Artist Tips: re:ni

Career musings from the Timedance signee.

Artist Tips: re:ni

Career musings from the Timedance signee.

re:ni is the chosen alias of Lauren Bush, a Birmingham, England-born, Dorset-raised, and South London-based DJ-producer. Her musical roots stem from her father, a DJ himself who exposed his daughter to an array of records and hosted parties where he and his friends played sets incorporating soul, hip-hop, drum & bass, and house, among other genres. She found a connection to drum & bass soon thereafter, from partying and via her older friends in her orbit, and began DJing; encouraged by a friend, she bought a pair of decks and spent many months mixing her Dad’s old house records.

Over time, her sound has transitioned to a bass-heavy, rhythmic sound. A move to London has provided her with a steady stream of bookings across the UK and abroad. In 2018, she delivered an XLR8R podcast, a mix of dark and atmospheric rhythms spanning breakbeat, dub techno, and jungle, recorded live at Portugal’s Orbits Festival. A few years later, she released her debut EP, Revenge Body, on Munich’s Ilian Tape, and in February she put out her second outing, BeautySick on Batu‘s Timedance. Ahead of another hectic summer of touring, and in celebration of that release, she took a moment to reflect on the key things she’s learned over her career so far.

Take your time

When Revenge Body, my Ilian Tape record, came out in 2022, I immediately felt a pressure to follow it up; I really wanted to prove myself as a producer because I’d mainly been DJing up until that point and I wanted to show that I could also make good music. I was really proud of that record and I wanted to take advantage of the moment. When people rate what you’re doing it’s natural to want to keep bettering yourself and exceed their expectations.

After the pandemic, when I was touring regularly again, Batu approached me about working on a release on Timedance—something I was really excited about. But because I was playing so many gigs again, rather than being locked down at home, I found it nearly impossible to get back into a rhythm of writing tunes.

Looking back, I realise that my mindset switched; I found myself consumed by just getting stuff finished in the hope they’d be good enough to release rather than just enjoying making music. I was constantly second-guessing myself and putting unnecessary pressure on myself to be creative when I was exhausted from touring.

I later moved back to my parents for six months and something shifted again. I was once writing for fun, without the noise of London and I wasn’t thinking about timeframes and releases so much. Once I let go a bit and just went back to jamming and trying things out, I felt the creative block lift.

Two years passed, in fact. And, with hindsight, I’m so relieved I waited; during that time, my sound has continued to develop and I’ve now released a record I feel I will be happy with in years to come, which I don’t think I would have been had I rushed it. The tiniest details I added or subtracted in the final stages all contributed towards the end result.

I think you have to remind yourself of what you want from music. For me, I know that I want to listen back to my music and know that I executed it as best I could, and for this to happen I need every extra revision and tweak.

I think it’s especially important for me because my sound doesn’t easily fall into a singular genre; my tracks aren’t formulaic. I have to really think and consider what impact they’re going to have on the audience. On the dancefloor. Because I’m not following a pre-existing template or structure I think it takes me more time to get it right. To find the necessary nuance.

I recently unpacked my records after having them in storage and it was such a heartwarming process going through them: remembering where I first bought them, mixes and sets I’d played them in, generally just connecting with the music on a more visceral level. A record collection takes time to build; hours of digging, visiting record shops, practising for hours and hours. And it’s the same with producing. Finding your sound and style doesn’t happen overnight and developing your technique and style isn’t supposed to be easy or quick.

“There’s a great skill in knowing when you’re making tunes because you feel like you should, perhaps to try and please a label or someone, and when you’re making tunes because you feel inspired and you want to express yourself.”

—Re:ni

Don’t try to force creativity

As I mentioned, it can sometimes feel like external pressure or expectation takes away the joy of being creative. In these moments, it’s tempting to keep on pushing, but normally the tunes you’re making might have great elements but they won’t click. You’ll find yourself flogging a dead horse and that’s never a good place to be.

I’ve come to learn that there’s a great skill in knowing when you’re making tunes because you feel like you should, perhaps to try and please a label or someone, and when you’re making tunes because you feel inspired and you want to express yourself.

The best work is definitely in the second category. Your job is to stay there for as long as possible, and step away when you’re not in this zone. It’s not always easy to realise this but the first step is being conscious of it.

You have to remember you’re making music because it’s fulfilling for you, or whatever the initial reason you started producing was.

David Bowie talked about “never [playing] to the gallery”—”the reason you started was there was part of you inside that you wanted to manifest in order to understand better how you interact with the rest of society”—meaning making music was a way of understanding yourself better. Sometimes you need to stop trying, or stop all together and do something unrelated to making music, then come back to it, in order for it to make sense. Starting a remix can help because you’ve already got a framework and often new ideas stem from there.

I know when I’m not inspired because I’ll find myself being lazy. I’ll spend too much time on one idea simply to put myself off from starting something new. But I’ve learned from that.

Recently, for example, I was working on a 120 bpm sort of dubstep tune which I just couldn’t finish. I tried changing the tempo to 140 to see if that was the issue but it completely lost its groove and at that point I knew it was best to abandon it and move on.

That being said, you should always save projects because there might be elements of a tune which work perfectly in another context.

What I mean to say is this: it’s so important to jam and experiment in the studio rather than being focused on turning everything into an end product, however successful you are. Focus less on the end goal and more on the process. The enjoyment. That’s what you started doing this for in the first place, right?

Get comfortable with criticism but remember you’re making music for yourself

When I began releasing music in 2022, I really suffered from imposter syndrome and constantly worried that I wasn’t good enough.

One day I remember receiving an email from a label who was ready to sign a release having never even heard anything I’d made. I sort of had my suspicions that they just wanted a woman on their discography, to be honest. I know things have progressed a lot in terms of representation in this industry, but there are still labels and promoters out there looking to work with women solely to tick boxes and fill quotas, and when you have experiences like this it plays into the imposter syndrome feelings.

All this has shaped my attitude towards criticism, which can be difficult for artists to receive and absorb. I’ve come to value it, provided it’s constructive.

You grow so much out of feedback sessions with friends whose opinions you trust to be honest; and this is a tool that I encourage all artists to make use of. I actively seek it out.

It can crush you if you know they’re not feeling a tune, but you have to abandon your ego and remember people are being honest because they want you to improve and reach your full potential. (That is the people you trust anyway.)

That said, it’s important to use feedback to develop your own style rather than simply following someone else’s instruction. Keep an open mind, and don’t always do what your friends say. They aren’t always right. Because only you are you.

It’s about being open to other people’s takes and advice. But don’t try to make tunes that sound like theirs; instead, use their perspective to inform your own style.

I say this because when writing for someone else it’s easy to fixate on trying to please the label. To make music for them, rather than you. I spent months sweating over whether my tunes were going to be good enough and made it hell for myself.

Search for the balance between taking on board constructive criticism and buckling under the desire to please others. I’m inclined to put extra pressure on myself because of how many times I’ve been told by men I’ve only got certain opportunities for being female rather than being talented. It feels like the stakes are high, and that’s something I’m always fighting!

Nobody else can be you, so be yourself

I recently read an interview with DJ Spinn where he talks about authenticity. “The secret is always looking in the mirror and being better than yourself,” he said.

And it made me think.

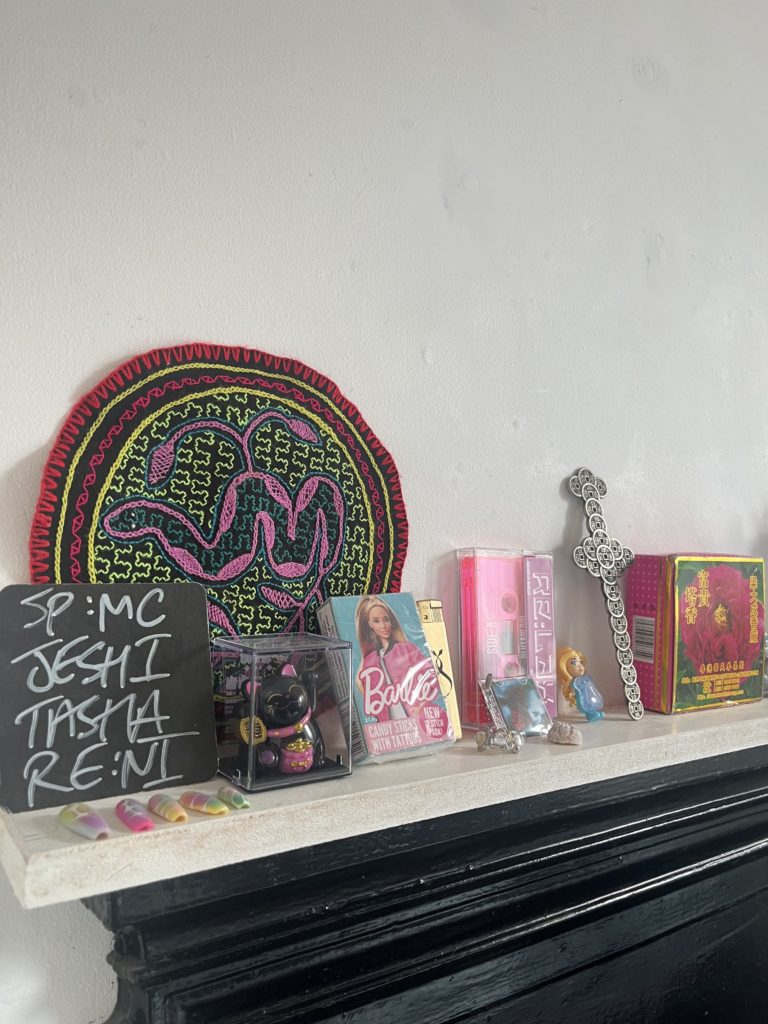

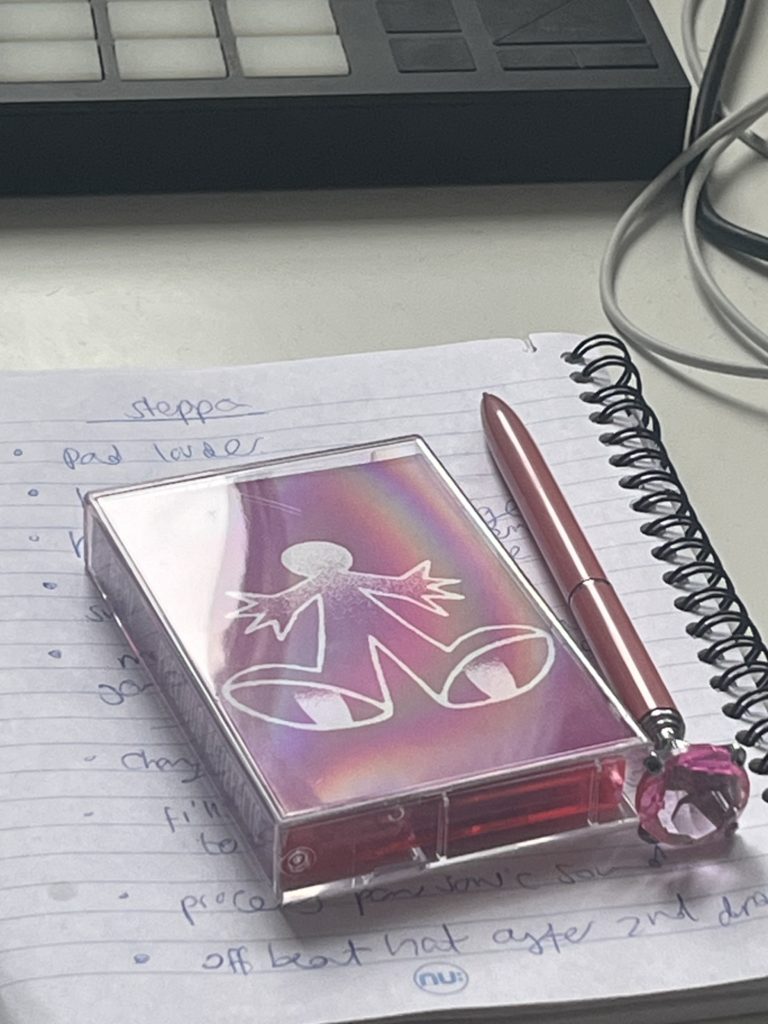

I feel like this process of finding authenticity in your music begins even before you open the DAW, in the environment you build around you. Having a home studio in a London flat isn’t particularly inspiring in my experience, so the more personal a space you can make it the better. I feel more creative when I have sentimental artefacts and trinkets around my decks and studio. It could an album or a book that inspires you. Somehow this has an effect on a subliminal level. I believe that.

I also think leaning into your emotions is a great idea. In can be really transformative because you’re making work that embodies whatever you’re going through at that time. Making music has definitely been a healing process and has brought me out of the trenches. In those low patches where interacting with people feels like too much, being creative can be a safe, cathartic space. When I listen back to those tunes now it’s a poignant experience.

As someone who has struggled with mental and physical health issues throughout my adult life I hope this might resonate with others and inspire someone reading to get creative; music and art really can be the best outlet for difficult emotions. Lean in, not away.

At least with DJing, there’s a lot more focus on the individual nowadays than there was pre-socials/pre-streamed content and it has created a pretty dire culture of social climbing and clout-chasing. I’ve spent one too many festivals bumping into DJs who don’t even acknowledge my friends if they’re not DJs or “in the industry.” Raving began as an escape: where you could be anonymous and enjoy this united transcendental experience regardless of anyone’s social status. It definitely feels like that’s got lost a bit.

In the age of social media there’s this pressure to be doing everything, to have your name everywhere, to be associated with certain people in order to further your career. It’s all very individualistic and at odds with the idea of dance music and raving as escapism.

I think you should do the opposite. Stay true to yourself and try to pay less attention to what everyone else is up to; being an online personality or part of a clique is not a genuine, and I doubt very fulfilling, path to success.

Elijah talks a lot about all of this on his socials and one thing he said stuck out to me recently: “You have to go outside to get it done.” My take on this is that you have to put the work in and go deeper than the surface level (i.e of social media clout) to have longevity and garner respect.

Focus on your strengths, but also your weaknesses

In the studio, it’s easy to focus on your strengths. That’s fun. Easy. But you should also develop your weaknesses.

For me, I’ve been DJing for years so arrangement is one of my strengths and comes naturally to me. Once I have a good idea I can fairly quickly build it into a playable structure.

What I find harder is mixing and getting sounds to sit together in a way that maximises their collective impact.

I feel like there’s a lot of comparisons you can make between making tunes and cooking. Where the drums and bass, which are a key part of mixing, are concerned I tend to think of them like baking where you need to be a bit more scientific and strict with amounts or it can all fall to pieces, as opposed to making a sauce or something where you can freestyle and there are no set rules.

I didn’t know any of these rules when I started out. Once I put reverb on my bass! All of it is a learning curve though.

When I’m making a track, I always remind myself that the kicks, bass, and snares are the parts I need to give the most attention to. They’re the core foundation of dance music and when you get those right you don’t need so many other sounds.

I spend a lot of time soloing out my drums, rejigging the patterns so they subtly change throughout the track, resampling and creatively processing one-shots of different percussion instruments that already feature in the track.

I’ll sometimes craft a really nice build or transition from just stretching out a snare hit, reversing it and adding a load of reverb and cutting it off right before the next beat in the bar. You’d traditionally think of pads and ambience providing atmosphere in music but I’ve learned that drums can do so much too.

I want to make music that leaves an impression on you on the dancefloor, which leads me onto another thing I’ve learned.

An important ingredient in this is restraint; being able to strike that balance between weirdness and functionality. I could spend all day playing around with vocals and delays, creating dubby soundscapes and so on, but without strong drums and a solid bassline, these elements swamp the groove of a track.

I’ve been working hard to understand this balance, and how it all fits together. Where does it make sense for a section of a track to be dry and stripped back in order to create contrast and make the trippy parts more impactful?

To do this I remind myself to experiment. To not always make music that I’m going to share with other people.

This is linked to what I said before. Instead of trying to finish tunes, it can be a lot more productive in the long run to spend time just experimenting. There’s so much to learn in terms of layering and EQing and that’s before even getting to processing, where you can be endlessly creative.

On “BURSTTRAP,” for example, I wanted to try something different where the bass was more of a lead, as I tend to go for simple sine subs that are less of the main character. I created a more stereo sound with a phaser and duplicated with a drier version, and although the tune grew into a lot more as I added vocals as a main feature, it was built around the bassline which isn’t usually how I write. I mention it here because making this tune definitely showed me it’s well worth mixing up your process!

Actively practise good habits

This tip refers specifically to DJing rather than production.

When it comes to learning an instrument or a sport, the phrase “practise makes perfect'” has been the gospel. But I don’t think this theory is watertight: through the process of repetition, something becomes a habit, and this also means that bad habits can linger. “Practice makes permanent” is more accurate.

I don’t often bring records to gigs anymore but I play them at home a lot, for fun but also to practise beat-matching and phrasing without the visual cues of CDJs. That’s because I think it’s always good to have a more challenging home set-up so that you’re better equipped to deal with potentially unfamiliar or challenging settings when it comes to playing out.

I read an interview with DJ Bone where he talked about his first home DJ set up being like a bootcamp, preparing him for every possible variable where he might have to adapt so when it came to club shows he was hardy and prepared for anything.

You really have to go into gigs being prepared to adapt, because every club set up isn’t going to be the same and it definitely won’t feel as comfortable as playing from your bedroom. Yes, it’s frustrating when you encounter technical difficulties, for example you play a show and there’s an issue with the monitors or you’re playing b2b with someone who might play in a very different style to you. It feels like you can’t go into autopilot as you would playing at home or solo. But this is all part of being a better DJ; you adapt and learn from mistakes. And by being smart with your home setup, you can make yourself more adaptable.

Photos: Artist’s own