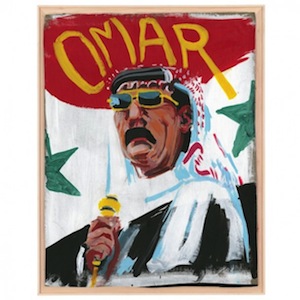

Omar Souleyman Wenu Wenu

For most Western audiences, the type of dance music Omar Souleyman creates and performs is […]

For most Western audiences, the type of dance music Omar Souleyman creates and performs is sonically familiar, but culturally unrecognizable. Though his career spans multiple decades and he boasts an impeccable reputation in his native Syria, it’s the involvement of Kieran Hebden (a.k.a. Four Tet)—who was enlisted to produce Wenu Wenu—that has truly boosted Souleyman’s profile as of late. Still, even with Four Tet behind the boards, Souleyman’s foundation remains largely the same, as he continues to use the Syrian wedding music known as dabke as a jumping off point. Designed for group dancing, dabke’s communal energy is well presented on Wenu Wenu, particularly in the hyperactive arrangements of Souleyman’s composer, keyboardist, and longtime collaborator Rizan Sa’id. The frenetic songs are at odds with any expectations of foreign antiquity, and on the whole, Wenu Wenu is a giddy digital blur.

Opener “Wenu Wenu” is a shove into the dance circle, with chord stabs shuddering underneath a slithering synthesizer line that’s as hummable as it is peculiar. The synthesizer, ascending and descending frantically on a quarter-tone scale, has a memorably trilling timbre somewhere between theremin, bagpipe, accordion, and 303, and it’s the album’s instrumental anchor, returning again and again. “Wenu Wenu” hurdles toward a fantastic breakdown, with rhythmic shouts egging on Sa’id’s spindly instrumental pyrotechnics that suggest AC/DC finger-tapping. Singing entirely in Arabic, Souleyman’s craggy voice has a dynamism that doesn’t require translation. Still, the dominant themes on Wenu Wenu center around a romantic yearning that’s barely masked in celebratory fervor. On the gentle “Mawal Jamar,” Souleyman laments an unrequited love, singing “I would walk on coal for you and dig my own grave before I see you getting married.” Other lyrics entreat God to watch over a forbidden love, both in the breakneck synthetic horn charts of “Ya Yumma” or the blippy “Warni Warni,” in which Souleyman sings, “May God punish whoever tries to separate you and me.”

Those expecting a Four Tet record will be sorely disappointed. Wenu Wenu is Souleyman’s first album recorded entirely in the studio, but Hebden had only a perfunctory presence during the recording process. However, just having his name attached means that Wenu Wenu is bound to draw attention from listeners whose eyes would normally glaze over within seconds of hearing the words “Syrian folk pop.” As it stands, Hebden’s fingerprints are practically anonymous beyond the propulsive energy that Souleyman’s arrangements and Hebden’s recent ramshackle productions share.

Wenu Wenu‘s success lies in its ability to cleave memorable passages from homogenized surroundings. Even when the instrumentals stagnate, Sa’id contributes plentiful moments of virtuosity or adds ornamental fillips to complement Souleyman’s emotional tone. Listeners will be able to highlight any variety of neon moments as favorites with little overlap because the album is so stuffed with detail. “Khattaba” has a hip-hop slinkiness, while “Yagbuni” is a defiant and dark closer, phasing random phrases on top of soft piano-house chords.

If Wenu Wenu has a weakness, it’s that the music is one-dimensional. Then again, wedding music isn’t exactly known for genre diversity or abstraction, regardless of the culture. Considering the intended functionality of Souleyman’s output, homogeneity isn’t necessarily a problem. However, the overwhelming digital palette still makes for a tiring listen. On a song like “Nahy,” even an undulating flute sounds aggressive, though in the context of the album it’s a comparative respite. Finishing Wenu Wenu brings on the equivalent of runner’s high; one is left feeling the adrenaline rush but still panting for breath.