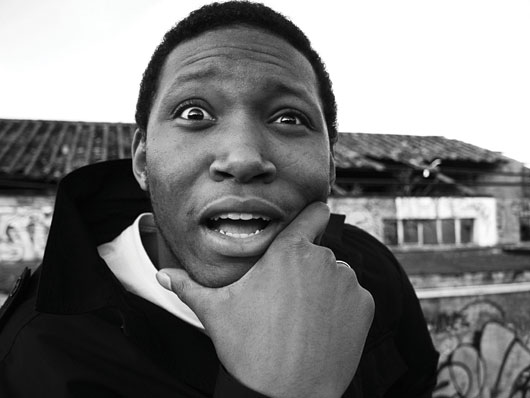

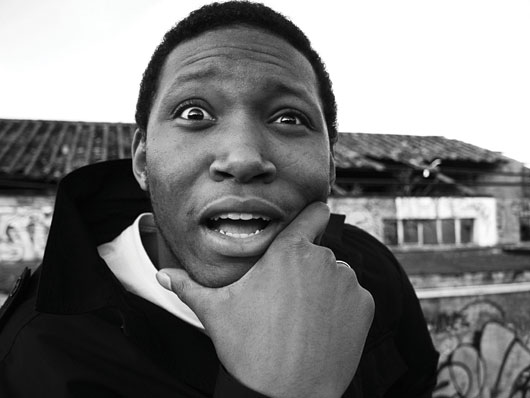

XLR8R’s Favorites of 2009: Joker

With his growing reputation—and the promise of a debut full-length—Bristol’s Joker takes it one day […]

XLR8R’s Favorites of 2009: Joker

With his growing reputation—and the promise of a debut full-length—Bristol’s Joker takes it one day […]

With his growing reputation—and the promise of a debut full-length—Bristol’s Joker takes it one day at a time.

Months before he’ll complete his debut album and probably longer until it will reach listeners, Liam McLean is holed up in his home studio, stressed. A string of thrilling singles has branded the 20-year-old Bristolian, known as Joker, dubstep’s next great producer, and the pressure that accompanies that title is clearly wearing on him. Mostly, though, he just misses his bicycle. “I used to ride my bike a lot,” he says. “Do dirt-jumping and stuff. But within the past few months, things have gotten hectic and I haven’t ridden my bike for ages. Couldn’t say the last time I’ve been on it. I’m just stuck in my room or stuck in a club or stuck on a plane. I’m pretty mind-rocked.”

That might seem like an odd complaint for a guy who seems to have the world at his fingertips, but Joker isn’t your average artist. With a shyness that borders on the defiant, he is, like Brian Wilson or Burial before him, a studio rat with perfectionist tendencies (and very possibly a genius streak), the kind of dude who prefers quietly making beats in his bedroom to just about anything else. He likes movies and cooking, and isn’t too thrilled about playing live sets (“Right now it pays the bills,” he tells us). So how did Joker come to be seen as the man to possibly redefine dubstep and help carve out a new subgenre—wonky—in the process? First, remember that he’s been making tunes since he was 14.

Joker came up in Bristol, the culture-rich port city in Southwest England—home to such greats as Robert Wyatt, Portishead, and Massive Attack—where he still resides today. Feasting on a healthy diet of grime and garage at a young age, Joker joined a hip-hop crew as its resident DJ around 14 and quickly saw an opening for his burgeoning production skills. “I seen them start to make tunes and I thought, ‘If I’m going to be the DJ for them, I could, like, be the producer as well,’” he says. “So that’s kind of when it started.” But even then, Joker felt like there was something missing in the records he was buying and spinning—an opening for him to inject his own style. “I would get to a certain bit [of a track] and wish that things would go on a bit longer or have extra sounds I’d never heard,” he says.

Eventually that urge to hear fuller and more exciting sounds would result in the creation of Joker’s own material, and a stunning series of 12’’s that combined modern dubstep with Nintendo blip, ’80s funk, and ’90s hip-hop. Singles trickled out over a few years, beginning with 2007’s “Stuck in the System,” notable for its crisp melodies and marriage of grimy low-end wallop with lush orchestration, and “Snake Eater,” which ran videogame samples through Neptunes bounce. The tracks dovetailed with the rise of similar sounds in the UK and abroad—a thread can be woven through the work of Glasgow’s Hudson Mohawke and Rustie, as well as Hyperdub’s Darkstar—which prompted UK journalist (and occasional XLR8R scribe) Martin Clark to name the budding movement “wonky,” characterizing its mid-range as “being hijacked by off-kilter, unstable synths.” Meanwhile, Joker’s cuts were growing stronger and more singular with each release, but it wasn’t until recently that folks outside Bristol began to take notice of his prodigious talent.

?

If there are two tracks that put Joker on the international map, they are “Purple City” (a collaboration with pal James “Ginz” Ginzburg) and “Digidesign,” both released this year on Joker’s Kapsize imprint and Hyperdub, respectively. Alongside Joy Orbison’s ebullient “Hyph Mngo,” they represent the most exhilarating dubstep-affiliated tracks of 2009, and though traces of their parent genre remain, the songs ultimately represent a new brand of future-pop that seems equally suitable for the clubs as it does headphones. “It’s sort of like dubstep meets hip-hop meets R&B meets grime meets funk, if that makes sense,” Joker says of his own work. Part of the appeal of the material is inscrutable—the way he’s able to twist and bend synth lines into compelling melodies—but part of it is simple structure: He likes a good hook. “I just can’t stand shit that sounds like one tone; it doesn’t bring you nowhere,” he says. The other component is his commitment to using what he calls “real” equipment, namely hardware over software.

?

“I used to make my tunes in Reason,” he explains. “But when I listened to, like, more established music in the scene, there was a big difference in quality in how wide the sound was—just sonically massive. There was a certain point in Reason that it just wouldn’t go past. I think that’s where you have to come out of the computer.” It’s not about what you can’t do with software, Joker says, but that there’s a higher quality of sound he’s able to achieve with physical equipment. “For instance, if I have to get a sine wave with a square wave on top of it, just for, like, a simple bass, the difference between that coming from a hardware and a software would just sound completely different,” he explains. But even if he’s been able to refine the nuts and bolts of song creation, that doesn’t mean tracks like “Digidesign” come easy.

Joker’s “Digidesign”

And, of course, there’s that album to think about. “I’ve been working on it every day but I’m going to stop that now,” says Joker. “It kind of puts me in a certain working mode where I’m trying too hard. So I’m just going to relax and make beats as normal and then figure out the album when I’ve got a certain amount of tracks together.” But that might be easier said than done. There’s a note of exasperation in his voice when he talks about the record, and with a busy touring schedule and more than a few remix commissions on the table, time is short. “There’s just no time for rest,” he says. And part of the weight of expectation, it seems, is self-imposed. He turns to his computer to check the status of the as-yet-untitled LP. “I’ve got a folder called ‘Album’ and there are 119 files in that folder. I probably like one of them.”

With that kind of quality control, one gets the sense that the Joker full-length could very well exceed expectations; it’s just a matter of getting there. Joker knows what he wants it to sound like but won’t give away too much (“I’m not good at explaining tunes, definitely not my own tunes,” he says). He knows he wants it to be a capital-A album. “I want it to be very listenable instead of just straight tear-up-the-clubs kind of shit. With, like, a beginning, middle, and end—you can listen to it all the way through.” In the meantime, though, he’s simply looking for equilibrium between the life offered to him by dubstep superstardom and his much quieter one in Bristol. “It’s a sacrifice,” he says. “I’m still trying to find the right balance of me being okay and doing the things I want to with music.”