In the Studio: Apparat

Intimate conversations with the Moderat man.

In the Studio: Apparat

Intimate conversations with the Moderat man.

Sascha Ring’s latest Apparat album, LP5, followed two albums as Moderat, the band he formed alongside Gernot Bronsert and Sebastian Szary of Modeselektor. Not only was it his third release on Mute, but, with its pop song-craft and diversion from electronics, it felt like a logical progression in his ongoing evolution since he joined the British label with 2011’s The Devil’s Walk LP. He recorded the album in Berlin, Germany through 2018/19, although much of the basic production work was completed in a two-week spell alongside multi-instrumentalist Philip Thimm, a staple of Ring’s solo work, and Jörg Waehner, his regular drummer. He also teamed up with John Stanier, from Battles, at Hansa Tonstudio, famous for its hosting of David Bowie.

Behind Ring’s transition is a diminishing interest in synthesised sound. He discovered house and techno around the turn of the millenium, and, working with an Atari, he released his first records in 2001. He maintained a steady release schedule over the ensuing years, but, as he become dissatisfied with electronic music, a craving to revert back to songs informed his music-making practice.

“I listened only to electronic music for like 10 years, and then I realised that there’s like this whole universe of post-rock and classical music, and suddenly electronic sounds became boring for me,” he explains. Add to this Moderat, formed in 2003, and an expanding body of work in film and television scoring, and the reasons behind his move from IDM-informed glitch to melancholic pop become more clear.

Ring’s work in film and television is more evident on LP5 than his earlier work, and, as a result, it feels even more distant than anything we’ve heard from him before. “I wanted to think some more on arrangements, and having some turns and some changes into directions you don’t normally expect,” he explains. “This is something that I learned in film scoring, where there isn’t the traditional structure: song, chorus, etc.” Ahead of his new live tour, Ring connected with Luke Cheadle for what turned out to be a rare, in depth insight into his working mind.

You released LP5 earlier this year. How did you go about recording it?

I was trying to do something I hadn’t done before. This time, for the first time in my life, I wanted to do jam sessions with a lot of people in the studio, and to make things happen that way. I was shocked at how long it took but I think this is due to the fact that I am the weak point in the band; I have never been good at playing instruments. We were in the studio for two weeks and we recorded tonnes of stuff but only a couple of minutes ended up on the actual album. Anyway, that was my concept in the beginning, and when I realised it wasn’t going to work I went back to my normal workflow. It became a hybrid version, where I still invited a lot of people, but it was pretty constructed. Even though I wanted a human record, it ended up being a computer record.

What led you to this jam-session approach?

I think it mostly stems from the movie and theatre music I’ve worked on. In 2012, we did the music for Tolstoy’s 1869 epic “War and Peace,” and performed this live in a theater around 15 times, and so we became good at playing the material. After that, we went to the studio and made a record based on the music we were playing there, Krieg Und Frieden, and that felt liberating. Very often after you’ve played a tour you think you should record the album then because you’re so good at playing the material and you can be much more free with it. It’s always a bummer to me that once you’ve played your shows, and you’re really good at the material, you just drop it and move on! So that’s what we did; recording it was easy instead of a painstaking two-year process. So with this album we tried to recreate that by having lots of ideas that we would take to the studio to perform, but it wasn’t the same because we hadn’t actually played the material before!

Did you find yourself drawing on these original recordings, for samples?

Yes, I would take sounds from there and then make a collage with the newer recordings. It was actually quite nice because it meant that I had a huge pool of samples. But it also felt like it was a bit of a waste because none of this “humanness” made it onto the final record. However, a part of me has always wanted to make a record that’s made out of lots of little interesting things, like a collage of sorts, and so it was important to have this big bank from which I could take bits and pieces.

What were the main pieces of gear that you used to record the album—you had Philip Thimm on cello?

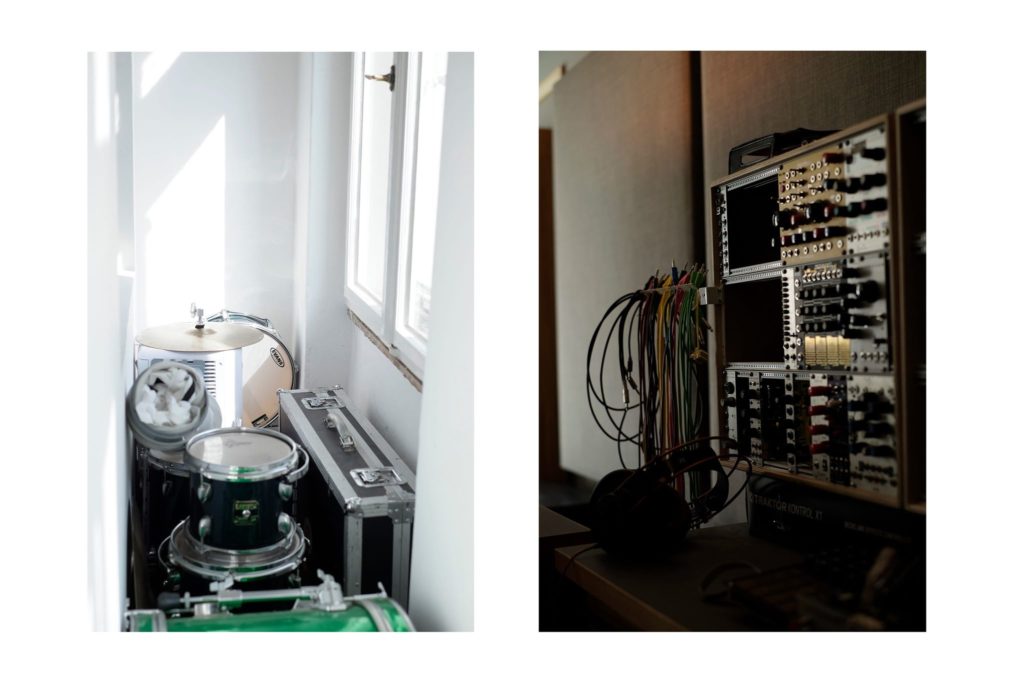

Yes, Philip is basically my human sampler. He plays almost every instrument except drums, and I’m glad because otherwise I’d think he was too good and it would actually be scary to work with him. What you hear on the album are lots of recordings from these instruments; there wasn’t any spectacular gear. I had to switch off my modular because otherwise I would never have finished the album. Right at the beginning, before I wanted to make a human record, I actually thought about making my first electronic album in 20 years, with a modular system; I tried that for a year, but at some point I thought Fuck that, it needs to be off. I’d have gone down the wormhole and never have released anything ever again.

So it’s almost entirely sample-based?

Almost entirely. The only synths in there are bass sounds. There are a few pads in the background but almost all the sounds are samples. We also often put piano through granular effects.

The drums feel quite loose, too.

Yes. In the beginning, I actually wanted to do a more energetic record but I just couldn’t because when I am in the studio I always start switching off drum tracks and I get into this zen mode, where everything is hypnotic. We had some sessions with John Stanier, from Battles, and we went to Hanser Studio in Berlin, which is where David Bowie used to work. I have so much material from that session but it just wasn’t the right album for intense drums, so what is left is a lot of sampled human drumming, some from Stanier and also Jörg Waehner, who has been my drummer for a long time.

How did you actually find your way into production?

The first big step was buying some shitty turntables, and then Technics, which satisfied me for two years. This led me to wonder about how the music is made. I remember that I had a friend who was actually producing, which was really exotic for the area I come from, and he would lend me a Juno 106. I turned it on for the first time and I expected to make every sound with it! That’s how naive I was; I had no fucking idea, and so I had to go from being a totally ignorant rave kid to becoming a producer. The biggest step was when I moved to Berlin, in 1997, and I sold my Technics, and I bought an old Atari and a shitty sampler, which had about one per cent of the memory that a phone has right now. With that, I started producing.

How does the approach on LP5 compare to your earlier work?

Over the past 10 years or so, I’ve become really tired of being really nerdy in the studio, and doing things that take a long time, like editing and sound design. I was really into that when I started; that was actually my main interest in making electronic music, and way back then it was even nerdier because there wasn’t a plug-in for every sound. I would spend three days just programming a sound, and at the end of it we’d be celebrating it so much. This just doesn’t work for me now, and it hasn’t done for a long time. That’s why I started playing instruments: the outcome is direct, and it’s really a lot more satisfying. That being said, I think I’m finding my love for nerdiness again, and on this record I did do some long nights, even if it’s not so obvious.

Yes, there was a clear shift to a more song-based approach, around The Devil’s Walk, in 2011.

Absolutely. Even before then, I think, you could hear some progress; some movement this way, but with The Devil’s Walk it was more noticeable. Before this album, I also worked on Moderat and this eased the change, I think. That’s one of the reasons I enjoy working as Moderat: the way we work is different to how I work as a solo artist and switching back and forth, from band to more nerdy stuff, keeps things fresh all the time. Even though it’s more exhausting, they ultimately both inform each other.

“I listened only to electronic music for like 10 years, and then I realised that there’s like this whole universe of post-rock and classical music, and suddenly electronic sounds became boring for me.”

— Apparat

How conscious was this move away from electronic music?

I don’t know how conscious it was. I had a traditional music education as a kid, and I wanted to be in a band, but it wasn’t easy for me so I didn’t actively pursue it. Then I discovered tehno at like 13, and I was like Fuck all this—why use a band when you have machines and you can DJ? I did this for 10 years, and I became so ignorant because I didn’t invest in other music. I listened only to electronic music for like 10 years, and then I realised that there’s like this whole universe of post-rock and classical music, and suddenly electronic sounds became boring for me.

Do you think you’ll ever go back to a more sound design approach?

I think during the last 10 years, when I wasn’t really interested in this sound craziness, that I kind of forgot how to do it. It’s gone, just like my Russian I learned in school, because I didn’t use it.

For the album, was it hard going back to solo work after years of working with Moderat?

It isn’t really solo work and, to be honest, I don’t think I can ever go back to solo work now. It feels like I can’t make a record on my own and that’s why I am always collaborating with people.

I am really open to taking about the music with them; it’s not like they’re ghost writers. It’s good to have someone you vibe with, and I always need someone to counterbalance my weaknesses. I am still good at producing and the nerdy stuff but I’ve never been a good player, so that’s why it’s important that I have Philip. He did night shifts and completely changed song ideas, and I came back the next day and continued to work with what he had done. I actually think Moderat taught me how to accept input like that; it made me more open to collaboration. A few years ago, I’d have suggested that we go back and erase everything he’d done, but this time I was really open to ideas.

That’s an important part of the creative process: taking a step back and looking at your work objectively.

Completely. That’s something that needs to be learned, especially if you grow up as an electronic musician, which is a solitary, artistic process. I come from a nerdy background and so I find this especially difficult.

Your music has been used a lot in television and film. Are visuals part of your writing process?

If I had done this interview 15 years ago, I would have told you that my processes are heavily based on visual aspects and the way I am using sequencers is like putting boxes in certain patterns, but it’s not like that anymore. I am barely looking at the sequencer; I mainly just play stuff and record. I think the reason that my music is “licence-friendly,” let’s say, is because of the moodiness of it, and these directors are always looking for a certain vibe, or something to create a certain vibe, and from time to time it seems like I have what they’re looking for. I am not doing this intentionally, but it did get me to the point where I wanted to begin making music for film.

“I think I’ve always lacked the ability to read crowds. With playing live, I’m the kind of performer who presents his music in the best possible way rather than trying to figure out what the crowd wants in this certain moment, and this has always worked for me. ”

— Apparat

How much are you composing for film nowadays?

I did a television movie a long time ago. I didn’t learn a lot; it was more adjusting music that I had already made to fit certain queues, but five years ago I realised I wanted to do it more. I wanted a playground where I am not a number one priority; where I have someone else’s instructions, because I think this is healthy. I also wanted to collaborate with someone who has a vision.

I found this Italian director and I did a film with him about a poet, and the film won an award at the Venice Film Festival. And we recently won a second prize for our second film together. I also won the David di Donatello award, the Italian version of an Oscar. I do enjoy doing this, but I also learned that you have to choose films carefully because I worked with an obsessive director once, and it was hard being tied to him for a year.

How hard is it to adapt your production methods for film?

It’s challenge. In the beginning, I remember being really overwhelmed and insecure. It was a case of learning by doing and now I feel comfortable; it’s about translating a feeling into music, and I’ve learned that the initial feeling is often right. This feeling only really came recently, which is cool because it allows me to work in a whole new world of music that is very different to where I started. I can do band shows, which is my job, and I can DJ, my hobby, and to mix it up I can do some film music.

Are you still DJing?

I do, and last year I had quite a few shows. I call it my hobby because I don’t consider myself a professional. I think I’ve always lacked the ability to read crowds. With playing live, I’m the kind of performer who presents his music in the best possible way rather than trying to figure out what the crowd wants in this certain moment, and this has always worked for me.

Has your experience writing for film informed your processes in writing for yourself?

Absolutely. Especially on the new record. I wanted to think some more on arrangements, and having some turns into directions you don’t normally expect. This is something that I learned in film scoring, where there isn’t the traditional structure: song, chorus, etc. I also took some parts I made for movies and shaped them into a song, even though they ended up differently as a result.

This transition in your production must have required that you transform your live set. How much of a challenge has this been?

That actually happened way earlier. I was playing band shows around 12 years ago, although they were pretty much public rehearsals; it took so long for these to actually sound like music!

It looks so easy when you see a great band on stage but the chemistry between people is not the easiest thing, especially when you remember I am not a trained musician. For The Devil’s Walk, we tried to play everything freely, without MIDI clocks, but we stuck way too much to the arrangements. With those theater shows, because we toured with this to seated audiences, we did everything much more freely and this was much less stress, and the concerts suddenly became better. With this new tour, we’re going to do that: we’re going to have the songs but we’re going to be much more free with it.

“To be able to be on stage with all these people in front of me, I’ve had to put myself in a bubble, and isolate and protect myself, not looking people in the eyes, because in that moment an anonymous mass becomes an individual, a person, and then I start over-thinking. That bubble has always included just me, and this gave me the security, but it disconnected me from the band because they weren’t in the bubble with me.”

— Apparat

Was it hard for you develop the confidence to let this flow?

Even though I’ve never been an extrovert on stage, this has never been the hard part. Going up there, being in front of people, has never been difficult for me; however, integrating myself in a group, and doing the right thing at the right time, has always been hard. You feel the music in a different way when you’re not connected with the people you’re on stage with, and it becomes a powerless set. I’ve had to learn to stay open.

To be able to be on stage with all these people in front of me, I’ve had to put myself in a bubble, and isolate and protect myself, not looking people in the eyes, because in that moment an anonymous mass becomes an individual, a person, and then I start over-thinking. That bubble has always included just me, and this gave me the security, but it disconnected me from the band because they weren’t in the bubble with me. So now, during the last few years, I’ve been learning to expand the bubble. In Moderat, it feels like it’s three of us in the bubble and now we have fun. Then, at some point, it doesn’t really matter what’s happening in front of you.

It feels like you’re in your own space with your mates.

Totally. It just happened recently actually. I think it was only on the last Moderat tour that we learned this. I was surprised at how different it felt.

It’s funny, because there are other people who really need that connection with the crowd.

Yes, like Nick Cave. He’s the complete opposite of what I am. I admire that. I will never become that sort of stage person but some people need that. It pushes them and gives them another energy.

You’re clearly learning a lot in your career. Are there still other avenues that you’re looking to explore?

I am still learning because I came into this career not knowing anything. I definitely want to get better at playing the piano because I think if you don’t then your motor memory kicks in and you just start to repeat the same patterns over and over again. I also want to understand the maths behind the keys, which will give me more space. I haven’t reached this stage yet, and perhaps people won’t like this—it can become a bit self-indulgent—but I am trying to achieve it through collaborations; by working with people who can do what I can’t.

Have you considered learning more instruments yourself?

Yes, I could totally do that. There is nobody pressuring me to release an album next year. I even wanted to do it this time, but at some point I just had my song ideas in an iTunes playlist and it clicks. I have 10 ideas and I get stuck to this playlist, and from this moment it’s hard to take time away; it feels like it needs to be finished.

“You have to trust your solo sounds, and that they can carry a song. I think back then I felt like the music was not enough, and that it needed more layers for it to be interesting, and I often buried interesting shit under unnecessary layers.”

— Apparat

Once you have this playlist, how does it work?

I’ll listen to it and work out what works and what doesn’t really work. I have to be bold enough to cut bits and throw them away. It’s funny, but this used to be hard. I was layering tracks; I often had 80 tracks playing in my sequencer at the same time, and it was a lot. Now, it’s a lot easier for me to throw away stuff; when Philip [Thimm] suggested we do it then I often did.

Would you then try to find something in a similar vibe, to fill the gap?

Very often there wasn’t a gap, even though you thought there was! You have to trust your solo sounds, and that they can carry a song. I think back then I felt like the music was not enough, and that it needed more layers for it to be interesting, and I often buried interesting shit under unnecessary layers. When I began preparing for the live performance, I went through the songs and I found stuff in the background that was really cool but nobody ever heard it because it was so far in the back, and I was trying to avoid that this time.

Do you think that’s a confidence thing?

That’s also definitely Moderat school. In Moderat, it happens often that you do something and someone comes into the room and says I love the idea, but…, and then the cleansing starts. You have to trust the other person, and once you do that, once you’re ok with someone throwing away your shit, then you get better at throwing your own shit away. The result is always better; that’s what I learned.

Are you mixing your work yourself?

I think I’ve reached a point where I have to mix my music myself, just because I’ve tried it with other people and it didn’t work as well. For this record, I noticed that my demos were close to what I wanted and then I had this skilled mixing engineer, Gareth Jones, who has to do exactly what I want. In his role, that would be me making film music for a director telling me exactly what he wants but he can’t because he’s not able to do it. It’s a waste of my talent in this moment, and I don’t want to use mixing engineers because I’m wasting their talents if I don’t let them do what they want to do. Even if I’m maybe not as skilled technically, I do reach the results that I want, but it just takes longer.

On top of it all, this is the fun part for me, which is crazy because sometimes I do 30 versions, and it starts being painful, and I become obsessed. I listen to half DBs that need to be changed here and there, and during the night I’ll listen on headphones and go back to the studio at 3am to do another mix because I don’t want to lose the feeling I have. That actually happened at Christmas this year and I made everyone completely crazy. I think this is just my personality, and I like this part a lot, and that’s reason alone to do it!

All photos: Nick Lapien