In the Studio: Health—The LA noise rockers ponder predatory beats and subvert their engineer’s advice.

On its latest disc, Los Angeles-based, EFX pedal-saturated quartet HEALTH presents a sprawling feedback loop […]

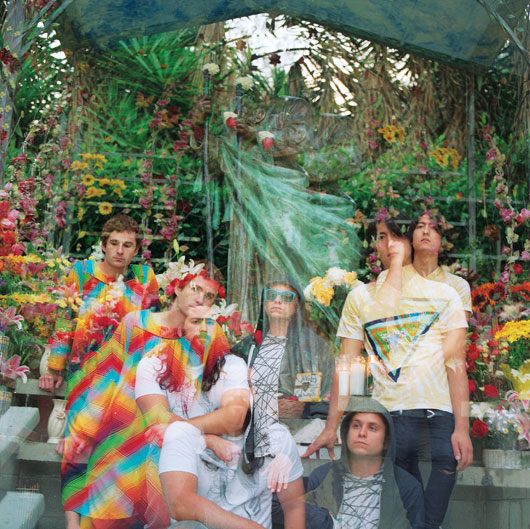

On its latest disc, Los Angeles-based, EFX pedal-saturated quartet HEALTH presents a sprawling feedback loop both manically chaotic and meticulously paced. Featuring drummer Benjamin Jared Miller, singer/guitarist Jake Duzsik, bassist John Famiglietti, and guitarist Jupiter Keyes, HEALTH has followed 2007’s self-titled full-length debut with Get Color, an album borne from a sweltering, windowless practice space, an opening slot on the Nine Inch Nails tour, Tecate, borrowed Mesa Boogie amps, and gently nuzzling a good ribbon mic. While taping contact mics to floating looms and broken elevators, HEALTH painstakingly adjusted knobs and randomly generated harmonics to compose their most accessible, uncompromised tracks. Here, Keyes and Famiglietti hint at how the band ultimately arrived at its scorched grooves and cross-bled melodies.

Tell me about your recording environment.

Jupiter Keyes: We found a studio in Lincoln Heights with 30-foot-high walls that was 30 feet wide and 50 feet deep. It was drywall, though, while we were hoping for concrete or adobe or brick because it diffuses the reverberation a bit better than a flat surface. But it was still a very, very different experience than the first album, which we recorded in [downtown Los Angeles D.I.Y. performance space] The Smell.

What is it that the engineer provided?

JF: The first album, we didn’t know what we were doing; it was made mostly on laptops with whatever gear we had.

?JK: On our first album, John went to so many message boards and then we applied whatever knowledge he could find. That might lead to six hours moving a mic to get it to sound right. So working with an engineer, we learned so much about things like phase cancellation when layering, properly positioned monitoring to really understand how your bass resonates—things that are important when recording.

Once you had that knowledge, did you prefer to use or abuse it?

JF: From our point of view, I would say use, but from the “proper” point of view, it’s definitely abusing.

?

JK: There were near-yelling matches; the engineer is a purist and we wanted to not be so by-the-book, even if it’s problematic… For example, mixing to a two-track, we wanted to use the boards to make a more rich pan across the stereo spectrum, but he’d say the pots are too scratchy or whatever rather than saying he didn’t want to do it because it’s not “right.” But sonically it was what we wanted, so that had to be stuff we’d attempt to do later on our computers.

Are the sounds predators or prey? Are they being chased or chasing things??

JF: I would say the sounds are prey. We try to control and repeat everything we do. When we create, whatever noise we add, we rein it in to a response we can use.

?JK: But every once in a while, there’s a jaguar on the tree branch, a surprise that hits us.

?JF: One jaguar that almost killed us was there’s this shitload of fucking crackle caused by faulty studio equipment. But at the same time, there was a lot utilized from these jams that was used for noises later. That’s where a random flash gets in, something you can’t repeat that’s for the record only.

Did this album ever feel like going against instinct in a way that was refreshing?

JF: With technical stuff we were all for it, but when it came to other things that seemed overly conservative, that was a big bummer. For certain things we had to remix more on our own later because we wanted to use sub-bass, but it was contrary to the engineer’s sensibilities.

Why sub-bass?

JF: It’s just something that separates modern music from older records. Sub-bass is a way to translate that feeling of experiencing someone live… through your ears and also through your body.

When did the process feel complete?

JK: I would say when we scrapped a lot and did it ourselves.

?JF: We didn’t want to mix on Jupiter’s laptop—it sounded much better on the studio gear—but some things got so messed up. So then our mastering guy filled in the blanks.

?

JK: He took the tracks and added grit and warmth to make the laptop sound like the studio. We used Logic for the [remix], to add the sub-bass, and I had some Yamaha HS50s and a subwoofer for monitoring, so that helped fill in a lot of shit.

Is there anything you enjoy about all the chaos?

JF: We love the feeling of chaos, but not actual chaos… that isn’t gratifying.

?JK: Our music is about creating the illusion of chaos, like everything is about to fly off the edge… but it’s all premeditated.

?

SIDEBAR

Pedal Files: A Healthy Helping of the Boys’ Gear Collection

In the main “studio”

• A 25-year-old-plus Neotek Console for adding aggressive edge to analog tape

• A tiny 50-year-old-plus, grenade box-like solid state amp originally used for dialog/effects playback on movie sets; great for close miking

• Logic 8 on a MacBook, for mixing and to isolate and add sub-bass to keyboards

• Yamaha HS50 monitors and HW10 subwoofer

Jake Duzsik

• Electro-Harmonix polyphonic octave generator

• DOD 250 overdrive preamp

• DigiTech RP300 pedal

• Foxrox Captain Coconut pedal box

• Maxon PH-350 rotary phaser

Jupiter Keyes

• ZVex Fuzz Factory pedal

• Line 6 DL4 pedal

• DOD FX75-B stereo flanger

• Moogerfooger MF-105 MuRF (“Multiple Resonance Filter Array”) effect pedal

• Behringer UP100 two-mode phaser

• Korg 707 FM synthesizer

• Dunlop Dimebag Darrell Signature wah pedal

John Famiglietti

• Boss RC-2 Loop Station

• Boss DD-5 digital delay

• SansAmp Bass Driver digital interface

• Lovetone Brown Source overdrive pedal

• Lovetone Wobulator

• Jersey Girl Plusdriver Boostable Fulltender overdrive pedal

• Behringer four-channel mixer

• Dunlop Crybaby Bass wah pedal

• Electro-Harmonix Micro polyphonic octave generator

• Electro-Harmonix Black Finger optical tube compressor