Under the Covers: A new Soul Jazz cover-art retrospective traces the visual roots of ’60s free-jazz radicalism.?

Freedom, Rhythm and Sound: Revolutionary Jazz Cover Art 1965-83 (SJR Publishing; hardcover; $39.99), a stunning […]

Under the Covers: A new Soul Jazz cover-art retrospective traces the visual roots of ’60s free-jazz radicalism.?

Freedom, Rhythm and Sound: Revolutionary Jazz Cover Art 1965-83 (SJR Publishing; hardcover; $39.99), a stunning […]

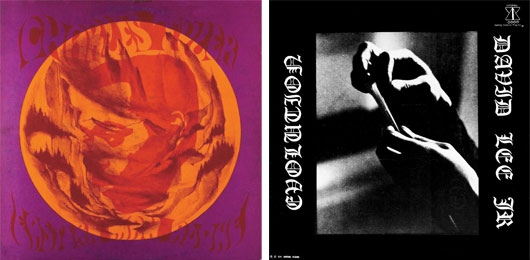

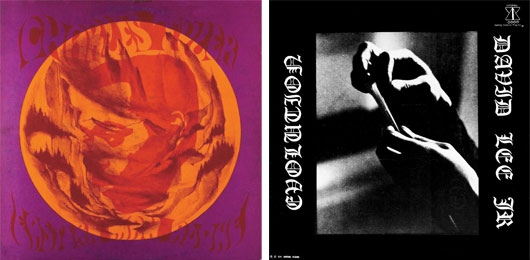

Freedom, Rhythm and Sound: Revolutionary Jazz Cover Art 1965-83 (SJR Publishing; hardcover; $39.99), a stunning retrospective of jazz cover art, is about much more than cool-ass graphics, though, that is undeniably a vast part of its appeal. Curators Stuart Baker and Gilles Peterson trace a potent history of “deep, spiritual, Afrocentric radical artists, and musicians,” pointedly locating their sonic and visual work alongside the actions of momentous political figures such as Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, groundbreaking legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (which prohibited racial segregation in schools, public places, and employment) and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (which outlawed discriminatory voting practices), and even the first manned space mission.

Frequently undocumented, the records of this period present, says Soul Jazz Records founder Baker, “not only a historical archive but also a fascinating display of DIY culture created by a mixture of associations, collectives, individual musicians, and entrepreneurs all determined that their radical music be heard on their own terms.”

On records like Steve Reid’s Odyssey of the Oblong Square and Phil Ranelin’s Vibes from the Tribe, the “outness” of early-’60s free jazz was juxtaposed with the sensibilities of mid-’60s black power and civil rights to forge a radical new music that Peterson now perceives as “as a kind of pre-punk,” with Sun Ra as its Malcolm McLaren figure (though one must wonder if this does the Afro-futurist bandleader a disservice).

Pre-empting punk’s do-it-yourself aesthetic, these short-run records were frequently packaged in naive, starkly monochromatic sleeves (for reasons of economy) with simple, direct typesetting: the African-American Jazz Ensemble packaged their Malcolm X College in a black-and-white snap of the eponymous place of learning; New Life’s Visions of the Third Eye (which is appropriated as the collection’s front cover) deploys a simple-but-effective single color-block graphic; Marcus Belgrave’s Gemini loses nothing for being packaged in the most uncomplicated of etchings.

But what relevance do such sleeves have in 2009? Why publish a book on old jazz cover art now? “I’m not sure,” admits Baker. “I wasn’t conscious of this while we were putting the book together but once I start to analyze it, the election of Barack Obama seems like a final destination in the path of many of the artists of this period. I hope people will use the book to fire their imagination.”

For Peterson, the justification is aesthetic: “It looks so good! In this world of easy downloads with no soul, this book can act as a guide.”

Happily, a companion CD is to follow. “The artwork is a true representation of the music,“ explains Baker. “For me, the best covers do seem to go with the best music.”