Vis-Ed: Konx-om-Pax

Tom Scholefield is feeling a bit rough around the edges. The 27-year-old animator, director, and […]

Vis-Ed: Konx-om-Pax

Tom Scholefield is feeling a bit rough around the edges. The 27-year-old animator, director, and […]

Tom Scholefield is feeling a bit rough around the edges. The 27-year-old animator, director, and audio/visual artist behind the Konx-om-Pax moniker is lounging in the kitchen of his Glasgow home, smoking cigarettes and recovering from a late night. He and some friends organize an old-skool/hardcore-themed party at an old-fashioned lawn-bowling club in the city. It’s six p.m. the next day and and he’s just starting to pull it together. “Last night was the best yet. We don’t advertise that much but we had a really good turnout.”

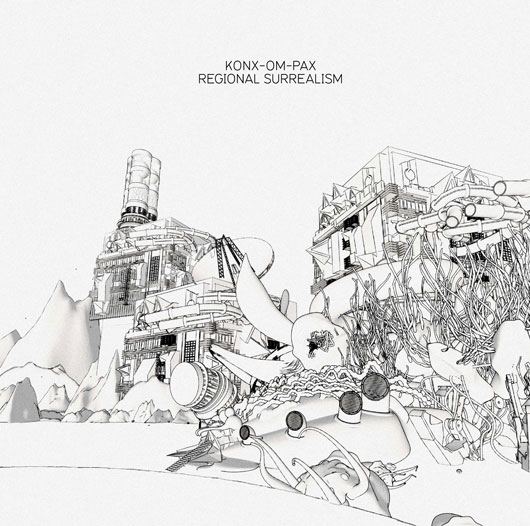

We’re here to talk about his visual work on the eve of his debut album on Planet Mu, Regional Surrealism. The difficulty we experience keeping our conversation focused on the visual side of things is one of many indications that Scholefield’s talent isn’t bound to one medium. He spends a lot of time indoors, making music, DJing, and especially producing the brightly colored, detailed videos and sleeve designs that have become a striking presence in the world of underground electronic music over the past few years. Scholefield/Konx-om-Pax started picking up steam in 2009 with covers for releases by fellow Glaswegians Hudson Mohawke and Rustie (the fluorescent, ’90s bestiary of the former’s Butter and the illustration-software DNA splash of the latter’s Bad Science). Perhaps more notably, he also put together the mysterious virtual-reality obelisk on Oneohtrix Point Never’s No Fun compilation, Rifts.

But his 3-D animations are his most distinctive and technically impressive work. It’s even more striking when you consider the fact that he’s self-taught, and does all the direction and animation on his own. Scholefield graduated from the Glasgow School of Art in 2006, and “ended up doing animation as a way to not to have to do any other studio work.” “I wasn’t too interested in traditional graphic design,” he says of his time at art school. “I was more into sounds and experimental stuff. I remember my tutors putting me on to people like John Cage and Stockhausen, ways to visually represent audio.”

Though his work has made for a coherent story arc in retrospect, Scholefield’s career has been, in his words, “a bit all over the shop.” By the time he graduated from art school, he’d figured out that he didn’t like doing graphics—which is what he studied, in theory anyway. “It was just avoidance,” he of his subsequent move into direction and animation, “but it’s ended up as my main source of income.” Whatever he was avoiding by shifting roles, though, it clearly wasn’t working.

“I spent a lot of months last year just waiting for stuff to render, sleeping in shifts on the sofa in the studio,” he said. “The Martyn video [for Viper] took about a month, and half of that was rendering. I’m a glutton for punishment, but I think of it as learning how to deal with these things yourself so when you get bigger budgets or do more adventurous projects, you can get other people on board.”

Scholefield got his start as a director and animator in 2006, with a visually simple but labor-intensive video for Jamie Lidell. He met the Warp artist through booking shows at the art school. When Lidell, his tour manager, and sound guy needed a place to stay, Scholefield offered his parents’ place in Paisley. “We ended up getting drunk and shooting a video in the garage. We decided we should have Jamie sing a song for my cat,” he said. Scholefield spent the next six months tracing over the frames, a technique called rotoscoping—the process that makes A-ha’s “Take on Me” video or Richard Linklater’s movie A Scanner Darkly look the way they do—to make the two-minute video. The cat looks pretty bummed, but the video introduced him to Warp and opportunities for more work opened up.

Scholefield spent the intervening years teaching himself to craft increasingly detailed, textured 3-D worlds. Despite the accomplishment on display in his most recent piece—the Regional Surrealism album trailer, whose overhead shots of a biomechanical dirigible gliding serenely over a monochromatic landscape call to mind some of late French comic artist Moebius’ iconic illustrations—Scholefield isn’t totally comfortable with the animator title. “I’m technically not as savvy as most people,” he says. “As with most things these days, if you wanna learn about software, you just go online and find every single forum and tutorial. I’ve learned to do videos that way, bit by bit.”

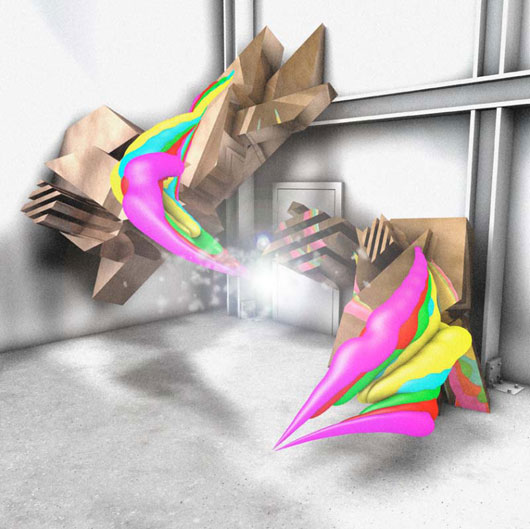

He taught himself the 3-D animation software Cinema 4D on the job, after securing the go-ahead from DFA to make a video for the Capracara track “King of the Witches.” “I did it for free cuz I wanted to practice,” he says. That video is an impressive debut, and like the Moebius nod in his album trailer, it points to another of Scholefield’s influences. The white cubes that spin hypnotically in a bowl take off from Piotr Kamler’s stop-motion animation for the musique concrète composer Bernard Parmegiani’s “Une Mission Ephémère.” But the video also introduces something original, a pace that Scholefield sticks to in many of his animations: it’s a languid, hypnotically measured motion, as if the imaginary camera and all the objects in the immediate environment are submerged in water.

“I watched Solaris the other day and it really fucking freaked me out, man,” he says of a recent aquatic epiphany. The Andrei Tarkovsky film has a few memorable, lingering shots of reeds undulating in clear green water. In the context of the film, these flashbacks stand in for protagonist Kris Kelvin’s nostalgia for the Earth as he bides his time on a scientific research station hovering above a weirdly sentient ocean planet. In Scholefield’s own work, the earthly and unearthly coexist in the same space. As fantastic as Konx-om-Pax videos are, they’re still tied to the physical world. “I love quite dark sci-fi, and I’m really fascinated with water and reflections. I started thinking about how that relates to the idea of alternate realities and different states of being, joining the dots between Drexciyan mythology and a Tarkovsky film.”

Some of his most important influences come from the highbrow, avant-garde side of things, though retro sci-fi references are equally important to his work and float closer to the surface. He’s far from alone in this kind of cultural salvage work, the willful flattening and defamiliarization of familiar points of reference. Think of Oneohtrix Point Never’s Daniel Lopatin and his YouTube “echo jams,” or the Windows 95 dystopia of James Ferraro’s polarizing Far Side Virtual. Scholefield talks of his affinity with “your average Brooklyn synth dude.” So when he describes James Ferraro as a “total dude, really into stuff,” his vague specificity suggests it’s a particularly apt self-description as well—Scholefield seems to bounce between esoteric and pop-culture references in conversation and in his work, but for him, there’s no distance. His cultural omnivorousness finds expression in his portfolio as well, blurring the line between reverent homage and futurist impulses. He’s done graphic design for and toured as a DJ with post-rock figureheads Mogwai on the one hand and made neon sea anemones dance in the video for Hudson Mohawke’s “Joy Fantastic” on the other. The music he makes as Konx-om-Pax is insular, foreboding, and monochromatic, while the art he contributed to Lone’s 2012 album Galaxy Garden is as alien-bright as the neo-rave tunes inside. Indeed, Glasgow seems to have a pronounced interdisciplinary vibe, abetting people like Scholefield who seem to draw energy from variety.

“Everybody does everything,” he says of Glasgow’s vibe. “There are loads of tiny scenes, it’s all sort of intertwined. My favorite club nights are the ones with music policies like Numbers‘. You can go and hear old disco, then it will go into crunk and then into Drexciya. It’s all over the shop. It’s the same thing with Optimo. Good, solid eclectic things.”

Conversational detours from Scholefield’s own work into topics like Nam June Paik and getting sucked into UbuWeb’s avant-garde rabbit-hole are par for the course for a “total dude, really into stuff.” But the contours of the discussion also establish that, in a generationally appropriate way, Konx-om-Pax is truly a catchall banner for all of Scholefield’s activities. For him, as for his viewers and listeners, there’s no hard and fast distinction between creating and taking in, much less being a visual artist and an audio artist. He takes turns playing each ostensibly distinct role. Regional Surrealism, for example, took shape in the wake of an “animation headfuck,” a disillusioning experience working with a production company and label last year. “I started making music to sort my head out from all the crap associated with doing animation, it was quite the fix,” he says.

But now that the album and its trailer are in the can, he’ll be going to go back to directing videos for other musicians. He’ll be shooting a video for John Cale in the near future, but for now, he’s just going to chill and watch some TV. Must be nice to use a sofa for something other than sleeping during marathon rendering sessions.