In the Studio: Chancha Via Circuito

Back in 2007, those looking to find Pedro Canale, the musician who records as Chancha […]

Back in 2007, those looking to find Pedro Canale, the musician who records as Chancha Via Circuito, could most easily find him sitting in the back at Zizek, a weekly club night in his hometown of Buenos Aires, Argentina. (The night would eventually spawn a label and is known these days as ZZK.) There was a party goin’ on, but underneath the noise and flash sat Chancha, patiently manning the merch table and selling a handful of releases from local producers and DJs. The best thing on offer happened to be the smallest item on the table: his own debut EP, which was only available as a 3″ mini CD-R. Those five exquisite songs shaped fragments of South American folk into lucid-dream beat loops, the music aware of contemporary electronic production trends and a dubwise approach to space, but not beholden to either. While many of his peers in the emergent Buenos Aires scene were making mashups or cumbia dancefloor edits, Canale was crafting subtler tunes, unhurried combinations of bass, drums, and melody that seemed simple but always left the room’s air charged with energy.

Seven years later, Canale is still building songs that widen to create spaces. He has no need for big drops or other dancefloor rush dynamics. Many tropical bass producers rely on splicing traditional sounds into the current hot genre—today, the rootsy Afro-Colombian female acapella gets the trap remix, two years back, it got the moombahton remix, a couple of years before that, it got the cumbia remix… and so on. People call this style of global swirl homage, but more often than not, it’s a paternalistic turn, one that treats indigenous music as raw material, something that’s authentic but insufficient, a resource to be extracted then improved by a stacked synth bassline or an 808 kick-and-snare combo.

Chancha Via Circuito’s music takes another tack. He understands that folk music in Latin America is sustenance for those who live it, and is therefore less concerned with sonic newness than he is with maintaining a groove and communicating a sense of pride in place. And the places Canale creates are oneiric, placid, and haunted by unlikely perspectives, like the jungle paintings of proto-Surrealist Henri Rousseau or, closer to home, the Rousseau-inspired, ayahuasca-lit illustrations by Paula Duro that accompany all of his music.

Canale’s studio becomes the arena where he negotiates this respect for traditional sounds and the natural world with the infinite possibilities of digital music production. On the one hand, he uses shockingly realistic German sample packs to play Andean flute melodies. On the other, he’ll get up before dawn to climb Mayan pyramid ruins in Belize, digital recorder in hand, because that’s when the monkeys do their most otherworldly howling. Canale is a producer who keeps a weathered African balafon next to his laptop to remind him not to fall into the computer’s flattening world, and does some of his finest work in the magic pair of hours when his studio receives direct sunlight. The goal is balance.

Last month, Canale returned to the United States to tour in support of his new album, Almansara, which was recently issued via Wonderwheel/Crammed. Coming four years after his last full-length, Rio Arriba, the LP is proof that Canale is not an artist prone to rushing through things. We caught up with him in one of midtown Manhattan’s rare parks, a raft of green beset by skyscrapers and traffic, to learn more about how he creates this music.

Let’s start at the beginning. Where’s your studio?

I have a home studio. It’s in a new place, an apartment I moved to six months ago. It’s really important to me to have some direct sunlight in in there. A lot of inspiration comes when sunbeams enter. In my studio, this only happens for a few hours, so those moments are truly special. It’s important for the energy of the place, for everything.

What’s the heart of your studio?

Interesting question. I think that my studio’s heart is in the balafon. Truth is, I spend a lot of time sitting in front of the computer. You saw the African balafon? Well, I can’t pass by it without stopping to play it for a moment. It’s an instrument that calls out to me: “Come over here! Play something!” It’s always calling me. I got it in Madrid, in an African shop.

How do you start making a song, what’s the process there?

In general, I start making the beats. First of all, I spend a lot time looking for the sounds I want to put in the rhythm. I search sound libraries. And the other part is sounds I record. I also record some instruments, so it ends up being a mix between these three things. The rhythm always comes first. Then I compose the bassline and all the rest.

When you make beats, do you tap them in with a MIDI controller or draw them with the mouse?

I draw them. Just two days ago, I bought an Akai MPD so that I could tap in beats with my fingers. I’d never had the money to get it until now, and anyways, I was used to the mouse. Although I like the idea of programming in beats by drumming with my fingers.

What software do you use?

Ableton Live. For many years, I did everything in Fruity Loops. Rio Arriba was all Fruity Loops. When I discovered Ableton Live, I realized that it was easy to produce the music as well as to play live. There are tons of options to play a show and change things on the fly.

Did doing live sets with Ableton change your approach to working in the studio?

Yeah, it changed my approach to composition. It changed the way I thought about the layers of sound. When I’m playing in front of an audience, I see them and I know—”Ahhh, this doesn’t work, next time this part needs to be shorter (or longer).” So I keep these ideas when I start building a new song.

Some producers can bang out a few song sketches in under an hour, and others will take days and days to outline a song. Where do you fall in that spectrum?

Sometimes I’ll start a song in the morning and I can’t leave it. I’ll feel that I need to finish it in the moment, so eight hours later I’ll have it all finished. Maybe not totally done, but nearly there. Sometimes I start a song and it gets tricky. Then I need more time, four or five days.

Your music isn’t minimal, but it does give the impression that everything is in its place. In a way, it’s similar to hip-hop production, where a whole deep world can be made with just a kick drum, a bassline, and a sample. What’s your approach to using EQs and shaping individual sounds?

First off, I pay a lot of attention to the timbre of each sound I work with. It happens a lot that I’ll want to use three or four different sonic textures, but they’re too close to each other in frequency, so I’ll use EQ to help each one get a bit further from the other. Of course, everything needs to be in its place, for sure. I have a friend who helps me with the mixdown. Andres Oddone, he lives in Mexico. He helped me with my last album and this new one too. He knows how to do the mixdown work really well. I prepare each song as separated multitrack stems and I sit down next to him in his studio. We work together.

What’s his set-up?

It’s all digital! All plug-ins.

So why do you work with him?

Because there’s another part of the mix that’s very, very delicate. The spatial aspect. Many times the EQ is not enough. You need to know the right reverb for each thing, and also the panning. I don’t how to explain it, but there are effects for spatialization beyond left and right, too. This helps situate the mix. It’s too nerdy for me, it depends a lot on programming. Andres uses digital tools in an extremely precise way. I outline an aesthetic for him and he adjusts everything based on that. He asks me how it’s sounding as we go along. At the same time, I give him free path to experiment. If I don’t like it, I tell him. Another interesting thing is that my mastering guy doesn’t use analog gear either. It’s all digital. A lot of musicians I know tell me, “Oh no, why don’t you work with analog?” Well, it’s a lot more expensive and I don’t know anybody who knows how to really use the analog stuff. I know people who know how to use the digital tools really well, and they’re a bit cheaper.

Ableton is your main program, but what third-party software do you like to use?

I like Waves plug-ins. And I use the Kontakt sampler a lot. For example, there’s a song called “Sueño de Paraguay” on the album. My brother asked me, “Where on earth did you find the guy to play that harp?” I told him, “No, I recorded that harp with Kontakt and my MIDI keyboard.” Thing is, it really does sound like some guy playing an actual harp recorded it for me.

The new album seems to have a lot of synths. There don’t seem to be any samples of other people’s music.

Yeah, I did the new album without sampling. On Rio Arriba, there are many samples from other songs. A few years ago, I was told, “If you don’t have illegal samples, we can use this material for TV and film.” For example, my European label, Crammed, asks me not to use uncleared samples.

It’s a shame that nowadays samples are a luxury item. Ghislain Poirier was the first person I heard to break it down like that. Kanye West uses cleared Nina Simone and Otis Redding samples the same ways he uses Versace: it’s another expensive thing he bought. It’s a shame because artists like you can do incredibly beautiful things with samples.

I’m not gonna stop sampling. But all those songs, now I give them away for free. I dropped Semillas, an EP with a lot of samples.

What’s the importance of the space of your studio? Can you work anywhere with your laptop and monitor speakers?

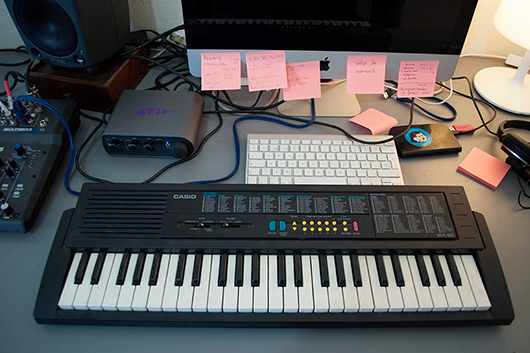

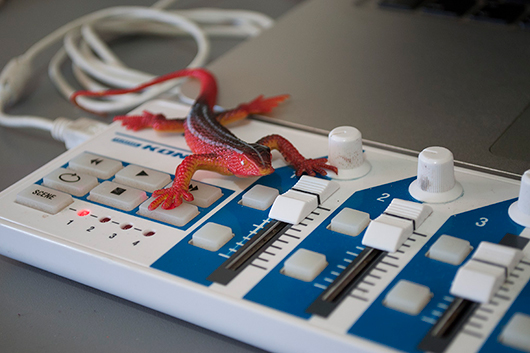

Well, for me it’s important that there are not only electronic objects, but also wooden instruments. I’ve got animals—they’re made of plastic, but they’re there, surrounding me. Snakes, frogs, crickets. I’ve got the monkey doll from Chiapas, Mexico. He’s concentrating, he’s thinking. I don’t like being alone, surrounded by electronics. All this is to have some company. Some friends from the jungle! [laughs]

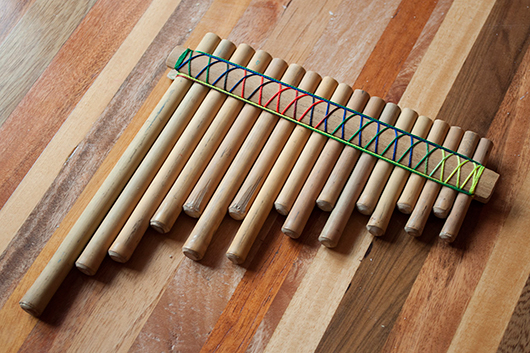

Talking about jungle friends, the physical instruments you have are beautiful, handmade, almost like design objects. Things you want to hold. How does that interact with the flat gray boxes of your music software and screens?

A person can get sick from spending too much time inside the computer. It’s something that demands too much energy from you. There are times when I’ve forgotten to eat because I was stuck inside my computer, obsessing over some small thing. So to have at your fingertips things like guitars, charanga, flutes, marimbas, the balafon—they’re ways to escape. To have organic stuff, there’s a direct contact there that’s necessary for a good energy balance. Sometimes I think about all the waves that pass through us. Wi-fi, mobile phone, TV antennae. We’re all shot through with a mountain of signals. And if your studio has a lot of electronic gear on top of all that, it becomes way too much. I need to look into it a bit more. There has to be a way to calm things down. Maybe with a little water. Maybe with more plants. There must be a way to compensate for so much energy radiating out of the electronics. Feng shui is an important art for a reason!

When most musicians get their studios discussed, it’s because they own a lot of gear, vintage synthesizers or fancy compressors or whatever. But I’m like you: I have a laptop and that’s that.

I have to confess—when I saw the photos of the other In the Studio pieces, I thought, “Well, I don’t have anything compared to that.” The other studio profile pictures look like a synthesizer catalog. I honestly didn’t think this was gonna happen! At the same time, I’m not the stuff I use. The sound card I use, who cares?

To be honest, I don’t understand the gear fetishist studio vibe either.

It’s really North American. Because they’ve got access to buy so many things. For me, it takes months to gather the money to buy something. It’s another mentality. Whatever I can buy becomes truly valuable to me. It’s worth a lot to me and I take a lot of care with it.

Let’s talk about your turntable. There’s only one, so it’s for listening; you’re not DJing with it.

I bought it at the end of last year. It was glorious. I’d been buying vinyl records for more than a dozen years, almost 15 years. Buying them, thinking and looking forward to the day when I could listen back. I never listened to them. I’d dig through record shops, find stuff, and store it all in my parents’ house. This record player I bought from Oro11—you can tell because there’s a Jesus figure on it. After I got it, I went to my parents house for my records and it was like opening up a treasure chest. Now I’ve got the sickness! [He points to bag of vinyl he’d just bought] There’s no looking back now. I go to a city and I want to find all the record shops. You’re writing about all this stuff, how listening itself changes with new technologies. Now more than ever, I realize that it’s crucial to listen to an album from start to finish. With MP3s, this never happens. You choose what you like on first listen and delete the rest. Now I’m returning to listen to music when I have the time to really pay attention to it.

What about the digital recorder you use out in the field?

It’s an M-Audio. It recently broke. It was weird though, it broke recording black howler monkeys. Do you know what they sound like? I was in Belize. I was there on top of a Mayan pyramid called Lamanai. They had told us to go at four in the morning. Everything’s dark. When dawn breaks, the monkeys begin to howl. [He lets out a surprisingly realistic monkey howl in the middle of the park] It’s such a powerful sound that you’d think they were tigers. And then the recorder broke, like it said to me, “That’s enough!” But only after it had recorded the monkeys howling.

The place had such a heavy energy that it didn’t seem strange or crazy that something electronic got broken. Like nature was saying to the gear, “What are you doing here? Get out!”

“You can listen to this but nothing else—this is the last thing you’re gonna hear!”

Yeah! Nature or the spirits of the people that lived there—nobody knows. Places like that hide their secrets. And that’s the story of my broken digital recorder.