In the Studio: Surgeon

When it comes to techno, Anthony Child commands a level of respect that few artists […]

When it comes to techno, Anthony Child commands a level of respect that few artists can match. Since moving to Birmingham in the late ’80s, he’s released records as Surgeon via esteemed labels like Downwards, Tresor, and Blueprint, though he most recently issued his first solo record in over three years through Belgian imprint Token. This, coupled with the announcement of a six-part reissue series compiling some of his early material from old DAT tapes, got us thinking about the time in between and how Child has managed to keep his studio an exciting place throughout a 20-year career. Having recently been experimenting with a new modular set-up, the UK producer was more than happy to share some of the ups and downs he’s experienced along the way, and during the course of our conversation, he also touched upon the art of live performance and the importance of taking on new challenges.

XLR8R: A good place to start, since you’ve recently announced the SRX series, is at the beginning. What was your studio like around that time?

Anthony Child: When I first started making music, it was purely with hardware because I didn’t have a computer at the time. I basically used whatever equipment I could get my hands on, so it was very basic. And quite frustrating at times as well, because the equipment was not really very good. But looking back now, I look at it in a very different way and I realize the good things about that, in the way that it forced me to be inventive and creative in the way that I used those machines. And it’s a story that repeats many times about people starting off with bad gear, or using it in a way it wasn’t really intended because they didn’t have a choice. So that’s very much the way that I started making music—having to force something out of bad machines, if that makes any sense.

There’s a great quote from you about how when you first began releasing music, the engineer actually had to leave the room while your record was being cut because no one understood electronic music. Where were you looking for advice at the time then, in regards to what you needed for your studio?

Well, I actually moved to Birmingham in 1989 to study sound engineering at a technical college, and that was really good because I got to use a lot of studio gear that I never would have been able to touch because it was so expensive. You know, the mixing desks and the 16-track tape recorders and outboard gear and stuff like that, plus a few friends pulling any keyboards or drum machines or mixing desks together to create a very basic kind of studio and just creating in that really. And that was kind of the first period of making music, and that’s when the first music came out on Downwards and Soma.

So many people are referencing that early Downwards style as a source of inspiration at the moment. How do you keep the process enjoyable for yourself after so many years? How do you keep a sound interesting for yourself?

I’ve experimented with different approaches over these 20 years, but when I kind of strip it back to the most fundamental idea, the most important thing is to make very, very honest music. That’s the most important thing—I don’t want the music to pretend to be something it isn’t. I don’t want to con people. I feel like putting music out there as purely and honestly as I can is the best thing I can do. It’s the best gift that I can give to people who listen to it, and buy it, and dance to it, or whatever. Whether they like it or not is completely up to them and it’s got nothing to do with me, but if I put it out there and it’s as honest as I can be, then that’s the best thing I can do, really, and everything just kind of builds from that. So for me, that’s like stripping it back to its essence. And it’s got nothing to do with its style, if it’s heavy or light or melodic or atonal, it’s just about very honest and pure expression.

Talking about honest and pure expression, how do you manage to make that work?

I think that every technical approach to making music has its advantages and disadvantages, and it also depends on when that technique comes along in your creative life. So different things work better at different times. For quite a long time, I felt quite stuck with making music in the software realm. So if I actually kind of rewind a bit to make sense of that—I was talking about making music with this borrowed, very basic equipment, and this is going back 20 years ago. Then I signed a deal with Tresor and I actually got some advance money that allowed me to buy my own gear. That really changed things, because I got to choose what I made the music with. And that worked out well—I bought a computer eventually and started working with Logic Audio and Ableton, so my production gradually headed further into the software realm. And at times that was very liberating, because the ideas I had I was able to translate more effectively, and it was really liberating, initially. But staying in that realm for a long time, I began to realize that restrictions were actually a good thing and forced you to find creative solutions. I was really looking for a way of getting myself back on track.

So when you were immersing yourself in software, did you keep hold of your equipment?

I haven’t got rid of any of my equipment. Not all of it still works, and sometimes a power pack might blow up and it’s completely impossible to replace, and DAT players get jammed, but I’ve kept everything. So more recently, I’ve been dragging a lot of that gear out again and having a lot of fun with it.

And you’ve been in this space for how long?

It’s in the same place it’s been for about 10 years now.

Was it straight after reaching this point of frustration with software that you introduced the modular?

It was just seeing more people playing with that stuff, and initially I wasn’t really… I encountered modular synthesis quite a long time ago, but I wasn’t really that interested in it because it seemed like you had to spend thousands of pounds to make a very basic kind of ‘clip-clop’ sound, and that didn’t really appeal to me.

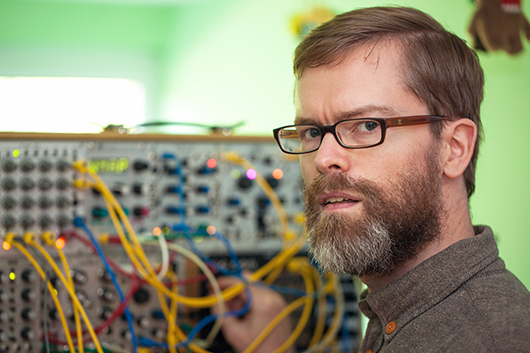

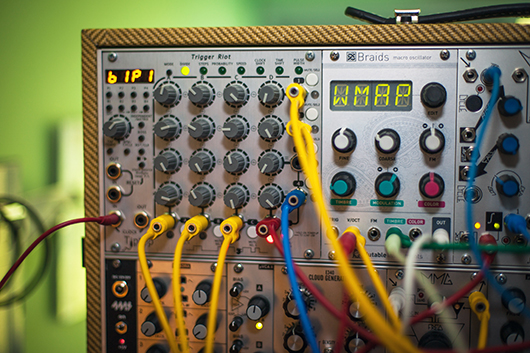

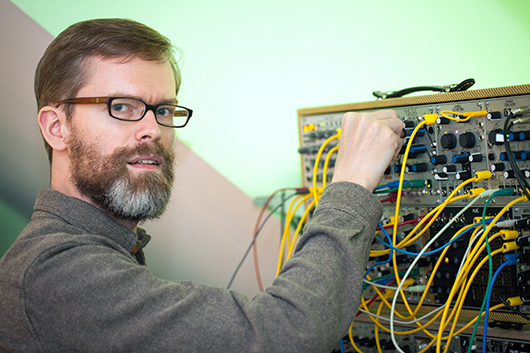

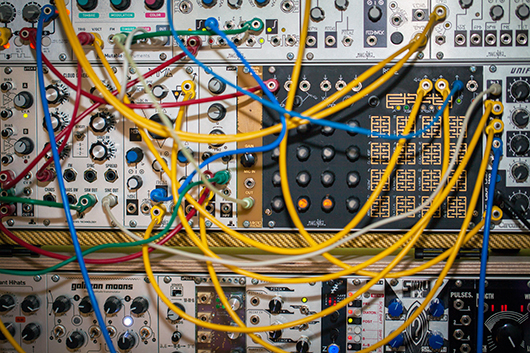

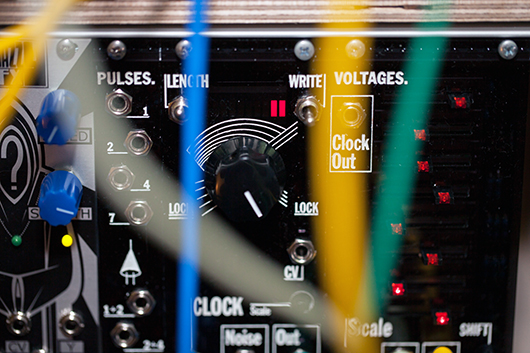

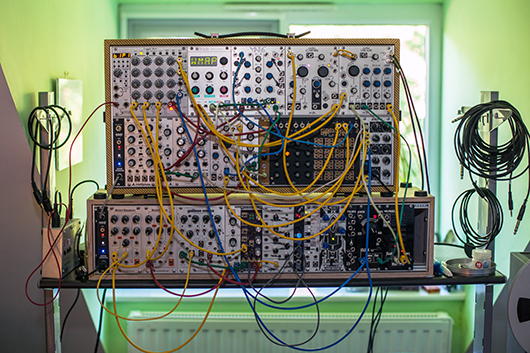

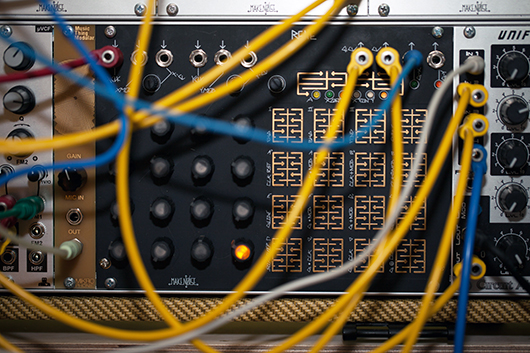

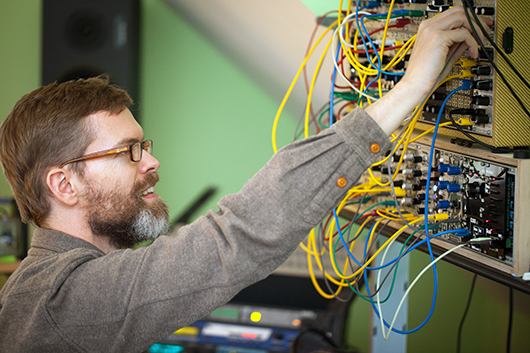

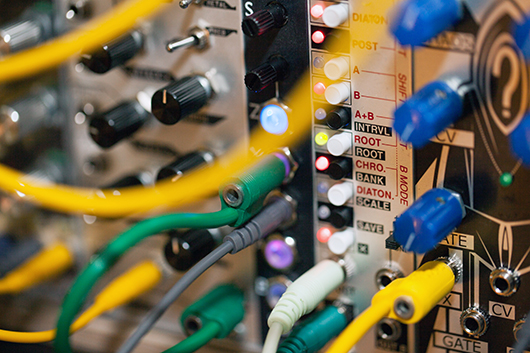

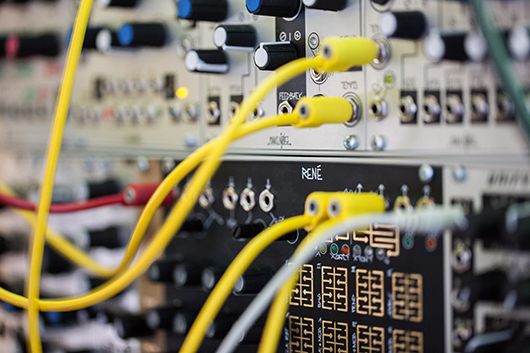

But [now ,] it’s really connecting with a younger generation of producers and [I enjoyed] seeing how much fun Jamie [Roberts (a.k.a. Blawan)] was having, because he and I do gigs together and I was confounded at his box of wires. But it just looked like a whole lot of fun, and that’s kind of what I was looking for, I think. Fun and play are very important aspects in music to me, so I just started playing around with getting into it—loads of Make Noise and Intellijel modules, Basimilus Iteritas and Zularic Repetitor from Noise Engineering, a bizarre random sequencer called the Turing Machine—and it’s just been really good fun, and quite a different character in the studio. It balances out really well with the computer and the old gear. It’s a real wild animal.

Blawan has talked about how he records big chunks of audio and then goes back and edits it afterwards. Are you working in the same manner? Are you using sampling techniques alongside it?

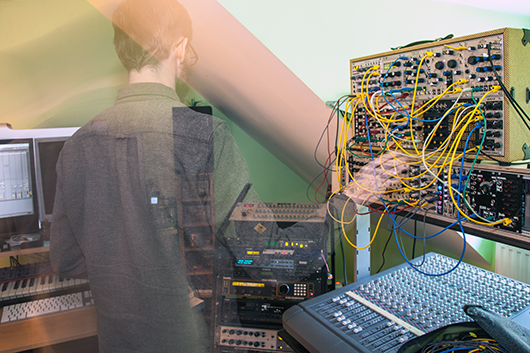

Yeah, sometimes. A set-up that has been working really, really well is to basically take different outputs from the modular, so from each sound-producing module and effects and whatever. Take separate outputs from those and go to the mixing desk and then take the direct out from the mixing desk into the MOTU sound card, and basically use Ableton as a multi-track recorder. So I can record the jam, but I’m recording each separate aspect of it. And that way, I can mix it again or I can take separate parts of it, stuff like that. I found that a really good way of recording stuff with the modular, and I can keep it as it is or I can pull it apart.

And what outboard equipment would you use to process those individual stems?

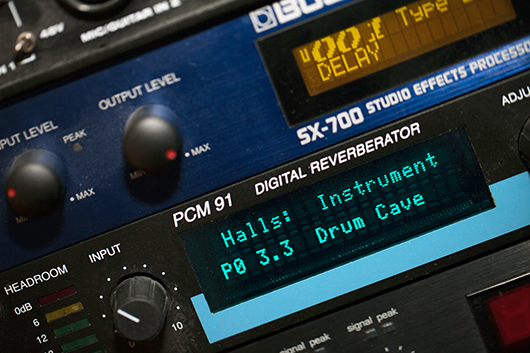

The outboard gear I’m using when I mix the separate recordings from the modular is mainly a Lexicon PCM91, a Boss SX-700, an Eventide H3000 D/SE, an LA Audio Classic Compressor II, and a Focusrite Platinum Compounder.

Ableton is still an important part of your studio. How much of a creative tool is it, as well as a recording device?

Well, for a very long time it has been the key thing in the studio, really, and I have done a lot of music purely inside Ableton and working with a lot of audio, but not using a huge amount of other software and hardware. Quite often, I find it good to bring the separate outputs from Ableton through the MOTU into the mixing desk, to mix it again, and it does give it a different kind of quality rather than just keeping it all mixed and rendered in the software. I have done a lot of projects purely with Ableton, but during the 20 years that I’ve been releasing techno, I’ve really found it very important to not get too comfortable with the method and the set-up that I use, and I’ve found that many times where, if the method gets too comfortable, if it doesn’t really challenge me or push me, it’s time to change it.

In the same interview with Blawan, he was talking about how he was using Ableton and then felt like he’d mastered it, somewhat, and it was time for a change. Do you feel like with your modular set-up at the moment then, taking it on the road with you, you’re challenging yourself? It’s quite unpredictable.

Yeah. Similar to what you mentioned Jamie had said, I felt much more [like it was time for a change] in the performance side of things. I still call it DJing; I was using Ableton and it was working really well, and I was able to have very effective and precise control over the way the music worked, and the effect it had on the audience. And [I was able] to really control, very precisely, the energy of a DJ set. But it was starting to get too comfortable, and not really so challenging, so combining a modular set-up with that, it’s such a different character, sonically and—it’s like throwing a wild animal into the equation. It just works so well, because it sounds so different from Ableton. And the sounds don’t get in the way of each other, because it sounds so different. And when you play it over a soundsystem combined with Ableton, it sounds so fantastic, and they really fill in each other’s gaps with their strengths and weaknesses.

I’ve been doing that since late June I think. I just took it along for one gig, just to try it out, and I knew straight away there’s no way I’m going to go back to just playing with Ableton, because it’s just so much fun. It’s effectively improvising live over the tops of the tracks that I’m DJing. It’s really, really good fun, and the reaction from the people has been really good. I’ve noticed that even when they can’t see the modular, they react very strongly because the sound from the modular is so direct. They can really sense that it’s something that’s being created right there in that moment. And it creates something that’s very, very different from playing back a recording, whether that’s with Ableton or with vinyl or whatever format. I think it’s a really different effect that it has—it’s very powerful and really, really exciting.

This sort of hybrid—I mean, you still say it’s a DJ set, but it’s sort of evolved now, having all of these improvisational passages. Would you ever consider doing a completely improvised live set?

Well, that’s basically what Jamie and I are doing with Trade now. We’ve been doing Trade gigs for a year now. I think we’ve done six, maybe seven. And technically, the set-up we use, it’s changed a lot. Currently it’s both of us just purely with modular, so we’re not using any computers or sampling. It’s very raw and very direct. Nothing is prepared because you can’t prepare anything, really, except maybe a patch that you’ve made. It’s really exciting because of that, but it’s totally like hanging on to a cliff with your fingertips. It seems to work and it’s very exciting and very raw, but I think it works because there are two of us, and it allows you to fill in for each other and have a bit of a breather. Doing a pure modular [myself]—maybe one day, but it’s a bit nerve wracking alone. I think it’s very different if you start to add stuff like drum machines into the equation.

You’ve got a 909 in your studio. Have you ever brought that out with you?

I haven’t done it yet. I’ve got some ideas about something that I would present as a live set that would involve modular and some other bits of hardware, and other parts using Ableton, but that’s just something I’m working on at the moment. I haven’t quite settled on exactly what the set-up is. I’m certainly not abandoning Ableton, it’s just serving a slightly different role in the equation. When I first started using a computer, I was using Logic Audio, and it was so much about menus—and I really hate menus, diving through menus to find things. I started using a very early version of Ableton; it was version 2, or something, and as the program grew and got more complex, I was still using it, so I saw it grow very gradually and I’m very comfortable with it. I still feel that’s my digital audio work station of choice, but it’s serving a slightly different function in my studio now.

With you utilizing this live set-up in the studio, and focusing less on structuring a track, is the end goal still to make records, or are you just concentrating on having fun with the creative process?

All the different factors shift around in their significance and importance, and right now play and fun has really come back again. Because sitting in your studio in front of your computer monitor is not a fun state to be in at all. I’ve always said that I don’t want to release something if I don’t feel I have something to say. And an important thing to me is not having a release schedule that I hold myself to. And a lot of the time, I feel really satisfied musically from the DJ performances.

And you’re not in a rush to head to the studio to recreate them, or embellish recordings?

I enjoy the transient nature of DJ performances, and having a recording is such a tiny part of the whole equation of what could make that night really special. Back to the beginning of when we were talking, it’s very hard to sum up 20 years, because my ideas have changed a lot and have been all over the place during that time, and I’ve explored different approaches and ideas.

It’s funny how many people come back with a similar story about how when they were first starting out, they were incredibly limited, and then they got into the digital age and realized that those limitations were actually what was most inspiring to them, and so their approach has almost gone full circle.

I can definitely see that that’s kind of a common story. And I feel I’m in much more of a liberated situation at the moment, and not so stuck really. And that’s definitely a good feeling in terms of the music and performance.

Is it this liberation that’s lead to your recent ambient sets?

Yeah, maybe. The ambient sets, they’re really connected to and expressing something that’s very, very personal to me because that type of music—when you’re talking about people like Coil, and those types of bands—that electronic music, I still love that. But it’s the music that I originally followed, way before I was ever aware of techno, or before techno even existed I guess, because I’ve been following music like that since the mid ’80s. So it’s a much deeper and more personal type of music for me. And of course I recognize that I can’t turn up at a big rave in Amsterdam and play that type of stuff, because it’s not really going to work. But there have been situations, like at Freerotation and Labyrinth, where the situation has been right for that kind of music and people have asked me to do that.

So it’s actually been something you wanted to do for a while, but you never really had the platform to do it.

Yeah, it’s always been a real personal interest for me because I listen to and follow that kind of music, but there’s not often a performance situation that’s appropriate. I guess it also depends on how currently popular that style of music is as well.

Talking of new challenges and inspirations, what’s next for you? Is there anything you’re currently looking to obtain for the studio?

I think with my current situation in the studio and with performing, I’ve really only just begun a very new chapter, in terms of bringing back hardware into the equation, getting into the modular thing—that’s a whole world on its own. So right now, it’s very inspiring, exciting, and fun. But I’m always trying to keep perspective and to not just get lost down this rabbit hole… It’s this kind of wormhole that you could fall down, and you could just sit there and wiggle away, and never ever record anything or make music because you just get lost in this modular world. So again, it’s having perspective and the discipline to say, “All right, I’m going to give myself a task and go through with it,” instead of getting lost.