Cabanne: Accidents of Life

The French minimal pioneer finally reveals his tale and reflects on his jazz-infused debut LP.

Cabanne: Accidents of Life

The French minimal pioneer finally reveals his tale and reflects on his jazz-infused debut LP.

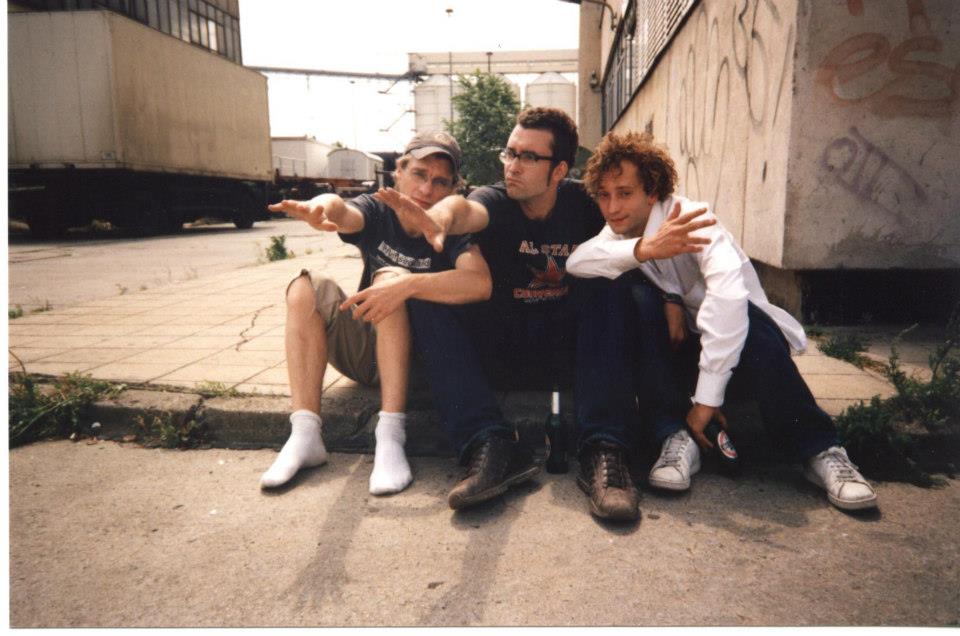

Touring frequently and releasing on some of the scene’s most lauded imprints, it’s no surprise that Jean-Guillaume Cabanne has established himself as one of minimal’s leading names. So deep that he has become in the electronic realm that it’s easy to overlook that he’s a musician at heart, one with deep roots in jazz, funk and everything in between. His latest release, however—a wonderful debut album, for that matter—sees him revisit these former pastures for the first time, in effect sharing a side of his musical heritage of which only very few of his fans were even aware. Naturally intrigued by the LP, William Ralston traveled to Paris to learn more about the untold tale behind it.

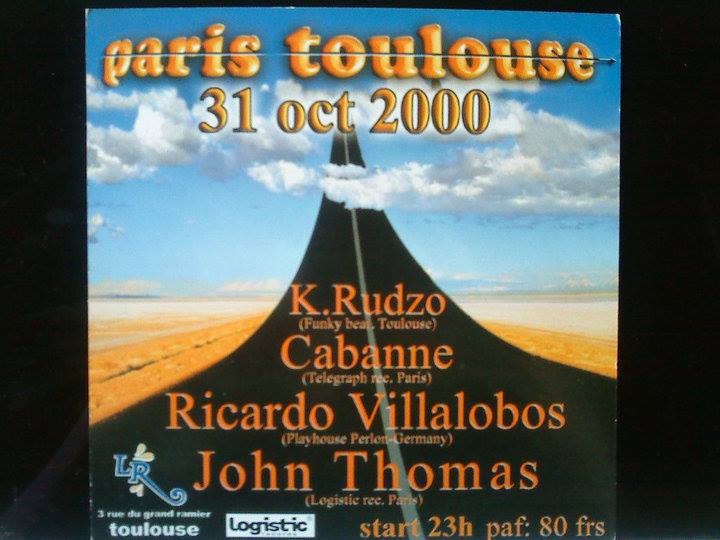

Almost 20 years have passed since Jean-Guillaume Cabanne’s name first appeared on an electronic music record. The cut, a downtempo effort alongside France’s John Thomas, arrived in 1997 as part of the four-track various artist EP on Logistic Records—the opening page of a musical catalog that now boasts close to 20 solo EPs and multiple others in collaboration with trusted artist friends. This collection, Cabanne explains, is one that he reflects upon with great pride, but also one that has long been marred by the glaring omission of an album. “I come from regular soul, jazz and funk styles where an LP is a rite of passage,” he explains. “I’ve been trying to do it for 10 years—but I’ve just continued to push it back.” Now, having chipped away for the best part of a decade, the Paris-based DJ-producer has completed his much anticipated debut LP, released via his own Minibar imprint just last week.

Discopathy is likely to surprise many of those who have followed Cabanne’s releases. It’s difficult to imagine any of the tracks fitting comfortably on any of his EPs; indeed, only three would come anywhere close. Included instead are various works of jazz, soul and funk, a stark contrast to the the groovy micro-house sound with which he has become so strongly affiliated.

Of course, it’s not uncommon for electronic artists to distance themselves from the dancefloor as they explore longer formats, but Cabanne’s reasoning stems from a diverse musical background as much as a desire to produce something more conceptual. “I’ve been training as a musician all my life,” he explains, grinning while rooting around the pockets of his green khaki shorts in search of the tobacco needed to roll yet another joint. Then, focusing—a contrast to the tongue-in-cheek tone on show during many of our earlier exchanges—as he settles on the sofa freed from the shackles of addiction, he explains that EPs are a continued source of frustration because they do allow him the to present the various sides of his musical background.“I can do funk; I can do hip-hop; I can do soul—and I want to connect all of these sub-genres,” he adds. In this sense, Discopathy serves as a “prism”: “It’s more about revealing where I could go musically and what I’ve been through over the last 15 years rather than where I am now,” he continues. “I could soon start doing funk and soul, or even begin playing the guitar a lot more than the decks. Who knows?”

“Of course my personality has limited my growth. But you have to deal with what you have.”

In truth, little is known about these influences to which he refers, and even less is known about the man himself. His affiliations with Logistic, Telegraph, Perlon and Minibar remain no secret, but Cabanne’s character has long been one shrouded in mystery; his image based on rumour rather than documentation. Followers of micro-house will almost certainly have seen him play—alongside his residency at Paris’ Concrete and Berlin’s CDV, he’s also a regular guest at Get Perlonized events and performs frequently throughout Europe—or be familiar with his productions, but he remains distanced from the spotlight as something of a polarising figure. While there is certainly no shortage of Cabanne admirers, you wouldn’t have to look too far to find those who question his commitment to digging for new records or even criticise elements of his studio output. Above all, his reluctance to “play the game” has created something of a tainted profile, a trait that he confesses has stunted his success. “Of course my personality has limited my growth,” he says. “But you have to deal with what you have.”

The Cabanne story is not an easy one to tell. Not only is it lengthy and intricate, but included within are several sensitive incidents that are not pleasant to revisit. The collective term for these, Cabanne explains, is “accidents of life,” all of which have led him onto the path that he walks proudly along today. It is partly for these reasons that he has chosen not to divulge his past on any previous occasion; it’s also not in his nature to seek unnecessary attention. His work has never placed him in the limelight and it’s unlikely that it ever will—it’s also clear that he does not wish it to. But this debut album, he adds, is a milestone in his career and should be perceived as an encapsulation of all that has unfolded before. It seemed, he says, only fitting that his tale now be uncovered.

Cabanne spent his earliest years in Brétignolles sur Mer, a modest seaside village on the western coast of France. It was an “easy” childhood until the age of eight when his father’s life was taken in a bike accident—a “real killer,” he says, that made him see life “very differently.” A swift relocation then ensued: in need of support raising her three children—and partly in search of gainful employment—Cabanne’s mother moved the family to Dijon, the city in eastern France from which her husband originated. “She thought it would help us all to be closer to my father’s family and also join the same school that he had attended,” Cabanne recalls. It was during this six-year period that he discovered a “special connection” with music through Gregorian chant, before being expelled for misbehaving. “I was a hyperactive bad boy as a kid,” he says. “My father had died and I needed to find new ways to express myself.” With a shortage of tolerating educational institutions in the area, the next stop was Henry Bergson college in Garches, a commune on the outskirts of western Paris where he learned the guitar and started The Wigs, his first band project—at the age of 14.

His interest in electronic music only began after he met David Gluck when they both attended Florent Schmitt high school. “He was the one who started it all,” Cabanne explains, pointing out that the two would never have crossed paths were it not for his family’s earlier move to Dijon, itself a consequence of his father’s accident. Gluck—Cabanne’s partner in Ultrakurt—was into the party scene at the time, and it didn’t take long for the two to begin learning the basics of music production both aged 17—although Cabanne’s commitment to various other band projects limited the amount of time he could focus on this endeavor.

The unfortunate turning point came in December 1992. The plan, as it stood, was for Cabanne and his best friend Thomas Cante to begin a rock band together—and both were soon due to enrol at the American School of Modern Music, one of the finest Parisian institutions for jazz theory. But this all changed when Cante was killed in a motorcycle accident, a replica of that which took the life of Cabanne’s father around 10 years earlier. “It broke my fucking head,” Cabanne recalls. “I struggled to go to class because everything reminded me of him.” Given that he and Cante had shared ambitions of becoming full-time musicians, Cabanne made the decision to quit all studies besides those that fitted in with these intentions.“I knew then that I could only do music,” he says. “It was the only thing that I had left.” He was 18 at the time.

“If Thomas [Cante] hadn’t have died then maybe I would be still be playing rock and roll or jazz—who knows? But for sure I would not have arrived so quickly into electronic music; I would have resisted the call by claiming that I am a musician or something else like this.”

Cabanne’s relationship with electronic music grew following Cante’s passing. Raving, he explains, became an increasingly important outlet, a form of escapism from the pain within. In addition to this, he grew closer to Gluck, an early follower of the scene; and it was only natural that his knowledge in the field grew too. “If Thomas [Cante] hadn’t have died then maybe I would be still be playing rock and roll or jazz—who knows?” he continues. “But for sure I would not have arrived so quickly into electronic music; I would have resisted the call by claiming that I am a musician or something else like this.” It wasn’t long before he and Gluck began partying with regularity.

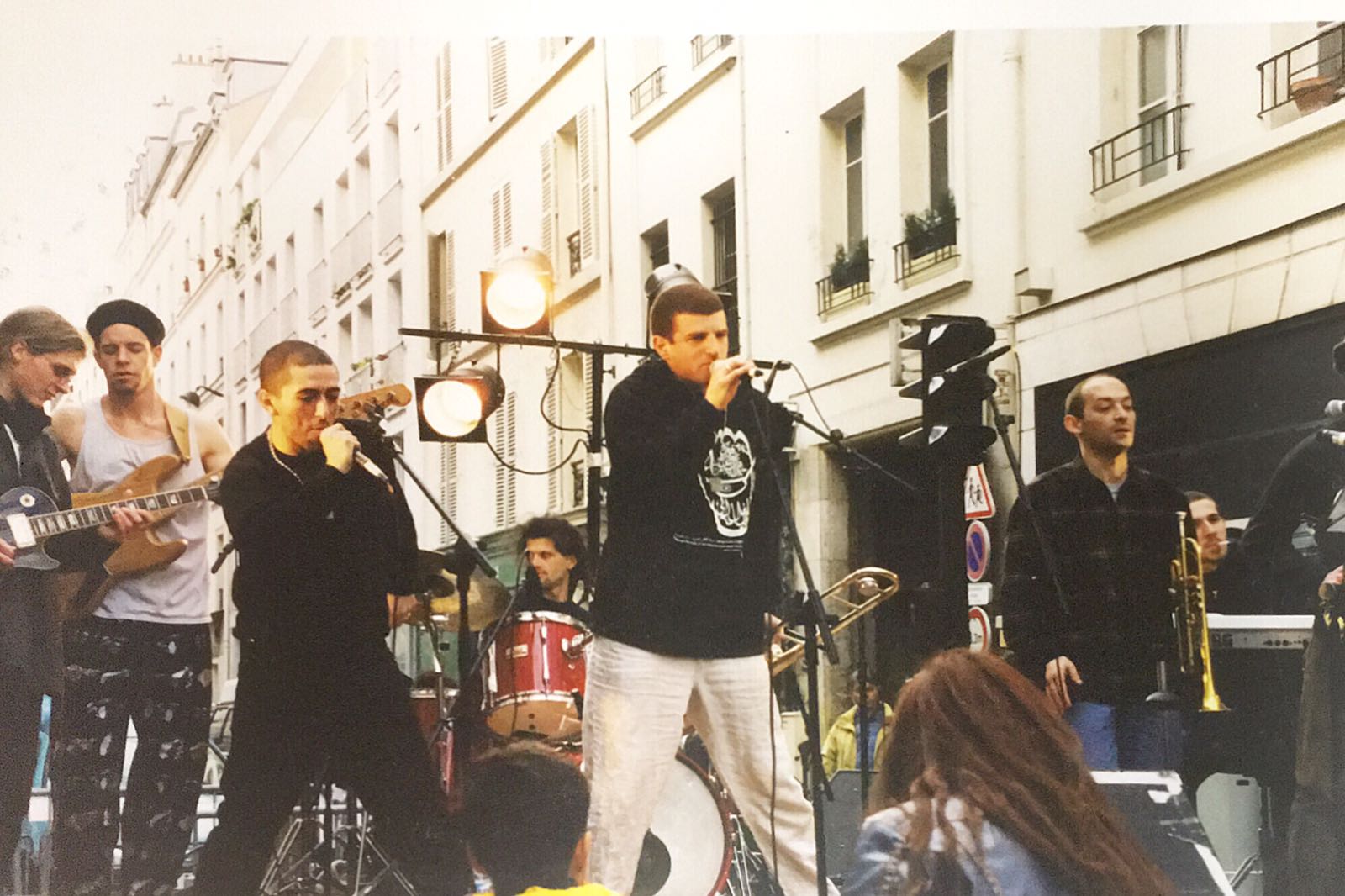

It was a similar misfortune that sparked an interest in electronic production. Driven by a “compulsion” to succeed as a musician, Cabanne filled his four-year spell at the American School with various bands outside of his studies. The most notable of these were F.L.A.G (Front de Liberation Autonomiste du Groove), a nine-member funk project; and Chaotik Ramses, a collaborative trip-hop duo with several releases on Laurent Garnier’s F Communications. He also worked with Master-H on a remix project for Warner Music—“the first time I came across an 808 was when Master-H left it at my house,” Cabanne recalls, laughing. When tendonitis formed in his elbow, however—a result of playing the guitar for over eight hours each day—he was forced to explore other avenues of practice. His first step was the purchase of an Atari in order to revise the chords, but it was through the same machine that he learned the basics of electronic programming. “I became very geeky about production at this time,” he recalls. Soon, he and Gluck began experimenting with various synthesisers—and Cabanne the electronic producer was born.

The results of these various projects and also a growing affiliation with the Parisian nightlife scene were chance meetings with Ark and John Thomas, the “little star of the French techno movement.” Jeff Lasson, the bass player in F.L.A.G, who also worked with Cabanne on the Keith Mash collaboration, happened to be close friends with Ark—a guitarist himself—and called him to fill in for Cabanne on the two occasions that Cabanne was tied up with Chaotik Ramses. Naturally, Cabanne’s relationships with Ark developed following this introduction. “It was a small scene,” he recalls.

As for Thomas: upon discovering a shared appreciation for music—“He saw me playing guitar and realised I was a musician too,” Cabanne says—the duo committed to some studio time together, the first result of which was 1998’s “Harmonic” on Logistic Records. And it wasn’t long before the techno-focused imprint became Cabanne’s “home,” thereby completing his transition from the jazz and acoustic realms. “The guys [at Logistic] loved the music I was making with John [Thomas],” Cabanne recalls. ”We all became close friends. It was more of a family thing.”

Soon thereafter, Cabanne began focusing on his first solo material, while also working with Thomas on their collaboration—including 2001’s six-track Blackstage album. All studio work was balanced with classes at CIM, a two-day-per-week Parisian jazz school that placed particular emphasis on improvisation—although Cabanne subsequently dropped out in 1998 at the age of just 25, after just two years. The reason, he explains, was simple: due to the loss of his father, the government covered all education fees up until this age so he had kept up studies only to keep his mother happy—an easy commitment given that the course was not particularly intense. Sufficient income was already being drawn from various other musical endeavours by this point.

DJing, too, soon became a point of focus. It was, he explains, a skill at which he had been competent for many years having learned “easily” while on holiday with his girlfriend in 1995. “A friend brought turntables so I tried to pitch the records,” he recalls. “And within five minutes I could do it. Everyone began to look at me, and I started to have fun with it,” he adds. “But I think it’s a lot easier as a musician.” Initial bookings were all in Paris and the surroundings areas before his first international gig came in Zurich on New Years Eve 2000 for Thomas Brinkmann.

His DJing has, of course, taken centre stage since then; indeed, it could be argued that Cabanne is now more widely considered a selector rather than a producer. And it’s easy to understand the source of these successes: not only is he one of the finest in terms of technical proficiency—you don’t really see him mix badly unless there are issues with the setup or he is “too stoned,” he jokes—but those who have seen him play will likely have appreciated the incessant groove. “People always say that you can hear that I am a musician when I play,” he says. In many ways, he’s carved out his own micro-house soundscape in a heavily saturated niche. The reason for this stems not only from the records he chooses but also the way he mixes them: “When you have two records you have one, two, three, four on one and one, two, three, four on the other,” he explains. “I will always mix two and four together—which is on the snare or the clap; I never pitch on the bass drum or on the hi hats,” he continues. “That doesn’t make me technically better than other DJs, but this is where the groove comes from.”

“For me there is no challenge in mixing records. The hard part for me is making a good trip or a story.”

However, as innately skilled as one may be at mixing one track with another, DJing requires a considerable investment of time to learn how to construct a compelling set. And, although invariably a source of entertainment with the impeccable mixing and irresistible groove, Cabanne explains his ongoing struggles with the creation of a narrative that is so fundamental in the formulation of those rare musical moments that dwell in the mind after completion. “For me there is no challenge in mixing records,” he says. “The hard part for me is making a good trip or a story.”

Much of this, Cabanne explains, comes down to mindset: “Sometimes I am a bit sterile because I can struggle with this lifestyle,” he says, candidly. “I have been living from DJing for a long time because I don’t have any other way.” He goes on to describe travel as a “necessary sacrifice” that allows him to make a living from music—an exaggeration, he stresses, but one that reflects his mindset when he spends weekends waiting in any number of Europe’s airport terminals. “Sometimes I’d really like to stay in the studio and make music,” he adds. “I have always been into the geeky side of music—that’s the side that has always interested me. I was a guitar player so the step to becoming a DJ was not so natural.” While he confesses to enjoying playing records in a club, DJing and the associated travel is something he can do rather than loves doing, and it’s only natural that this is sometimes reflected in his work.

That being said, Cabanne points out that he remains dedicated to his work—at least when it comes to collecting records. I’ve heard it said previously that he is a “lazy digger,” but this feels more of an illusion based on his slender sound aesthetic. He’s been digging since the age of 12, and his collection today consists of over 6,500 vinyls and 800 CDs—the genres of which span “many different styles,” he says. “I don’t even have a TV because all my life is about listening and playing music. It has been that way since I was 10 years old.” It’s inevitable that at any given time there will be certain recognisable records that become staples in sets of many of the leading artists for the months around their release—but this is a trap into which Cabanne does not regularly tumble; instead, Cabanne sets are laced with obscure cuts that fit his own style and are rarely played out by his peers.

“A lot of people pick their records based on the fact that somebody else is playing it, but it’s important to do what you want.”

The reason for this, he explains, is result of how he shops—a task he undertakes for “one whole day in every two-week period.” Starting on Juno, he will not just look at his favorite the labels and artists; rather “if there are 800 new records then I will listen to 800 new records,” he says. Linked to this is his choice of format: Cabanne is an almost exclusively vinyl DJ; rarely will you catch him reaching for the CDJ. Consequently, he avoids the temptation to play the records of his peers. “Everyone shares everything in the digital world and so everybody ends up playing the same,” he continues. “A lot of people pick their records based on the fact that somebody else is playing it, but it’s important to do what you want.” This, he adds, is why he refrains from using Discogs and doesn’t watch other artists play to pick out tracks that he likes.

Production, however, will forever remain the object of Cabanne’s affections—and this is where the tale continues with Telegraph. The role of the sub-label, of course, is already known: encouraged by John Thomas—who was “crazy” about Cabanne’s work—the figures behind Logistic formed Telegraph in 1999 as a home for the micro-house productions originating from Cabanne’s Paris studio. This music was “completely different” to that of Logistic and would only have diluted its sound aesthetic. “At the time, techno was about 130 BPM, but I was doing around 125 so we were in a warmer sub-genre,” Cabanne says—a result, he continues, of his main influences, namely Matthew Herbert, Ark, Dimbiman, Daniel Bell, and Ricardo Villalobos. 2000 saw Cabanne’s first Telegraph release, a four-tracker entitled L’Euphorie Des Glandeurs; this was followed with four more EPs before he was pushed out of the imprint in 2003 for various “bad” reasons.

Telegraph/Logistic’s growth over these years, of course, marked the start of an exciting movement in the Parisian music scene. “It was like two families,” Cabanne recalls, referring to the synergy with the Karat/Katapult crew that helped promote this minimal sound in the city. Karat, the label arm of the Katapult record store, popped up and worked closely with those behind Telegraph/Logistic to promote this sub-genre, throwing parties and festivals while inviting key labels from abroad, including the likes of Playhouse and Perlon. Cabanne became something a central figure in this movement, playing regularly at the events and releasing on the accompanying labels. “This brought the sound to Paris,” he adds. Much of this work has now been continued by Concrete, the widely known booking agency/label by which Cabanne has been represented since its 2011 beginnings.

The next “accident” occurred around the same time; the result was Cabanne’s 2002 Can’t Stand three-tracker on 7th City. The story goes like this: Cabanne’s 2000 Au Canada release dropped via Telegraph at the moment John Thomas’ Funkless #2 arrived on Logistic. However, several copies of the former were mistakenly distributed with the labels of the latter, leading Daniel Bell—an avid follower of Thomas’ work—to contact those behind the labels to query just what had inspired Thomas to “change his style so much,” Cabanne recalls. On discovering the real artist behind these impressive productions, Bell then invited Cabanne to release on his label, kick starting the friendship that they continue to share today. “This was a huge thing for me,” Cabanne explains. “Because it was a Frenchman releasing on a Detroit label.” Rare double-stamped copies of the Au Canada EP remain in circulation.

Although a temporary affair, the importance of Telegraph must not be overlooked. The challenges faced by aspiring producers are documented, and Cabanne owes much his success to the label. Despite a wealth of experience, Cabanne explains that he will “never be confident with his music” and will always “struggle” to share it with others—something that he stresses remained true with the LP. Telegraph allowed him to put out his music “free of complications of judgement.” He describes releasing as a form of “sickness”: as challenging as he finds it, it’s something he must do to for his own validation. “I need my own label to put my records out because otherwise I would never be able to share them,” he adds. Indeed, it was for this reason that he started Minibar in 2005. “I didn’t have Telegraph anymore and I needed somewhere to release my music,” he says. “It’s very simple.” The vinyl-only label was founded alongside Eric Vence and is still in operation today. Besides the work of Cabanne and several others of the French contingent, the imprint houses productions from various other international artists.

![Narod Niki [ Left to right: Richie Hawtin, Akufen, Ricardo Villalobos, Zip, Dandy Jack, Luciano, Cabanne, Daniel Bell] at Mutek Montreal 2003.](https://xlr8r.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/narod.jpg)

And it was also these early Telegraph releases that opened the door to Perlon, the renowned imprint with which Cabanne has held close ties since 2001. Having purchased Ricardo Villalobos’ Ibiza ’99 record, Cabanne suggested that Logistic should invited the famed Chilean over for a party—even though they “didn’t really know who he was.” This was a time when there was “no real audience” for this style of music, meaning it was actually the first time Villalobos had performed in France. Cabanne, he continues, had long been a fan of Playhouse and Perlon and asked Villalobos if he could be considered for a release on either imprint.“He told me that Playhouse was locked but that Zip was his friend and the Perlon guys loved my records,” Cabanne explains, grinning again. Villalobos then passed a CD onto Zip who subsequently invited Cabanne to release 2001’s Copacabannark—a split EP with Ark—on the label. 2004 then saw the same duo return with a collaborative five-tracker, titled To Beach Or Not To Beach. The Copacabannark collaboration was actually born from Zip’s mind.

At Mutek Montreal in 2003, Cabanne went on to perform in laptop supergroup Narod Niki, a fully improvised live act of which the participants would continually switch in and out. By his side at Mutek were Ricardo Villalobos, Zip, Akufen, Richie Hawtin, Luciano, Dan Bell, and Dandy Jack. Robert Henke, one of the creators of Ableton live, loved the idea so much that he came to be the one at the mixer. It was entirely unscheduled, occurring only because all members were there on site as individual artists. They didn’t even have a chance to rehearse: “We were supposed to have one session to prepare for it but the guys never came to open the place,” Cabanne recalls. “At one stage we were all waiting in the street for one hour before realizing that we were going to have to improvise it all without synchronisation!” Narod Niki went on to perform on two more occasions, and there was a secret cut on the second Telegraph compilation.

“I wish I had more time in the studio. This is my biggest shit in life.”

It’s an interesting position in which Cabanne finds himself. As a core member of the Concrete roster—his studio is situated below the Paris headquarters—with a reliable influx of booking requests, he’s achieved his objective of making a good living as a musician. Indeed, on several occasions he stresses that the “widespread recognition” he has now is sufficient recompense for his efforts, and denies the existence of a grander vision at large. “I don’t wish to be somewhere else so I think I have probably reached my goal,” he says. “I could wish to have bigger fees but if I am true to myself I know I am not playing the music that earn these features. I cannot wish for something that I am not working for.” Yet, as grateful as he is for his success—as happy as he is that he is able to earn a living from music without compromising himself—there is a growing desire for more time in the studio to continue refining his work of the past decade. “I wish I had more time in the studio. This is my biggest shit in life,” he adds. “I love just waking up in the morning and just messing around in the studio. I don’t care what is happening outside or inside: I just care about what is happening in that room.”

Discopathy, for those of you who have listened, reveals a certain musicality that can appear absent in an electronic scene that so often favours function over form—it’s also one that has not been commonly associated with Cabanne over the course of his career. For this reason alone, it’ll most probably have come as a surprise—but it’s likely to be a welcome one for music lovers who give it some time and harbour tastes that transcend the confines of the dancefloor. And it will be, Cabanne insists, the first of many: looking forward, he reveals plans to make changes to allow himself more studio time and also stresses that technological advancements will allow him to better incorporate his music training into his production.

That being said, he remains open as to how these future LPs will sound.

After all, he says, “I am a real musician at heart.”

Support Independent Media

Music, in-depth features, artist content (sample packs, project files, mix downloads), news, and art, for only $3.99/month.