In the Studio: Tobi Neumann

XLR8R spends an afternoon at Riverside Studios with a staple of the German electronic scene.

In the Studio: Tobi Neumann

XLR8R spends an afternoon at Riverside Studios with a staple of the German electronic scene.

Having working previously as a composer for jingles and commercials, and with numerous collaborations with artists on the front line of electronic music under his belt, Tobi Neumann makes a perfect conversation partner for an in depth ‘In The Studio’ talk. Having placed himself on the map with his productions for Chicks on Speed in 1998, he has become a driving force in the German house and electro scene, known both for his productions for artists such as Miss Kittin and 2Raumwohnung and his DJ sets as a part of Sven Väth’s Cocoon. His latest collaboration with Marco Unzip, under the name ToCo, serves as a perfect demonstration of his musical talents, his affection for modular, and his productional capabilities.

We visit Tobi Neumann in his Berlin studio, a part of the Riverside Studio complex situated between Köpenicker Strasse and the Spree. It is a breeding ground for music, a place where one hears a diverse palette of sounds just walking through the corridors; one where collaborative projects like Pan-Pot and Booka Shade are just one sound-proofed wall away. We talk to Tobi about the path he travelled to get to where is he is now, covering topics of a technical, musical and more personal nature.

Tobi, you have an interesting track record. Can you tell us something about your work and education, leading up to your career as a DJ-producer?

Originally I studied Sound for Film; this was in the time before ProTools even existed. We did everything with tape machines that used tape reels with perforation holes, either in 35, 19 or 16 mm. They were the same perforation holes as used on film, so synchronisation was guaranteed by a mechanical system which used the holes a grid. Then I started to work for a Sound Engineer for television, and I started to invest my earned money in the studio.

When did you start making your own productions, rather than working on commission?

In the late ‘80s I shared a flat with Tommi Eckart from 2Raumwohnung and we had our first kind of studio together. We had the S440 from Sequential Circuits which was similar to the AKAI MPC, and Roland‘s S550, which was a 12-bit sampler with a monitor and a quite a futuristic screen, and a mouse to operate the sampler. The sampler itself didn’t sound very good, and it had super bad MIDI timing. And we worked with Ataris. I had the studio with him until 1991, from 1986, and then I moved into my own flat.

What kind of music were you making at this time?

We were just trying it out. I remember we were listening to some house records and we tried to sound similar. Tommy had a couple of 303s and later a 909. We tried to work with a hardware sequencer but the main groove was coming from the machines. Besides that I did a lot of film music and music for advertisements, and I tried to record bands—that was super frustrating because, especially when you record with microphones, you need the perfect rooms and professional gear. Honestly I wasn’t making the progress I wanted to have until I started with electronic music. It felt natural to me and therefore it made more sense for me to set up something in this field.

“If I think about it, between my 14th and 18th birthdays, back in the ’70s and early ’80s, when we were doing house parties I always played the music! DJs didn’t exist, but I needed to do it. Already at this time, there was something. I wanted to make people move!”

How did you first discover this music?

I first just got in touch with it through Tommi, because he came back from NY in 1988/1989 and he was totally crazy about house music. We didn’t even know what house music was at that time, but we tried to copy the sound. I was doing a lot of other projects at the same time, but in the middle of the ‘90s the impact of house and techno became really big.

Did your visit of the Loveparade in 1995 have to do with this?

Yes, ’95 and ’96. 1996 was the year that we really partied. I was 30 at the time.

Was this an important moment in your career?

Yeah, it was the main trigger to start buying vinyl, to start playing and to do my own party. Things happened really fast in the beginning. I started my own party, called Flokati House Club at the Ultraschall in Munich, which was the place to be for techno in Munich at the time. The party was a big success, and that’s where I learned the trade: doing opening sets and making people move.

Before then were you DJing?

I was working as a sound engineer, but I wasn’t really DJing. If I think about it, between my 14th and 18th birthdays, back in the ’70s and early ’80s, when we were doing house parties I always played the music! DJs didn’t exist, but I needed to do it. Already at this time, there was something. I wanted to make people move!

You mentioned the setup you had in your first studio, together with Tommi Eckard. Was that the studio in which you produced you first electronic records?

No. The first record I did in this genre, the first dancefloor-oriented record, was “Warm Letherette” with Chicks on Speed. It was released in 1998, and came out on a 7”. It was a remake of Daniel Miller’s classic track, released under the alias The Normal. We did a new version of it and it had a huge impact on the scene. There was a second record too, called “Euro Trash Girl.” Before that, I was already used to working with loops, samples and synthesizers for my work as a composer for jingles and television.

Also the music I made prior to that with my partner Peter Horn was also heavily based on grooves and repetitive rhythmic structures. So, I was somehow ready when the ‘Chicks’ came along. I met Chicks on Speed at Ultraschall and I told them, “I have a studio, why don’t we just record a record?” We did the first two tracks together, and I don’t know what happened but it suddenly really took off.

What was the setup you used for these early tracks?

I had a Roland 808, a 909, an S3200 and later this E-MU sampler. I think the first sound program I made was even called ‘Chicks,’ which I still use a lot these days. Besides that I had a Soundcraft mixer and some Lexicon units. I cannot live in a studio without Lexicon small room reverbs for breathing life into a dull mix. Besides that I used a delay unit, the Lexicon PCM42, and an Apple computer with Logic. However, we recorded everything on DAT. I recently started doing this again, because often the 16-bit sounds much better than modern techniques.

Here is a tip that I can give to the readers and the followers of the magazine: E-MU E4 Ultra, buy them used because the sound is absolutely unique. There is no software sampler in the world that can bring the sound in front of the mix as well as these old 16-bit sampling engines. It is absolutely unbelievable how they sound. Also, the functionality of the E-MU’s EUS software, with the routings, is incredible.

“For me, making my own music is much harder than producing for other people, or doing mix-downs. Now, I even ask for outside help when it comes to my projects. I have never really made that much music under my own name because I have always been too critical, and I often really didn’t like what I did!”

Even back then, did the mixer have an important role in your studio?

Yes, I really love to touch the mixer while I’m working on a mix-down. In the mix process I really like to mix in effects on the fly, make a couple of versions, and then cut them together. I just love to intuitively let things happen during the mixing session. I’ve been DJing for 15 years, so I’ve been touching knobs for a long time, so why not use this experience in the mix-down process?

You appear to be quiet a perfectionist when it comes to mix-downs, but, at the same time you say that you have to let it go, at some point. Is it hard for you to find that moment?

Yes, I experience this mostly with my own music. For me, making my own music is much harder than producing for other people, or doing mix-downs. Now, I even ask for outside help when it comes to my projects. I have never really made that much music under my own name because I have always been too critical, and I often really didn’t like what I did!

Now, I seem to have found a way to make it work. The machines are running freely, there are no small loops, no small cycles anymore on the computer. I record long jam sessions with the Modular in Ableton or Logic, and make edits of the material after. This way I have found a way to once again make music by myself and let things develop—just like in the times that we were playing in bands, in jam sessions. I find that working too much within ‘bars’ really takes away my inspiration.

Why is it harder for you to finish your own music? Does it feel more personal?

It is because I am a DJ and so I am always surrounded by the best music, the hottest shit—the latest stuff. All these promo agencies send you the most sophisticated new developments in electronic music and you automatically start to compare it with your own stuff.

We all know that there is always a time in which you hit the right nerve with your music, but this ends after a while. And then you either have to rely on your own tradition of sound, for example Mark Broom with 20 years of incredible music, Floorplan or Ricardo Villalobos. These kind of people that have a very distinct sound that they stand for. When you compare your own material too much with other stuff, then your inspiration can suffer. So, in a way, it’s better not to be online to much; it’s somehow better not to listen too much to what others are doing. But this is against DJing, because DJing is doing exactly that: intensively looking for other people’s music. And honestly, this has given me a couple of problems!

So DJing actually impedes your work in the studio, and vice versa too?

Exactly. DJing during the weekend after being in the studio all week is really hard for me. Switching between the two worlds is not easy. For example, this weekend, I will be playing a show after two weeks of studio work. I still want to do music but I have to switch to DJ-mode to prepare myself, and this takes at least one day. Taking records from my shelf, finding some new digital promos, going to the record shop, buying tracks on Beatport or Tracksource. I’ve got to sharpen the knives!

Do you feel that studio work is something more introverted, compared to DJing at least?

Yes! You don’t even have to be presentable during; you don’t need to cut your hair and you might come home with a patch cable still around your neck! And, then you go the next day and have to DJ. But you know, I am a professional and, for example, tomorrow I will dedicate my day to DJing as July will be busy with shows.

But does the DJing inspire you at all for your studio work?

Yes it does, but I get more inspiration from the Berlin Philharmonic or from going to the theatre. I was brought up with classical music and this is still something that inspires me a lot. Inspiration is very important, as we all know. You can’t take inspiration from the inside forever.

Do you actively manage your inspiration?

I do try! In the past I used to work all night, but now I love to go early in the morning. Sometimes even at 6 or 7AM, because there is something peaceful in those moments. I also really like to do arrangements in the morning!

I’ve found that I am always more inspired when there is someone around. I spoke to David August and he said his inspiration is to be alone; Paul Kalkbrenner said his inspiration is silence, and being all by himself. That’s not for me. For me, it’s the opposite: I like to be with people in the studio. I have a really good thing going with my young studio partner. We play together, let the machines run. Play play play play! Making a performance again with the machines. I totally forgot how important it is to jam, to record from a feeling that you create—like a true live act!

I can hear this when listening to the new ToCo EP. It feels like you’re listening to two very skilled musicians doing a very controlled, but also intuitive live jam. Is that correct?

Yes, that is correct. Marco loves these two synthesizers, the Prophet 5 and the Jupiter 8. He plays them in a way that I never played them. He really listens to the sound and makes small changes; maybe he doesn’t always exactly know which knobs he is tweaking, but he has a great feeling for it.

I am totally obsessed with making sounds with the modular that are in a pitched tone, which are quantized. The modules have a 1V per octave input; with 1V per octave, you can guarantee a relation to the key note of your track. In the ToCo times, when we recorded our tracks, we always made sure all the sounds were in tune with the keynote. I really tried to use the Modular in the most musical way possible.

Then we also used other machines: for example, the 909, which you can use as a trigger for the modular. You can use the amazing and unique, unprecedented groove of the 909 and 808 to trigger anything within the modular. You can make the modular swing like a 909. This is a technique that we used a lot for the ToCo project.

So within ToCo, the modular is your spot?

Yes, that and some other synthesisers.

When did you start building and using your modular system?

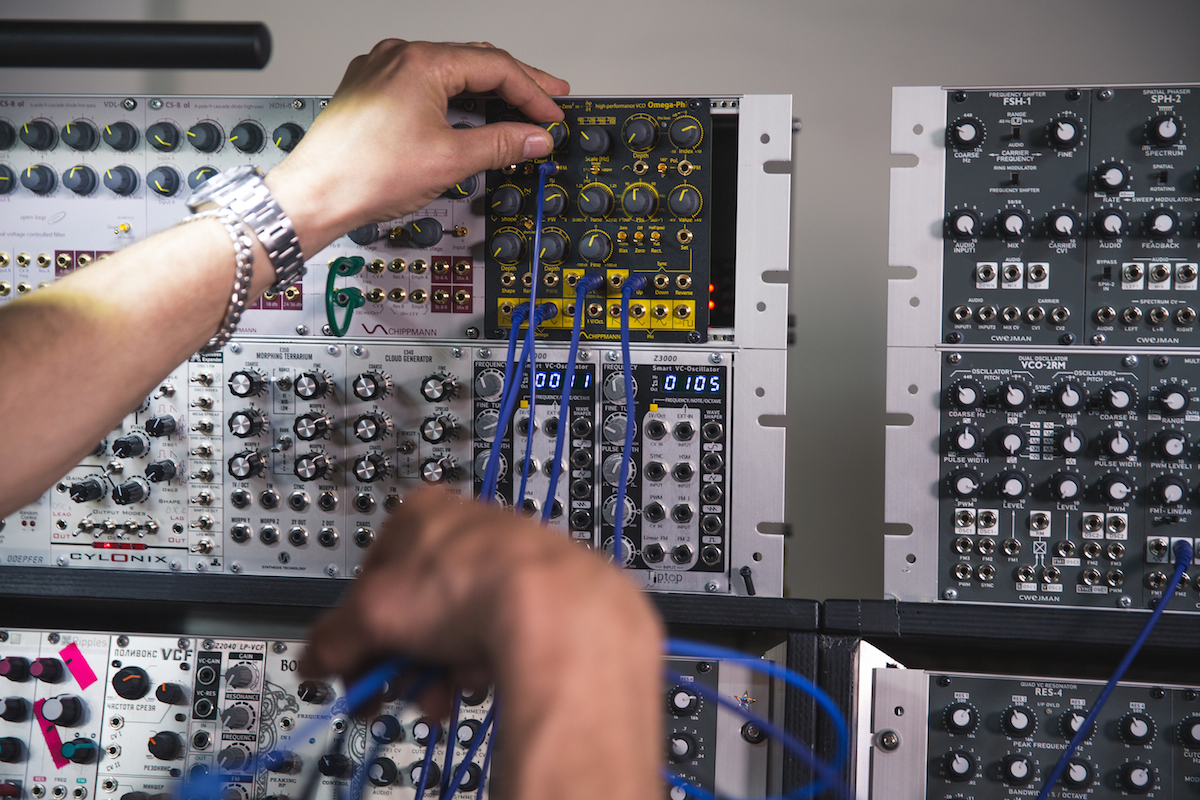

It began sometime in 2008 with a little starter kit from Schneiders Büro, and it grew over the years to a complex system with a lot of special and rare modules. It is quite an organic system with a fluctuation of modules. Now, eight years after I started collecting it, I would probably call it an almost perfect system. It’s maybe a bit large, but it has become an addiction—a lovely and not an unhealthy one! I used it from the beginning, but it’s now become a true instrument to me. I know exactly which sounds I can create with it.

Why did you decide to use it?

Onur Özer and myself visited Ricardo Villalobos in his studio. He showed us some sounds and grooves he made with his modular, and that’s where the infection happened!

What advantages does it offer?

Infinite sound possibilities, no presets, and also new ways to touch sound. There’s also absolute direct access to the electricity, instead of a digital algorithm that tries to imitate analog behaviour. Also, you’re not watching on a screen; you’re just listening to the actual sound!

How did you learn to use it?

Studying, studying, and more studying. Trying out, trying out, and more trying out. Reading manuals, books and watching helpful tutorials via Youtube and Vimeo.

What were your first modules?

A Cwejman MFF 1, which I still have, as well as the Cwejman frequency shifter. I also had a Livewire oscillator and two Livewire LFOs.

So are you sitting here for hours, just making recordings?

Yes, you always have to be ready to record. First of all, you shouldn’t forget to actually make tracks; if you don’t do this, you betray yourself. For ToCo we have much more material than we eventually used. So, it’s also good to put a blanket over the modular when you have recorded enough material, just so it doesn’t distract you! We usually do a recording session for a few hours and then focus on the arrangement.

“In the past I went back to old projects to use recordings for newer projects, but I don’t do that anymore. It takes too much time. I prefer to just make something new. Now I prefer to put the machines on and record something, quickly put an arrangement together and then let it rest for a little while.”

Does the session start with an initial idea?

It depends whether it is an original track or a remix, but it’s always good to start with a small idea. With ToCo, for example, we have a very free way of working. As a result of that, we made a lot of material which we later realized we wouldn’t use it, because it was not the direction that we wanted to go in. We just recorded five or six tracks in one day, and then later decided which ones to to continue with. It’s always good to let it sit for a while before going back to it later and thinking, “Ah, that’s cool, we should finish that!”

So you have a database with unfinished projects that you sometimes dive into?

Yeah, tons of stuff.

Do you go back to it a lot?

In the past I went back to old projects to use recordings for newer projects, but I don’t do that anymore. It takes too much time. I prefer to just make something new. Now I prefer to put the machines on and record something, quickly put an arrangement together and then let it rest for a little while. Then you go back to it a bit later to see if its worth finishing. To be honest, I’m not the master of finishing stuff!

An important tip I got from Ricardo Villalobos and Onur Özer is to always record what you did before you go home in the evening. It also gives you satisfaction in the morning, when you are in the bathtub, to hear what you did the day before. Lately I have been following this advice more and more.

Is it hard for you to go back to a project to finish it, because the initial inspiration is gone?

Yes, that is certainly a problem. I often just give the work to someone else, to restart it. Lately we have been doing it more and more at the Riverside Studios. It’s always good to give it to someone with a clear mind; someone who is not too touched by it personally. They are usually better at looking at the bigger picture—picking out which things work and which don’t, things that are very hard to see when it comes to your own music.

Distance and a good night of sleep help a lot also. Playing your track in the middle of a DJ set can often very helpful too, to see if the track works or not. Sometimes you think it will work like crazy and the people don’t like it. Sometimes you think it’s not that good, and people go mad for the groove for example. The second proof is always the people on the dancefloor.

Do you have a feedback group that you can send you material to, and does this feedback help you to finish tracks?

I have a few. I find it helpful to show it to girls, or to people that love music but who are not producers or musicians. They often give you honest and dry comments, things you wouldn’t think about when you are working on it in the studio, but they are right. It’s a very honest way of evaluating the music.

At some point it’s good to share your music with somebody, although not too much because it can also cause total confusion. It’s up to you to decide at which point you would like to hear someone’s opinion. You are in charge, so you make the final decision, even if it goes against somebody else’s opinion.

It’s a delicate matter.

Yes. I think it is good to open yourself to people, but I also see these producer bands, where there are 20 guys from record companies that all try to implement their individual opinion. This can do a lot damage to the music. That’s why we love the underground—you can make your own interpretation of your ideas without to much interference. In the end the truth is always the reaction of the people on the dancefloor; it is the purest, most direct feedback you can get for music.

You are working on different projects under different names. Are there specific combinations of equipment you use for these projects?

Yes, it is good to limit yourself. I think it’s good to, for example, choose a limited number of machines to work with for one EP. For the next ToCo recording session in July we will choose, let’s say three synthesizers, two rhythm machines, one modular, and one acoustically recorded instrument or voice. These limitations help to get a coherent sound for the EP. If you don’t limit yourself then the opportunities are endless. Not everyone is brilliant enough to combine all the elements in the right way.

Do you have a standard routing for your effects?

The effect routing on the mixer is stable. This helps me to quickly get the sound I want, which is great for jam sessions. On Send 1 I have a reverb; on Send 2 I have a room; on Send 3 I have an eventide; on Send 4 I have another eventide; and on Send 5 and 6 I have delays. Also there are just a couple of programs that I use to get exactly the sound that I need. When you have such a big studio, you need some standard routings, otherwise you go crazy, or you lose to much time with just making setups.

Is it important for you to have equipment coming into the studio? Does this help you to get inspired?

I don’t buy that much outboard gear anymore; instead, I mostly expand my modular system. Sometimes, with new gear, you just think it gives you new inspiration, but you are actually just too lazy to work hard. It’s not necessary to constantly buy new gear. It may actually be better to take one piece that you have had for ages in the studio, and just really dive into it. Some of the greatest music is made with nothing. Todd Terry, for example, I don’t think he used more than an MPC and a 909, maybe a Juno. These American guys all made brilliant music with a small setup.

What piece of gear would you recommend buying anyone that is looking to build a small but versatile studio setup?

The Akai MPC, because first and foremost it has groove, which computers don’t have. It also has the 16-bit sampling capabilities, which simply sound amazing. The workflow of the MPC is completely different from the workflow of a DAW. You take 30 records off your shelf, you sample them into your MPC and you make your own sound bank. You have to find the start and the end of the sample by hand, truncate it, and hand-craft your sample pack until you have 16 sounds on your pads—then, you can start to make a groove with it. The process is really important. It’s about not looking at the groove or its visual representation as you would on the computer, but rather hearing how it sounds. You are more focused on the ear.

Let’s discuss the studio. We are in kind of a special location here and it seems like you found your spot. Is there anything in particular that you look for in a studio?

Good air, a good vibe, good cosmic energy. Also, no problems with the neighbors, AC-control and good company! I like to have people around me, working with me in the studio or in their own rooms doing their music. Here in the Riverside Studio we have 20 different studios. Everyone is doing their own stuff, some commercial music, some underground, some rock. It’s nice to walk around and hear a guitar or a voice, and to see the different artists developing. I like that here. It’s a very inspiring and creative atmosphere.

It seems that you have transformed this basement space into a studio yourself. Can you tell us a little bit about this process?

I spoke about the concept with a specialist who was in charge of the acoustics. We wanted to achieve an open acoustic concept with a lot of diffusion and not that much absorption (you need both). I knew I definitely wanted a real wooden floor, which is very common in professional studios and clubs worldwide, because it helps to get the sound right. I wanted high ceilings and a big space which would enable me to go behind the racks, so I wouldn’t have to spend too much time crawling around on the floor looking for cables. This room met all the requirements. The studio itself was already there, so we just had to focus on the room, on the construction, on the materials we choose.

With such a big studio, with complex routings, it’s important that all the MIDI, audio and digital devices are connected and functional, especially when you work with analog gear. If something bothers you, fix it right away! And start every morning with a very slow filter sweep. This is rule number one in my studio: we start the day with a nice filter sweep!

Is it important to you to have a separate studio space and living space?

Yes, it is. I enjoy having a separate working space for studio work. I do all my DJ preparation at home. If I also had my studio at home, then I wouldn’t leave my house. Then there is also the social aspect: partnership and meeting other people is extremely important to me, because gives me inspiration. And I like to take the ride to Kreuzberg for work and to come home to the more quiet Prenzlauer Berg. They are two totally different parts of the city, even though they are not too far apart.

And you don’t continue at home on your laptop?

I would love to be able to do this, but I can’t. Maybe only for some small edits even. I remember that Recondite told me that he has his laptop always with him, which means that he can travel with his studio. I am a bit jealous that he doesn‘t need anything more than the laptop. I need my machines and my gear.

We looked at the past and the present. Now let’s take a look at the future. Is there still something you would want to achieve?

I would like to have a restaurant and make food for people. Besides that, I would like to share my knowledge with other people and not be on the road every weekend. I would like to help people to create sounds, and teach them to make a rich and lively sound arrangement—especially using the modular synthesizer, because I am really digging deep into the science behind the modular. People have noticed this and have started to ask us for help. I have been working with the modular for 10 years now, so I do have some knowledge to share with the new generation.

______

Tobi Neumann plays Movement, Croatia Jul 28 – Aug 1. Tickets here.