Trainwreck: David Rodigan Recounts the Shock of His First DJ Gig and the Time He Made a Bad Costume Choice

It’s easy to overuse tags like icon or legend, but when talking about veteran British […]

Trainwreck: David Rodigan Recounts the Shock of His First DJ Gig and the Time He Made a Bad Costume Choice

It’s easy to overuse tags like icon or legend, but when talking about veteran British […]

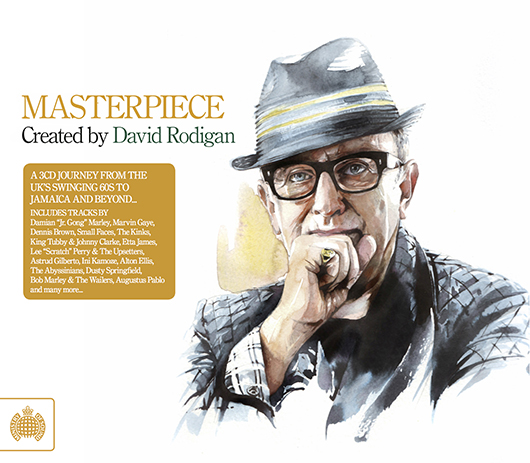

It’s easy to overuse tags like icon or legend, but when talking about veteran British reggae DJ and broadcaster David ‘Ram Jam’ Rodigan, both terms seem appropriate. Since beginning his career as a host on Radio London in the early ’70s, Rodigan has gradually garnered a reputation as one of the most popular and respected names in reggae and dancehall. Over the years, he’s fronted shows on influential radio stations including Kiss, Capital, and the BBC’s 1Xtra and Radio 2, had his voice sampled in tracks by the likes of Breakage and Caspa, and even had his own station in one of the Grand Theft Auto games. Rodigan is also one of the genre’s most prolific DJs, having played to thousands and clashed with some of the biggest soundsystems in the game. Next week, Ministry of Sound will be releasing its latest Masterpiece mix, with Rodigan at the helm. To mark the occasion, we’ve asked the storied selector to take part in our Trainwreck series, and he’s met the request by recounting a couple of the most awkward moments from his DJ career, one involving a misguided jockey outfit and the other a crowd that couldn’t believe its eyes.

The are a couple of nights that stand out for me. My first ever gig in London, in 1979, at the London Apollo Club in Wilsden is one of the most memorable nights of my career. I’d been on Radio London for some time, and I was given my first London booking in a club. I walked on to the stage and the club was full to capacity; I’d been on Radio London for just over a year, so people knew who I was as a broadcaster and knew about my love of reggae music. The MC made the announcement, “Ladies and gentlemen, making his first public appearance, in Wilsden, from BBC Radio London—David Rodigan,” and there was a huge cheer and roar from the crowd. But as soon as I walked to the front of the stage, there was a deafening silence. It descended across the hall in a second—people simply couldn’t believe I was white.

The MC said to me, “You better do something quick.” So I started to speak, and I remember seeing people closing their eyes as I was speaking, trying to picture the voice from the radio. I was quickly ushered over to the DJ box, where I cued up a jingle from my show, which people recognized, and then I played my first song. It was a baptism of fire. Everyone cheered and I got on with the night.

That was one of the most daunting nights of my career as a DJ. There’s another that didn’t end so well, but it’s a little more obscure for people who don’t understand clash culture. In short, clash culture is like a battle of the bands, only it’s the battle of the DJs. The DJs can only play acetates or dubplates that have their name in it, and that have been supplied for them by the recording artist who made the original song.

So I was doing a clash in New York back in the early ’90s, and in those days I would sometimes enter the arena dressed as a character. On this occasion, I entered the soundclash arena dressed as a jockey. The reasoning behind this horse-racing character was because my key card was a dubplate, customized, of [The Pioneers’] “Long Shot Kick De Bucket,” which was a massive British pop chart hit around 1969 or ’70. To put that in context, Long Shot was a horse in Jamaica who was very famous for winning races, who kicked the bucket—died on the racetrack.

So in the one-for-one, which is where you go head-to-head with your opponent, which in this case was Bodyguard Sound System, I cued up and pressed play on this customized dubplate and there was absolutely no response. The audience didn’t know the record; they weren’t aware of it at all and I didn’t get any kind of response at all. So I died a very lonely death in the space of about 90 seconds, dressed as a jockey.

Long Shot was famous in Jamaica, and there are thousands of Jamaicans living in New York, but clearly this was too old a song for them and they were too young to appreciate it—because obviously I’m much older than the average audience. So the metaphorical trap door opened and my fate was sealed: I lost the clash. The jockey character was never to rise again.