In the Studio: Matthewdavid

Over the past few years, the loose network of LA-based producers and DJs who have […]

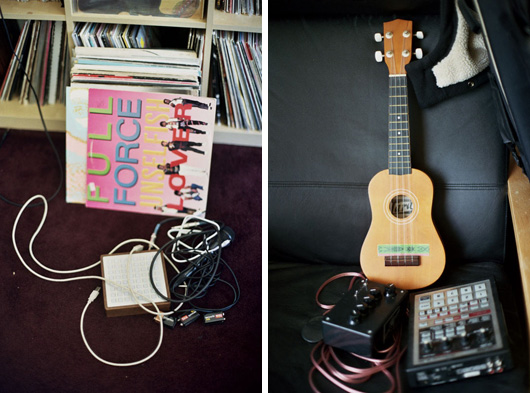

Over the past few years, the loose network of LA-based producers and DJs who have been lumped together under the (admittedly murky) umbrella of the “beat scene” has become rather crowded. Nevertheless, a few artists within that world continue to stand out as true originals, one of them being Matthewdavid, the Brainfeeder-inked sound experimentalist who also heads up the innovative Leaving Records imprint. XLR8R actually ventured into Matthewdavid’s home last year, around the time his Outmind LP was making its way into the world, but we decided to make a return trip, this time in hopes of getting the skinny on the artist’s production methods, gear preferences, and studio secrets.

XLR8R: How long have you been making music?

Matthewdavid: Since I was 15. I’m 28 now. It started when I wanted to make rap beats and rap over my beats in high school. My friends were making this music on the computer using Fruity Loops. I didn’t know anything about that, but I wanted to do it. So, it started off as a tip from friends who were making rap music on Fruity Loops and I got that shit for free and got Acid, Version 2 or something. I was doing really basic multitracking in Acid with my beats from Fruity Loops and I would record vocals on my mom’s PC using the built-in computer mic. I soundproofed my bathroom and recorded these albums in high school.

So your initial production was all on the computer?

Yeah, when, I started making music seriously, it was all computer based. I had taken guitar and piano lessons as a kid. [In high school], I got my first set of turntables. I remember teaching myself to blend, mix, scratch and in college, I began to take it more seriously and became a really serious scratch DJ. I was incorporating that into my production, and then when Ableton came around, I started integrating the scratch/sample-based stuff with the programmed drum hits and electronics. And then, I moved away from hip-hop completely, but I’m coming back to it.

Were you sampling?

Kind of, but not sample-based music. I would put funny helicopter sounds or bubbles—fun, playful sounds that were samples, but it wasn’t really on that level of me seeking out or collecting music to sample from. It was just funny WAV files from early internet sound archives. I dove headfirst into making beats, kind of ignorantly, but later on, after I started doing my homework on hip-hop, friends tipped me off and put me in place about where hip-hop came from and sampling. So, sampling came in two, three years after I started [making music].

You mentioned getting away from hip-hop. When did you start to get into ambient and experimental sounds?

I was really late on going to punk/noise/experimental shows. Hip-hop was my outlet for counterculture, or “punk.” When I got out of high school, I went to the big state university in Florida and all this other music was around. [Around this time,] Ableton, electronic music, and synths were taking over, and I became very sensitive to sound. I was less wanting to just make beats and more interested in sound. That kind of took over, so when I moved to LA, that’s all I was interested in. Getting in with Dublab and going to Dublab events really blew my mind wide open. I started taking that stuff seriously and becoming a producer in the sound-design sense, spending a lot of time with tone, drone, and field recording. I met Flying Lotus, and he was really interested in what I was doing. Then, from meeting him and his whole crew, I got back into hip-hop, but then they were interested in me because I was doing something new.

In terms of making those elements of your music—tone, drone, etc.—what equipment are you using? How much of it is organic versus the computer?

That’s always a strange, blurry sort of line. I make a lot of it in the computer, but it’s about a lot of self-studied process, a lot of self-discovery, a lot of experimentation, a lot of patience with making it sound [a certain] way, the processes and the ways to go about making [a particular] sound happen. A lot of it is made in the computer, recorded all in the computer and taken out and put somewhere else—on to tape, quarter-inch tape, reel-to-reel, cassette, or through outboard compression or outboard gear or whatever—and then put back in. A lot of times, just parts of the song’s instrumentation will be rendered out as this small part, so I won’t be taking the whole song and translating it to an analog world and putting it back. I take parts and do it that way. It’s really always varying. When I was in the initial stages of getting into ambient music, I shut my computer down, closed it and started tracking on 8-tracks, 4-tracks. I had never recorded like that, in the traditional way, and I thought it was really interesting what I could do with that. I was really into things being all analog at this point, but then I realized [that] was stupid and [decided] I should just do both. But I’ve always been really interested in more folk and acoustic instrumentation, just as much as I’ve been into synths and full electronic instrumentation. I try to make it work and bridge the gap and make those things sound interesting.

Your music sounds really warm and has an organic nature to it. How do you achieve that? Is it plug-ins? Microphones?

It’s a combination of all of it, and a lot of time experimenting. There are a lot of little secret tricks, a lot of real obvious stuff, but it’s all about the combination and just the patience and sensitivity to the process and the sound. [It’s important] to not really become impatient or fed up with it all. Instead of being the mad scientist who stays locked up in his room all day, I go out a lot and listen to a lot of music. I’m influenced by a lot of stuff, and not just music, but sound. I’m very sensitive to public spaces and sound, whether there is music or not.

Would you say your production process is always changing, even from song to song?

Lately, I’ve been into really dry recording—not effected, not wet or compressed. Everything was heavily effected and compressed on my album and a couple of my ambient tapes. Everything had that super-saturated, organic, warm, textural, compressed, tape sound. But now, I’m into not having that sound and making my shit more clean and dry. I’m approaching recording, tracking, mixing, and production in a more traditional way. I’m hearing how records were cut in the past and trying to hone in on that instead of being more obscure. I’ll always have that [old process] and I’ll always keep doing that. That stuff is great and fun and really meditative for me to make, but lately the directions are moving away from this process that I’m known for.

Did you get to a point where you didn’t want to be known as the tape-saturation guy?

[Laughs] Yeah.

In your sphere of electronic music, you were ahead of the game on cassettes. When did you get into them and what attracted you to the format?

I started going to these weirdo shows in college. I was seeing all this crazy music, and then seeing tapes at shows. That shit had been happening for years, it was nothing new. It just made sense to me. I was making really strange music at the time, and I just felt like [cassettes] were the home for that music, just because of the way it sounded. I was interested in what the tape did to the music that was put on it.

What are some of the ways that you incorporate them into your production?

One of my secret processes are tape decks with pitch control. TASCAM or Fostex [decks] have the big pitch knob. You can record shit to that… and then if you slow it down in that analog way, it makes [the music] sound a lot cooler, better, more organic. That’s what I do a lot with tapes that I find. I sample and slow it down on tape decks with pitch control.

Do you use any analog drum machines or synths?

I don’t. I’ve been borrowing some stuff lately, but I don’t have any of that. I have a weird synth in my room that Flying Lotus is letting me borrow right now, this funny-looking Roland thing. It’s a digital synth. It’s got great sine-wave bass. I’m really comfortable and I feel like I know my way around synthesis after dealing with synths for a long time. I’ve had this one digital E-mu synth forever. I’m not so comfortable with virtual synths. Something about them, I’ve never been able to use them. I need something to play and see and feel and touch. For drum-machine sounds, I just have a bunch of kits on my computer that I put into Ableton—all the Roland kits and stuff. I have friends with crazy analog gear and I’ll go and sample/use/borrow, but I’m more into playing guitar and hand percussion. I have one condenser mic that I’ve had for years and that’s another secret weapon of mine—this one Sleeper condenser mic that I got for $150 in college. I’m really into playing my Casio SK-1, which I use on everything all the time.

Is there any gear or musical equipment that you’ve been lusting after?

I really want an analog synth. I’ve never had one. I’ve been into playing keys a lot more lately, learning scales. Dam-Funk really inspired me. I played a couple of shows with him last year (with the Master Blazter band). Seeing those guys play, I thought, “Man, I need to get back to piano. I need to get back playing.” Computer Jay and Dam-Funk, they have these crazy synths, crazy Moogs, crazy things. I want an analog-synth keyboard. I want a Moog. Here’s the thing though. I’m always going back and forth. Having a really shitty, cheap, low-end or budget-grade synthesizer—those things sound great. It’s just me, being really nerdy and the music nerd that I’ve become, and the sound that I’m after, I just feel like I need an analog synth. But those things are expensive and the things that I want in an analog synth, you can’t get in every analog synth. There are always things I’m lusting after. I’m lusting after all sorts of new tape decks, too. I want to find these broadcast-grade, studio/pro rackmount tape decks. Those are really great quality, and have the pitch and all the little extra qualities on tape decks that I’m always after. All my tape decks are breaking all the time. These tape machines, they don’t last. These things break! Everyone is always asking me how to get these things repaired. Actually, no, you just need to find another tape deck. With these old, analog machines, the time it takes to seek out someone who’s going to repair this thing, and the cost of parts (and finding parts)—some of these parts, they aren’t even made anymore.

When making songs, do you follow a set writing process?

Lately, I’ve been starting with a sample or loop, just a really small loop that I really like, maybe a one-bar, two-bar, four-bar loop that I can play over and over. Something simple, fundamental, and existing by itself. Things build from there. A lot of times, that loop can be a drone or ambient thing. Ambient music is more easy for me to make. That’s kind of my folk music. I can make it any time and I have to make that stuff, otherwise I’m not me and I don’t live. When it comes to beats, I start getting really technical and scientific and nerdy. That’s when the structure starts happening.

Are you of the opinion that you don’t need analog gear to make analog sound?

Yeah. That’s basically what I do. I record digital music put to analog to make it sound analog. A lot of people don’t understand that’s how I get my sound, but most of it is all digital. But it doesn’t sound that way, because I take the time. I’m really into pedals and outboard processing units, too. I love all the crazy effects and plug-ins that I use in the computer and Ableton for effecting, but analog delay is a really big thing for me, too.

The end product of what you’re making rarely sounds like a traditional pop song. How do you know when your songs are done?

I don’t know, that’s interesting. Something I really like is how I sequence material for my music or other people’s music that I’m putting out. I really love ending things abruptly. I don’t like long fadeouts—I think that’s a cop out. If I don’t know when a song ends, I’ll just say this song is over, here. [snaps] I think it’s really strong and sort of a powerful statement when things end like that. It makes sense. There’s something really “punk” about that, which I always intake to my process.