Studio Essentials: Alessandro Cortini

The secrets behind the Italian's new album.

Studio Essentials: Alessandro Cortini

The secrets behind the Italian's new album.

Alessandro Cortini’s new album is coming later this month, his first on Mute. The Italian artist, best known for being the keyboard player in the American band Nine Inch Nails, recorded much of it in Los Angeles, starting just after the release of 2017’s Avanti, his most recent studio outing, and finishing in Berlin, Germany, in April this year. Excluding the Lynx Aurora, a set of 16 audio converters purchased specifically for the album, he created it using the same setup as much of his earlier work, comprised only of gear that he’s carefully researched and sourced because it fits his individual ways of working. “Certain instruments have taken me years to find,” he explains. “I try not to obsess too much. I have ruined friendships over it at times, but it really depends.” One particular instrument, the Buchla Music Easel, took him nearly a decade to locate, “then when I found it I cried about it,” he adds. He proceeded to write the entire Forse series with it.

Cortini opts for older machines over newer variations, “because they’re designed to be the best they can be at the time but they’re also aged, so there’s an extra factor of variability that might not be present in modern analog just because analog is now based on more stable components,” he explains. “If I sit in front of an old machine and I feel that it has something to say, it just speaks to me more than newer machines.”

And this search for variability, this craving for the unexpected, is rooted in a need to continue his exploration of new patterns and sounds: it’s all about finding a balance between having the tools that he wants and the tools that dictate what’s going to happen. “I need to be inspired and to revert to being a child, to have fun without thinking about what I am doing,” he continues. “That comes down to how the synth sounds, but also how it looks, how the knobs feel; there are many instruments that I’ve thought sounded fabulous, but that I never clicked with. Some things speak to me; some things speak to me forever, and some other things speak to me in specific periods, and I won’t go back to them.”

Marking the release of his new album, out September 27, Cortini chatted with XLR8R about the key gear behind his work, elaborating on what he seeks out in his gear and how this manifested itself in Volume Massimo.

Alessandro Cortini will play alongside Avalon Emerson, Kode9, Rian Treanor, and many more at SEMIBREVE, a beautifully located festival in Braga, Portugal, on October 25-27, with more information here.

Mezzabarba MZero guitar head

Volume Massimo has quite a bit of guitar, and it was all recorded through this amplifier. I started as a guitar player, so guitar has always been there in a way, and I’ve always been seeking ways to blend it with electronic music. I think this particular record had more of an opening to reinterpret some of the synth lines with guitar. Originally, I thought I would use guitar across the whole record, but I usually go from one extreme to another and the truth is somewhere in the middle. Once I tried to impose it on every track, I realised that it works better in certain circumstances, and at times the music is better just with synths on their own. You can hear it on “Let Go,” “Batticuore,” “Momenti,” and also “Amore Amaro,” which is actually where I first recognised that using the Mezza with the guitar worked well with the synthy parts I had recorded.

Mezzabarba is a company I worked with on the last Nine Inch Nails tour. They designed the pre-amp for me to use live, and this specific amplifier, the MZero, is versatile and allowed me to use effects and pedals, and to recreate the sound that I grew up with; like more of a hard-rock, distorted sound. I purchased it while I was living in Los Angeles. I’m also proud because Mezzabarba is an Italian company.

I’ve used software for guitar for a long time, and it offers so many options, but at the end of the day I gravitate towards one main sound, so I thought: ‘Why do I have all these plug-ins when I really use only one sound from each plug-in?’ So I decided instead to have one good piece of gear and learn it as much as I can; to have one meat and potatoes sound, and then add effects to it. That’s basically how I used the amplifier. It wasn’t mic’d; I used a piece of gear called Torpedo by a French company called Two Notes. It basically emulates the speakers, and allows me to connect the head straight to it, and then record it without angering my neighbours!.

The physical aspect of being able to play by hand leads to me being happier with the sound instead of me having to continually tweak it; if it’s wrong then I’ll just re-record it instead of always keeping it “open.” The whole record is just recorded takes. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with using software, but I feel that if I commit to a take with everything printed then it allows me to achieve two things: to commit and move onto what’s next; and to allow for a more creative mixing process, where I can approach mixing just like the writing itself; where I can shape things in a certain way if they need a change. They might sound good if you have only two tracks going and then you mix the section that has 16, and then you go, ‘Oh wait, it’s kind of fighting.’ It really makes me feel more of a progression during the writing and recording process.

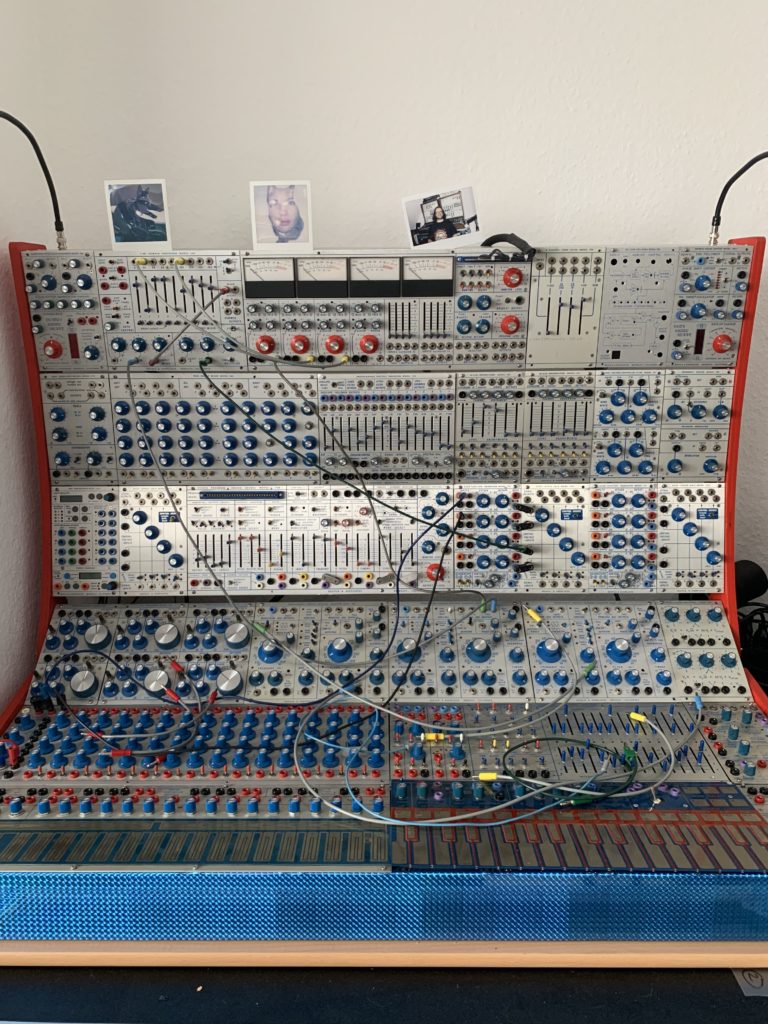

Vintage Buchla 200 system

This is a vintage Buchla, so it’s from the ‘70s. It’s been expanded over the years as I’ve found more modules, so now I have everything in front of me in an order and structure that makes sense. I use it every day, and it’s tailored to my own way of working. It’s my pride and joy, for sure, and, one way or another, I always go back to it to see what comes out, which is always interesting. I actually hardly ever approach a machine, especially not this one, for any specific reason; I normally sit on the machines, something comes out, like a texture or a melody, and I’ll then incorporate that in my music.

A lot of Volume Massimo was written and/or sketched on my Buchla. It’s an instrument that lends itself to creating a whole piece of music, and it feels so organic. It’s really a creature on its own as opposed to just a part. There’s one song, “La Storia,” which is exclusively Buchla 200; the main melody, which is played live on the Buchla 221 touchplate, is going through a delay which is modulated by a random voltage that jumps between two values. These two values make the delay jump an octave up and then down again randomly, and then I overdubbed another part on top of it. I’ve used it also for parts in certain pieces, like in “Let Go.” It’s a familiar playground, so it’s easy for me to sit in front of it and come up with something that fits, without thinking too much about it. It always gives me an answer of what’s missing.

EMS Synthi AKS MKII, modded

The entire Avanti album was written and performed on this one. It’s super alive and organic, and wonderfully imperfect, which leads to a lot of unexpected variations. Experience has taught me to accept things like that. I want to find a balance between having the tools that I want and having the tools that dictate what’s going to happen. I feel the Synthi is a good balance between the two.

I used the Synthi across Volume Massimo too. The record started with “Amore Amaro,” which was kind of written around the time of Avanti, so this was born completely as a Synthi piece. There was a time when I was deciding what to do after Avanti, and “Amore Amaro” was always with me because it’s such an interesting sequence, and that sequence is due to the irregularity of the KS of AKS, which is the keyboard sequencer.

It’s a rudimentary sequencer in the sense that if you’re trying to programme something you have in your mind then it’s going to be very hard to replicate it the way that you want it to. The cool thing is that if you input something then you might get a version of it that you didn’t think of, and that allows for these happy accidents.

When I started working on this record, which I didn’t actually know was going to be a record at the time, I decided that I wanted to try to expand my vocabulary, so I started by just overdubbing Synthi on Synthi. I’ve always had a fear of using the studio as an instrument, like using every piece of gear on every piece of music; it’s like using all the spices in a kitchen when you’re cooking dinner: you come up with something that is very flavourful but with no nutritional content. But the Synthi is such a strong character and so it’s pretty much all throughout the album.

“Amore Amaro” is essentially all Synthi: the main sequence, the bass, the high melody. I then overdubbed guitars. “Amaro Amore” is pretty much the same thing: born as a main sequence on the Synthi, transposed with the KS, then I added another Synthi melody on top. I also then overdubbed parts with an Ondomo synthesizer. “Momenti,” again, same thing. The main sequence and melody are done with the Synthi, and then there are overdubs with the Waldorf Quantum. The end of the track is a mangled guitar from an iPhone voice recorder idea. I used Logic’s Flex algorithm to make it sound wonky. I mean it was pretty wonky before but now it’s super wonky.

Buchla 700

This is an odd one, a digital Buchla from the ‘80s. I also have a Buchla 200, which I acquired in Mexico City in 2008, I think. The 700 I bought from a collector years ago as well. It’s a 1987 digital Buchla, so it’s much more complex to use. The machine tends to be a bit unreliable, so I’m trying to get as much stuff out of it as possible before it breaks down. I have a full spare unit just in case, but I want to avoid opening this up to look inside.

The 700 is more about shaping a simple sound in a complex way. I’ve used it a lot on several pieces, in particular the “Let Go” synth part. It’s just a very analog-sounding digital, in the sense that it’s very raw, and I love it. It is not the most immediate instrument to work with, but it is full of surprises and it’s fairly easy to extrapolate organic and interesting sounds. The fact that it has built in MIDI makes it easy to program and control from an external sequencer.

Lynx Studio Technologies Aurora (n) audio converter

Audio converters are things that you don’t really mention enough if you work with a computer. There are two reasons why I’m super happy about the Aurora: firstly, the quality of the converters. I really didn’t know how much of a difference they would make. Just as when I bought my first analog synthesizer as opposed to a plug-in, which was always great, it feels like the sound now has a defined space in the spectrum and it’s much easier for me to mix and to understand what the role of a specific instrument is going to be.

The other aspect is that it has a built-in recorder, so I can document anything I am doing in the studio at any moment, without turning on the computer. It essentially allows me to bypass the computer and use it as a high-quality multi-track recorder, and then I decide what to do later with those files.

All of my instruments are in the patch bay and default into the Lynx, meaning that I can be playing and recording on the Micro SD card without thinking what that stuff is going to be; so I can be purely creative, and then I can go back to it when I am travelling, and load those files into a Logic session or whatever, and figure out what I am going to do with them.

It’s a liberating thing because even though it might not be like this for everyone, for me to know that I’m fucking around in the studio and then I have to turn the computer on to know how ready it is holds me back because I’m already thinking about BPM and tempo. As long as the instruments are tuned between themselves, I don’t think about all of them being tuned to a tuner/standard tuning Hertz. As far as BPM, instead of finding a BPM in logic, I let the machines play at whichever BPM I feel comfortable with and deal with finding what BPM it is later, if at all.

It’s also a small company so if I have any issues then I can reach out and I’ll get a response quickly, unlike other companies I worked with where it might take longer to get an answer to an issue.

Waldorf Quantum

I bought the Waldorf at beginning of the album mixing session, which, for me, is a period that goes well beyond just mixing. This is the time where I make all the tracks fit together. It’s like a puzzle: I have all these pieces and I listen to them together and then make the final changes. The Waldorf provided the right ingredients for me; it was like the clear coat that glued the music together.

The machine came via a recommendation from my friend Richard Devine, who had worked with them originally, and also Richard James who loves the instrument too. When those two Richards speak, you have to listen. It really is what they described. Out of all the instruments from the last decade, it’s the one that sounds like a universe on its own, and it finds the perfect point of having the right features and ease of use in accessing these features.

I was originally looking for a piece of gear that would provide something for granular synthesis, and to manipulate audio in a creative and immediate way. I wanted something outside a computer to do this: I’ve done it many times before with software, but I wanted something different and the Quantum seemed like the perfect answer.

It’s very easy just to keep it connected to a patch bay and feed it an output from Logic, and then sample it and mangle it into an instrument; it’s immediate in this way. That was the way I got into it, then I realised how unique an instrument it is.

Every sort of synthesis that it offers is presented in a meaningful and creative way. I can get lost in it very easily, but not in a way that four hours pass by and I haven’t come up with anything interesting. I started writing patches for it, and I keep overriding the ones that are in there, and then I started using it on the record for several things, like on “Let Go,” where the speech synthesis is actually from the Waldorf. You can input a phrase and then the synth will play it back, and then you can play it on the keyboard. It’s also used on “Momenti” for a harmonium sound, and a string counter-melody that sounds like violin, but it’s in reality a Buchla 700 that I adapted to a granular sound within the Waldorf. I am sure I used it in other parts too: as I said, it became like the spice for the album, used to give a common denominator to all tracks.

‘Volume Massimo’ LP is out on Mute on September 27. You can pre-order the album HERE.