton of digital plug-ins for processing, effects, mixing, and mastering, etc. I’m a big fan of everything from Soundtoys, Fab Filter, Goodhertz, and Valhalla, as well as some of Ableton’s stock plug-ins. I have a couple of synth plug-ins that I consider to be my go-tos: U-he Repro-5, U-he Diva, Tal U-No-LX, Waldorf PPG Wave 2.V, and Audiorealism ABL3.

It’s come to the point now where I feel like I am getting closer to achieving the sound that has been bubbling in my head. It’s a sound that is inspired by hours on dancefloors in New York, Los Angeles, Amsterdam, and Berlin, etc., and by scouring the internet for music. It’s a life-long journey of figuring out the most efficient way to distill an abstract mood, feeling, or sound into music that also works on a dancefloor. For this feature, I’ve outlined the tools that have been integral in helping me to achieve this.

Microtonic is a drum and percussion synth that was released in 2003. It doesn’t use samples or waveforms, but instead consists of eight separate voices, each of which has an oscillator and a noise generator that you can blend. There’s also a sequencer. I’ve always thought it sounds unlike the more traditional drum machines which I’ve become tired of hearing. I’m drawn to punchy, snappy drums, and white noise being used in interesting ways, so I was excited when I stumbled upon it a few years ago. There are a ton of amazing presets that you can build from and there’s a massive library of user-created presets that are all free to use, called the Microtonic Planetarium. This makes it an excellent source of generating ideas, and what’s great is that it has a straightforward interface that allows for precise sound designing for all eight voices.

Pretty much all of the tracks on my Distant Messenger EP have drum sounds from Microtonic, and my track “Tonic” is actually named after this plug-in. I think it was one of the first tracks that popped out when I first started using the plug-in, hence the title. There are some subtle uses of it in my XLR8R+ 030 track “Itchy.” I’ll likely continue to use Microtonic fairly often because it provides me with easy inspiration.

Behringer is paving the way for everyone to have access to affordable analog gear, and this makes me happy. The original Roland gear, back when it was originally released in the ‘80s, was only slightly more expensive than what Behringer is offering now, but because of scarcity it has become too expensive for your average bedroom producer. For a while, it felt like it was impossible to start building a studio with quality synths and drum machines. Now you can have a studio full of all the original gear for the price of an original Juno 106! I don’t believe music-making with gear should be a luxury and I’m glad Behringer allows people to experience the joys of analog synths.

I bought the MS-1 on Reverb.com, which is the easiest place to buy and sell used gear. I’ve used the plug-in version of the Roland SH-101, the Tal Bassline 101, for years but I was missing the playfulness of recording actual knobs and faders. I use it every day for anything from basslines to weird background loops and simple effects. For example, the background bass sound that comes in in my song “Itchy,” starting at 30 seconds, is just a 3/4th bar loop from a four-minute recording of me playing around with the MS-1. Most of the raw recordings I have from the MS-1 are nonsense but I can usually find a small loop that can become the foundation of a song for me to build on which I can then develop. So yeah, it’s such a versatile and powerful synth—you can make some truly crazy stuff with it, and I’ve been having a lot of fun integrating it into my workflow. It’s also a great price, at $300!

Making pads is one of the more frustrating aspects of music-making for me—most of the time I’m trying to go for something light and airy but also full of weird character, movement, noise, resonance, harmonics, etc. The way a pad sounds is important and I usually have to do a fair amount of processing (EQing, adding effects like reverb and overdrive, changing the pitch, etc.) to get it sounding interesting to my ears. I’m also not a traditional musician; I can’t play the piano so I do everything by ear which can take a lot longer. Sometimes I get lucky but a lot of the time trying to nail the melodic portion of a song can take me out of the moment.

Arturia’s CS-80V has been my go-to for pads and general ambience and atmosphere recently. I got an Arturia MIDI controller a while back which came with a free code for Analog Lab—and the more I used the CS-80 section in Analog Lab, the more I realized I needed to just buy the full CS-80, which is a full synth plug-in instead of the limited version I had. The presets sound incredible as well; there’s just a lot of possibility packed into a fairly affordable piece of digital gear. It’s definitely not simple, which goes for the original synth as well, but it allows for happy accidents and sound-sculpting, so I’ll certainly be using the plug-in for many years because it’s such a great, affordable emulation of an extremely expensive and legendary synth.

I spend almost all my my time during the writing process using Ableton’s Session View. I gather various recordings, or “clips,” and I can be as messy as I like. It’s a place to visualize sections of your song before you start to structure it all in Arrangement View. I tend to fill up Session View with different iterations of ideas and sketches of loops which I can then gradually build into a full song. This is the main reason I preferred Ableton to Logic when I was deciding on a DAW. I’ve never been interested in making a song from start to finish; I prefer to focus on building the most energetic section first, then I structure everything around that moment.

Session View is important for my process because it allows me to “zoom in” and experiment in a multitude of ways on each individual element of a song. I find that I become granularly focused on testing out as many possibilities as I can on the various parameters of a loop offered by Session View, like start point, pitch, warp mode, envelope, transient envelope, reverse, etc. Many of my best ideas stem from reimagining stale projects in Session View to reshuffle those parameters on old recordings; it’s like I am remixing myself. I’ve learned that my perception of my own ideas is always changing and just hearing old projects can spark a myriad of new ideas.

One great example of this process is “Doldrums” in this edition. The first version of the song started out as a whimsical, sleepy acid track called “Happy Birthday 303.” The track was always endearing but I think I just grew out of it after a while; it was actually finished and I could’ve released it but something didn’t feel right so I let it collect dust. One day I decided to reopen the project to see if I could either make it sound a bit more to my taste or just take the raw elements and make something completely new from it. For this, I used an Audiorealis plug-in called the Bassline 3 (ABL3). I made the whole thing that afternoon; it was a quick jam with few elements that came together effortlessly.

Typically I do this after I’ve left a project file alone for a couple of months. That means that enough time has passed that I don’t remember what the recordings and individual elements of the song sound like, and this helps me to identify new ideas from a different point of view. I see unfishished projects as opportunities and I try to not get too attached to each song I make for this specific reason; I can usually make something more interesting from the ashes!

My dear friend Gordon Huntley told me about this one. He’s a producer but also does some mixing and mastering work on the side, so he’s clued up on the greatest tools. Smiley by Streaky is a free, one-knob equalizer and audio enhancer effect—making it simple and super helpful! Streaky describes it well: a “smiley face that you can move to add an EQ curve and some other secret sauce to make your mix bus smile a little.” I’ll use this on the master chain of pretty much everything I make. It brightens up the high frequencies, provides a subtle finish to my sound, and boosts the low end. A lot of the times when I’m submitting a pre-master, I’ll keep a slightly happy smiley on my master chain because it just sounds better, which is exactly what I did on both of my XLR8R+ 030 tracks. It can also be an easy fix for taming harsh high frequencies on drums and synths.

Moog DFAM (Drummer From Another Mother)

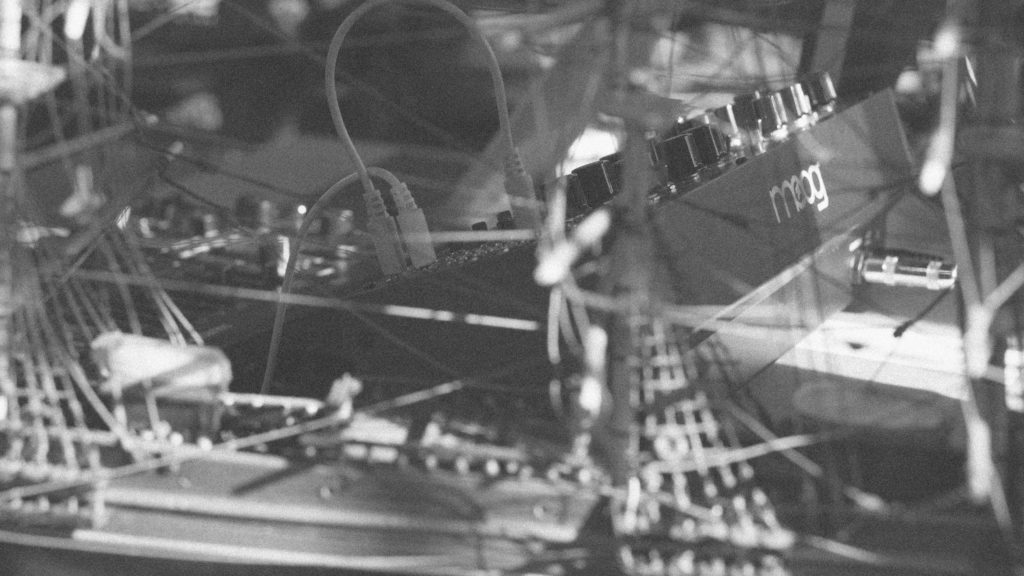

I just bought one of these a few months ago from someone in Alabama. I had a Korg Minilogue XD for a couple of months but I got kind of bored with it. It led to a bunch of new music but I didn’t like the interface and it just had too many features; I actually found it to be more frustrating than fun! So I decided I’d sell it and use the money to buy something new. My brother recently got the full Moog semi-modular trio—DFAM, Subharmonic, and Mother 32. The three of them are incredible and hearing them interact really piqued my interest, but I wasn’t willing to spend the money for all three so I decided the DFAM would be a great place to start.

It’s also a good machine for me because my music is so rhythm-focused. I’ve been trying to strip my stuff back a bit more and give each individual element a bit more care. The DFAM gives you really unique-sounding, tight percussion and you can tweak a lot of the parameters quickly which results in unpredictable, lively percussion loops. It’s a fun toy and I’m excited to spend more time with it. I have it synced up with my Behringer MS-1 right now which is fun for just jamming, at least until there’s an idea I can pursue further in Ableton. As I continue to expand my studio setup, I can see it continuing to provide all sorts of benefits and possibilities because it’s semi-modular.

Time and Space

To me, this is the most essential piece of the puzzle and I’d certainly label it an essential part of my work. If I don’t take breaks and get far away from the music I’m making, I’m unable to enjoy the process. It’s important to get perspective on what you’re creating, otherwise you can lose sight of what it sounds like mix-wise; and if you’re not careful, a good good idea can slip away!

I tend to go on lots of hikes with no headphones to just soak up all the sounds of nature. It’s a helpful contrast to blasting your own music in your ears for a few hours straight. I also often listen to ideas I’ve made while on walks just to see how they sound in a new setting. It’s especially helpful when I’m thinking about the structure of my songs. I try to zone out and pretend I’m dancing to my own music in a club somewhere and this normally prompts a couple of ideas that I can quickly jot down when I’m back in the studio. I’m a firm believer that making music is supposed to be fun and provide you with mental and emotional fulfillment, but it’s so easy to lose this when it becomes a job, which I’ve seen happen to a lot of producers over the years. Anytime I have a moment where I feel frustrated or angry with an idea, I just stop what I’m doing and go for a walk. It works every time!