War Inna Babylon

Most Jamaicans can’t be bothered with the War on Terror, but the music tells another […]

War Inna Babylon

Most Jamaicans can’t be bothered with the War on Terror, but the music tells another […]

Most Jamaicans can’t be bothered with the War on Terror, but the music tells another story.

When the US invaded Iraq, I was living in Kingston, doing research for my dissertation. As I waited for a bus on Hope Road, a man biked past me and sneered “Bloodclaat American!” Similarly stereotyped, people of Middle Eastern descent in Jamaica became popularly referred to as “Taliban,” as in Elephant Man’s matter-of-fact address “whether you a baldhead or a Taliban.” Ele delivers the line over the Coolie Danceriddim, partaking in the same discourse about the Middle East as the American media and further reinforcing differences between the West and the rest.

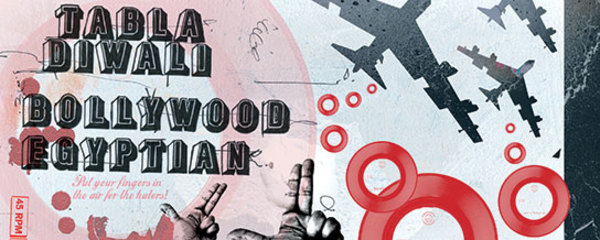

The Coolie Dance is one of many “orientalist” riddims that have mashed up the dance in the last few years; others include Tabla, Diwali, Bollywood, Egyptian, Amharic, Sign, Baghdad, Allo Allo, and Middle East. Partly inspired by a parallel trend in US hip-hop (“Get Ur Freak On,” “React,” “Addictive”), partly from a longstanding tradition of Jamaica’s own fascination with the East (“Eastern Standard Time,” “East of the River Nile,” “’Til I’m Laid To Rest”), and partly enabled by the tabla patches and “Indian flutes” available on the studio-standard Korg Triton, Jamaican producers and DJs have been responding to the Bush administration’s War on Terror in myriad ways. One hears everything from explicit anti-war songs–Capleton’s “Baghdad” and Luciano’s “For the Leaders”–to tracks that incorporate references to the war in a subtler manner. Vybz Kartel’s compliment to a Jamaican woman in “Stress Free”–“Skin smooth, e? You a wha? Barbie doll?/You nuh haffi hide your face like Bin Laden gal”–expresses a preference for a Western sense of beauty and a willingness to trade in stereotypes of Muslim women.

Whether or not Kartel intends it, such sentiments reinforce neo-conservative ideologies of “freedom” and universal–which is to say, unilateral–rights. American ideologies circulate globally via American music, including music once considered oppositional (such as hip-hop). These ideologies are then partly reproduced, partly resisted, and newly articulated through the lens of Jamaican culture.

When people talk of war in Jamaica, they usually mean the gun battles that routinely erupt in downtown Kingston, and the “gun hand” in the air remains the most common form of audience approval. If war can be found right down the road, why worry about some fanciful American crusade abroad?

In a comedy routine I heard in Kingston during the spring of 2003, a redneck-accented George W. asked Prime Minister P.J. Patterson if he could commit some troops to the “coalition of the willing.” P.J. responded, “We don’t have enough troops to fight a war with Tivoli.” The crowd roared. For them, Jamaica’s internal war–symbolized by the reference to Tivoli Gardens, longtime stronghold of the JLP, the opposition party to Patterson’s PNP–clearly presents a more urgent problem than “bringing democracy to the Middle East.”

Even so, Jamaicans feel the effects of the War on Terror, and reggae has registered much of this anxiety. “The Bombing” is one of the more eloquent reflections on 9/11 and its aftermath. Not only does Elephant Man come up with a coup of a couplet, rhyming “Bin Laden” with “cannot be forgotten,” he notes that “Visa a get deny through the bombing,” calling attention to one salient consequence of 9/11 for many Jamaicans: further restriction of mobility.

In contemporary dancehall videos, sampled news footage of Falluja gunfights, bombed-out buildings, and morbid scenes from Abu Ghraib fit perhaps too easily alongside images of downtown Kingston. The “Jamaican street” remains as hostile toward the American government as ever, but the dancehall massive is “still jammin’,” according to Elephant Man: “Down in Jamaica, yes, fun we still havin’/All of we dancehall dem keep on rammin’/Gal a do hair, fingernail, and shopping…music lick on, champagne still popping.”

Wayne Marshall is an ethnomusicologist working on an intertwined history of reggae and hip-hop.