Event Review: Berlin Atonal

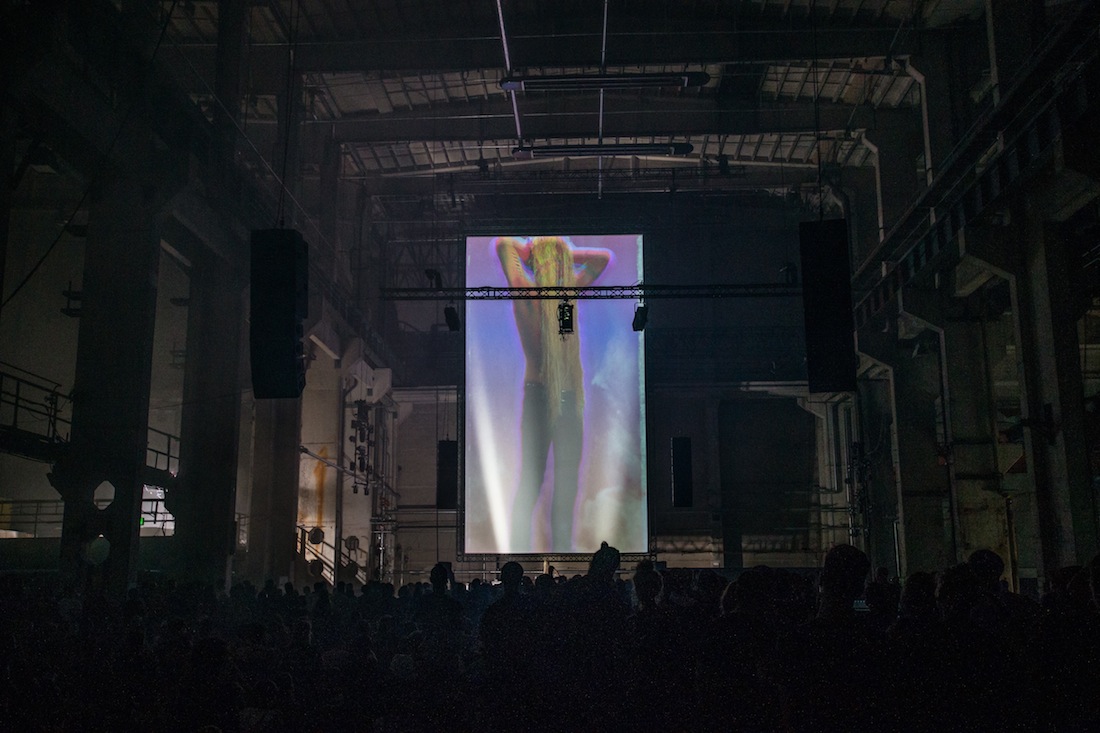

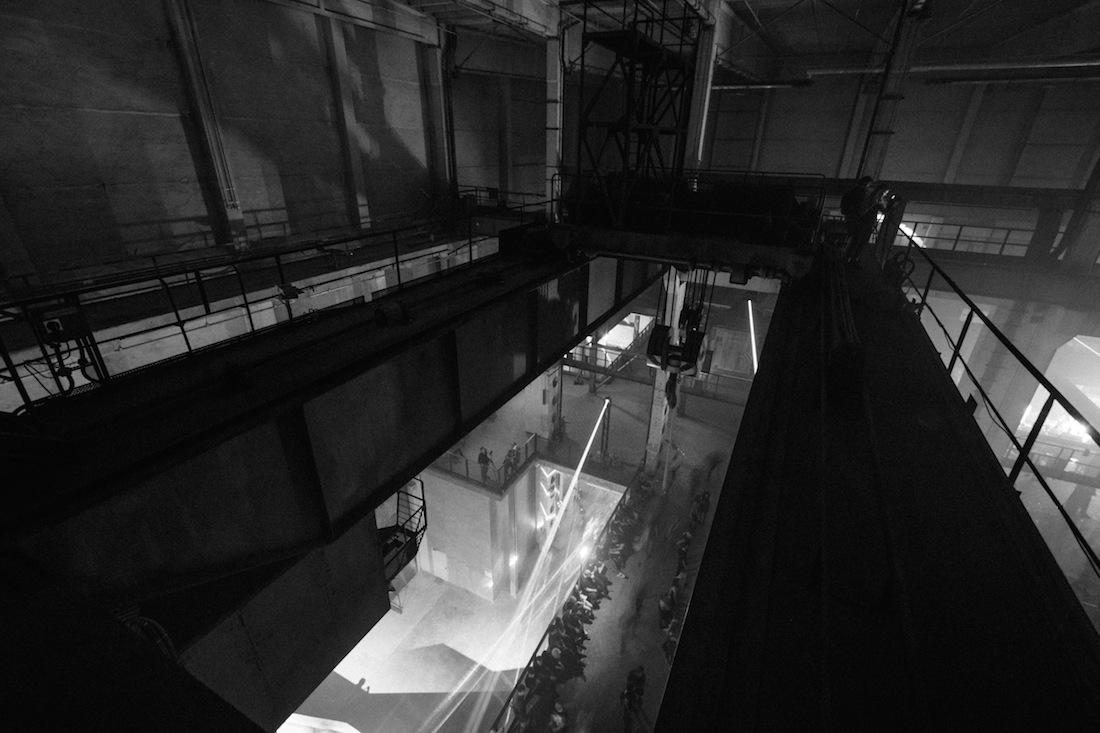

The experimental arts and music gathering returned to the grand setting of the abandoned Kraftwerk power plant.

Originally founded by Dimitri Hegemann in 1982 and officially relaunched in 2013 by Laurens Von Oswald and Harry Glass, Berlin’s Atonal festival was held at the abandoned Kraftwerk power plant in Mitte from August 19 through the 23rd. The series of music shows and audio-visual art installations that were at the heart of the festival left behind an impressive and extensive legacy. Although XLR8R missed the opportunity to attend the first two installments of the relaunched fest, its weighty contributions to the music and art worlds are so well known that the festival has turned into somewhat of a cultural institution, making us eager to see what this latest edition had in store for us.

From the moment XLR8R set foot onto the magnificent venue—a concrete, cathedral-like structure, with an atmosphere evocative of a Lynchian film and with a spread of art installations rivaling the infamous MONA museum in Tasmania—the bar was already set extremely high. And how could it not? This is a festival that for many years was at the forefront of the electronic and experimental music and art scene, meaning that it has a lot to live up to. The venue’s concrete, open-plan interior, with its exceedingly high walls and pillars, made one feel extraordinarily minute against the immensity of the venue’s backdrop—and even with the obvious careful curation and overall planning of the event, the setting seemed to take a bit of the spotlight away from everything else. This wasn’t entirely a bad thing—but for a festival that was founded on the basis of pushing boundaries, we didn’t feel as though that were the case.

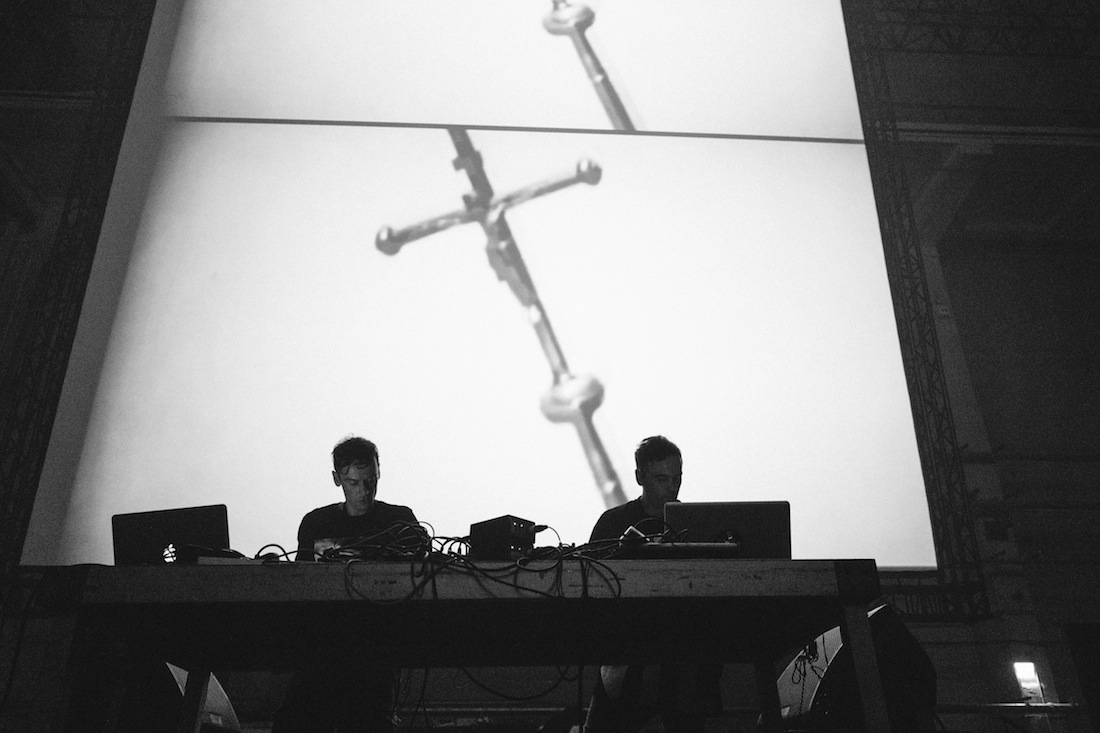

There were a lot of performances that did not live up to the expectations: David Borden and the Mother Mallard Ensemble’s kitschy synths rendition felt too outdated and dull for the occasion, for instance, and Shackleton’s Powerplant premiere was somewhat of a let down. Powell delivered one of his signature, high-energy, industrial-tinged breakbeat-techno sets—it was good, but in light of what the festival stands for, perhaps not adventurous enough. There were still some remarkably beautiful and standout acts worth mentioning. Max Loderbauer and Jacek Sienkiewicz carefully painted beautiful drone soundscapes which paired up with explosive projections in the background, all fitting together impeccably well with the mood of their eloquent set. A set from Regis and Ancient Methods, partnering up as Ugandan Methods, was also a grand success: Theirs was one of the rare performances featuring any beats to speak of, and they delivered a beautiful industrial-techno set that came as a breath of fresh air when contrasted with the rest of the festival’s drone monotonousness.The mise-en-scène of their performance was particularly striking—it was juxtaposed against the stunning cinematography of 1928’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (from director Carl Theodor Dreyer), re-edited in a way that matched the mood harmoniously. However, there were only a few of such standout acts, sadly not enough to compensate for many of the other, unexciting performances as a whole.

There is no denying that Atonal was extremely beautiful. Aesthetically speaking, it was grand, pure and candid. But for as much beauty as was conveyed, many performances altogether felt lackluster at best, leaving us craving for more. Bear in mind, this is a festival whose whole foundation was based on the purpose of providing artists the freedom to experiment freely—but unfortunately, this year fell short of that. While aiming to recapture the avant-garde and countercultural spirit it was once known for, it seemed as though many performers lost their voice, drowning against the surroundings that took the center stage—as if those surroundings were carving out an impossibly huge space to fill. Many of these acts felt similar to one another; in the end they seemed to merge together as one extended, drawn-out, drone soundtrack, one that stretched out for too long a time. The task of differentiating among performances became something of an effort, and perhaps five days was too much for the festival as a whole. We found ourselves questioning whether Atonal’s current popularity lies mainly on the hype surrounding it.

Atonal certainly has the makings of a unique and powerful event—and XLR8R remains hopeful that next year’s edition will be able to deliver more than just an aesthetically pleasing experience.

All photos: Camille Blake