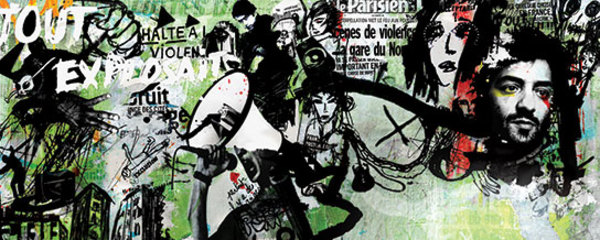

Paris’ Youths Rock the Mic

The first time the dilapidated French suburb of Clichy-sous-Bois made worldwide news in 2005, it […]

Paris’ Youths Rock the Mic

The first time the dilapidated French suburb of Clichy-sous-Bois made worldwide news in 2005, it […]

The first time the dilapidated French suburb of Clichy-sous-Bois made worldwide news in 2005, it was for a cultural moment more offbeat and innocuous than anything else. That July, the city became home to the first Beurger King restaurant, a fast-food chain that serves meat according to Islamic halal tradition (the name references Beur, a slang term for second-generation North Africans living in France). The waitresses even wore traditional headscarves. Building on the success of Mecca Cola, another French product geared towards the country’s large Muslim community, it seemed like an unlikely story of cultural adaptation and perhaps integration.

Two years later, integration is the last word that comes to mind when one thinks of the city. In October of 2005, angry French rioters made worldwide headlines by demonstrating the true extent of their country’s social divide. Spurred on by the death of two teenagers–both electrocuted in a power station in Clichy-sous-Bois where they hid while evading police–angry residents of the immigrant-heavy, working-class French suburbs, or banlieues, erupted, starting 20 straight days of violence and rioting. The country declared a state of emergency, but the damage was already done–integration and social tensions in France now have a dark new symbol.

Visions of angry, disorderly youth have been a wedge issue in French politics since, and a reoccurring fear for those who see poor immigrants as an impediment to social integration. But sensationalizing politicians rarely, if ever, get to the root of the problem.

“What you call ‘the riots’ were grossly exaggerated and were nowhere near as bad as they were portrayed on TV,” says French-Algerian pop star Rachid Taha. “Remember that it was just before the elections, and these ‘riots’ allowed certain politicians to take a position that would attract the voters they were chasing.”

The real voices of this disenfranchised portion of French youth can be heard via the country’s massive, longstanding hip-hop scene. There has been plenty of talk from politicians, who act as if the social tensions revealed by the riots are like a guillotine hanging over France’s head, ready to cleave the fragile Fifth Republic in two. And there have also been plenty of self-serving condemnations of hip-hop by politicians in France, who say blunt language on many releases inflames current tensions. French legislators have repeatedly ordered the country’s justice ministry to prosecute rappers under hate-crime legislation, especially after a successful case against Suprême NTM (NTM being short for nic ta mère or “fuck your mother”) in the mid-’90s.

Mostly teenagers and twenty-somethings whose parents immigrated from the Arabic world (including many former French colonies), these residents of the disconnected suburbs that ring the City of Light and other French metropolises live in areas that can sometimes register unemployment levels of 40 percent. It’s a living situation ripe for despair, disenfranchised youth, and expressive, aggressive hardcore hip-hop.

“The problem of the youth from the suburban ghettos is not an immigrant problem but more of a social problem,” says Nawal, a Comorian-born musician who now resides in France. “We are confused between problems of the new generation and an immigration problem. The kids who burned the cars are French. Sure, their parents came from a foreign country, but most were born in France. They express their anger being born in the ghettos and living in areas that are seedy, run-down, depressing, without color and without hopes. They’re angry at feeling like they have no future.”

Home to the world’s second-largest hip-hop market, France has been turning out homegrown MCs like Disiz la Peste and Senegal-born superstar MC Solaar since the ’80s and the rise of Sidney, a Parisian DJ who started the influential Rapper Dapper Snapper show at the dawn of the hip-hop era. It was soon recognized as a perfect platform to voice rage and despair over the social inequality and lack of opportunity that plagues the banlieues, and soon hardcore French rap took shape. Similar in subject matter to American gangsta rap, crime dramas, resentment at social inequality, and anti-police screeds appear often.

While the suburbs are often portrayed as drab and filled with housing projects, there is a cultural vitality and variety to this melting pot of immigrants from Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere. It can be heard in rhymes composed in verlan, an invented and somewhat inverted slang language of the French ghettos.

Hip-hop has also provided an important outlet for social protest, social reflection, and perhaps social change. Much of this anger and tension finds its way into French hip-hop. Le Havre-based rapper Medine whose introspective 2006 record was called Jihad: The Greatest Struggle is Within Yourself, wrote an editorial for Time magazine right after the riots, asking the question, “How Much More French Can I Be?” Good question. And until it’s addressed, it’s impossible to know if France can live up to the old slogan of liberty, equality, and fraternity.