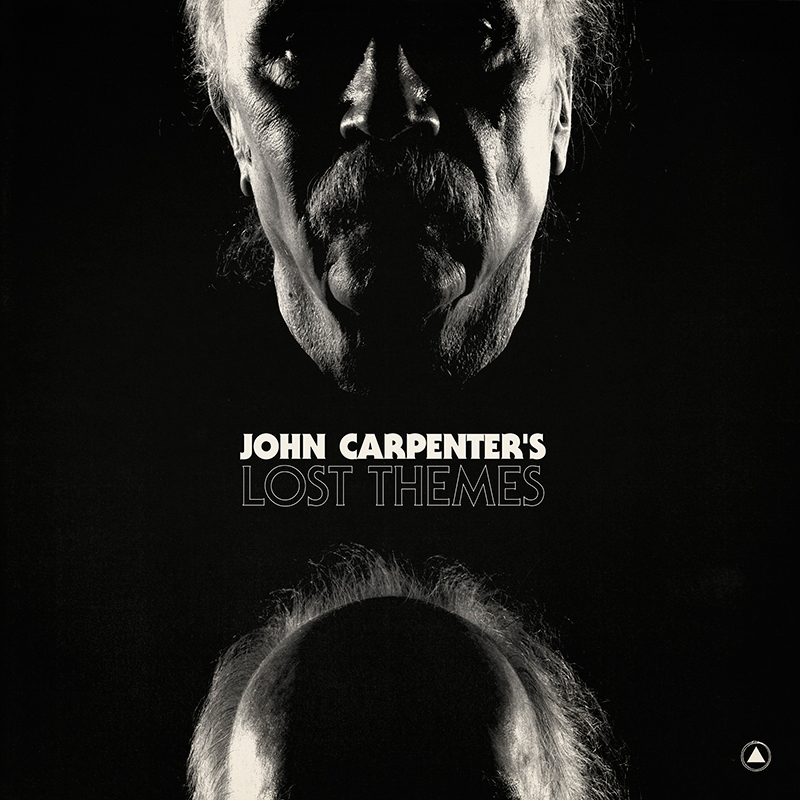

John Carpenter Lost Themes

The master director and composer stretches his legs—a bit—on his first-ever artist album.

Lost Themes is something of a post-modern marvel. After all, John Carpenter is one of America’s most beloved filmmakers (amongst a certain cadre of viewer, at least), a figure who’s responsible for a spate of the best horror, action, and dark comedy films of the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. Essential to his films’ success were their soundtracks—sparse, simple, all-synthesizer affairs rife with tension, dread, and drama, all of which were composed by Carpenter himself (occasionally in concert with Alan Howarth, a frequent collaborator). Over the years, these soundtracks have proven to be so effective that they’ve inspired legions of imitators, including a bevy of electronic musicians who hew so close to the Carpenter blueprint that they blur the line between homage and appropriation (see Umberto, Xander Harris, and Cliff Martinez’s soundtrack to Drive for glaring examples). Surfacing after a long period of relative quiet, Lost Themes is Carpenter’s first non-soundtrack album, and was written with no accompanying images to score to. It is, essentially, John Carpenter performing as John Carpenter, a slightly surreal situation in which the auteur has become so notorious that he riffs on his own notoriety—a musical 8½.

But that’s all somewhat beside the point—is Lost Themes a good record? Yes—with a few reservations. The LP contains nine tracks, averaging about five and a half minutes in length, all of which have evocative one-word titles plucked straight from the Carpenter oeuvre. They’re more accurately described as suites or medleys, each one consisting of short pieces stitched together, giving the album a true “soundtrack” feel. The sound palette is classic Carpenter, with some haunting, spooky bits (“Fallen,” “Night”) and a good deal of gloriously cheesy guitar riffs and rockin’ drums during the uptempo pieces (“Domain,” “Abyss”). The album is relentlessly cinematic, almost oppressively so, which makes listening to Lost Themes from start to finish a bizarrely visual experience; whereas a great deal of electronic music is remarkably open to interpretation (this being one of the genre’s greatest strengths, arguably), it’s difficult to listen to Lost Themes without imagining a burly action hero bursting out of a burning building or a masked murderer silently stalking his prey. Granted, this may or may not be to the listener’s taste.

The digital edition of the album includes six remixes from a well-selected collection of artists who were clearly influenced by Carpenter: Zola Jesus with Dean Hurley, ohGr, Silent Servant, Blanck Mass (a.k.a. Benjamin John Power, half of Bristol duo Fuck Buttons), J.G. Thirlwell, and PAN boss Bill Kouligas. Their efforts range from good to excellent; Zola Jesus’ contribution, in which she lends her searing voice to the throb of “Night,” is a standout, as is Blanck Mass’s rework of “Fallen,” which transforms the original into a slow-burning psychedelic drum track that builds toward an explosive climax.

In the press material accompanying the record, Carpenter says “Lost Themes was all about having fun,” and it shows. It’s suffused with a particular kind of glee, the kind that comes from having mastered one’s craft inside and out. At the same time, that kind of mastery comes with its own kind of limitations—there are no surprises here, for better or worse. Furthermore, the fact that Carpenter’s studio has expanded significantly since the Halloween days means that the incisive, cutting simplicity of his early work is nowhere to be found. In the end though, none of this matters too much, because Lost Themes is a still blast to listen to.