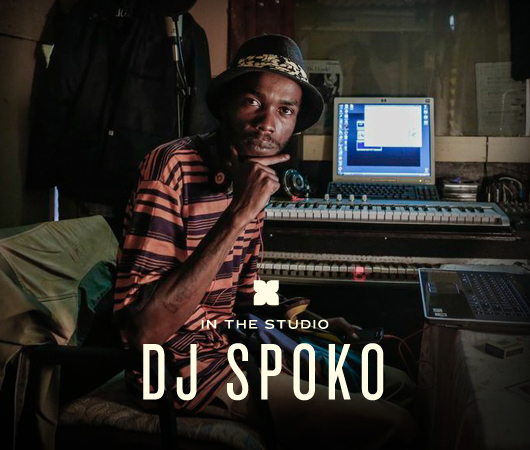

In the Studio: DJ Spoko

From his base in Atteridgeville, South Africa—an almost entirely black township located outside the mostly […]

From his base in Atteridgeville, South Africa—an almost entirely black township located outside the mostly white city of Pretoria—Marvin Ramalepe (a.k.a. DJ Spoko) has in the past few years created and proliferated his own brand of house music, which he’s termed “Bacardi house.” A style which became popular at the township’s nighttime outdoor parties, usually attended by many “Bakakathi” (the local slang for “gangster”) with a taste for Bacardi cider—hence the name—the stripped-down productions favored raw rhythms and sharp percussion instead of the smooth and deep house crafted by many of Ramalepe’s peers. While his recent Ghost Town EP for True Panther may serve as a first introduction to many outside South Africa, Spoko is certainly not a new artist by any means; he started making tracks in the late ’90s and later studied production and engineering with Nozinja, the creator of the Shangaan Electro style. Along the way, he also became one of Atteridgeville’s premier producers and jocks. With all this in mind, we were curious to find out just how and where Spoko crafts his unique brand of house, so we paid a visit to the man’s studio, which happens to be situated in a small tin shack behind his house.

XLR8R: When did you start producing?

DJ Spoko: I started around 1997, just programming with a computer running Evolution Studio LE.

And what style of music were you making then?

I started out making the same stuff that I do right now, Bacardi house.

Did you come to the world of production from DJing?

No, I DJ now, but back in those days, I didn’t. I was trying to be a sound engineer. I had gone to Soweto to learn to produce and do some engineering, [but] I started DJing when I moved to the township.

Do you think having that experience as a DJ now helps you when making tracks?

Yeah, it helps because I always know what the people want. [When you DJ,] you are there with them and you can find out what kind of a beat they are looking for.

How do you usually start a track? With a sample, a drum loop, or something like that?

No, I don’t just start a track—it has to be in the head first, you know? Once it’s banging in my head, I start to make it happen with the keyboards. I can hear the full track in my head, and then I have to separate it out—figure out what the key is, find how the bass goes. Sometimes I’ll have to leave the idea behind because I end up with something better.

And you can recall the ideas in your head with enough detail to get them down?

Usually, yeah. I always carry my laptop, it’s like a mobile mini-studio, so when I hear an idea, I can just lay it down on there before I get into the studio to do the final thing.

Are there ever times when you don’t have an idea in your head and are just messing around to see what happens?

Yeah, if there’s nothing in my mind, I just play around. Actually, that is when I come up with the stuff that I love the most because I had never heard it before. [laughs] Like the song “I Remember,” I was just messing with the vocal of my friend G-Dog, he had recorded an intro for a hip-hop track I was doing, and I just started messing around with that and eventually came up with a new track.

How do you get your sounds? Do you do a lot of sampling or are you recording musicians?

Some instruments I play live, some are samples. Sometimes, I’ll sample a single sound into the keyboard and then play it on there.

And then you arrange the tracks using your computer?

Yes, when I’m sequencing the music I use Fruity Loops as the main program, but I use Cubase to record and edit vocals.

What’s the workflow like when you work with vocalists?

Many times, I’ll have a vocal line in my head, maybe without any music—just a vocal banging in my head. Then I’ll try to translate that idea onto a track with the help of the artist. Other times, if they have a specific style or gimmick, we just go with it. On the track “Azange,” I had thought of everything in my head and then I had Magaula and Puzuzu come into my studio and sing it all for me.

Do a lot of your peers’ studios look like this or is yours unique?

Mine is one of the smallest ones around. I actually like the size because I don’t have to plug in too many things and I know it really, really well. In big-time studios, there is just so much stuff there and you work hard to use it all and to try to convince yourself that everything is sounding okay. If I could, I’d just use a laptop and no mixer, but that’s not possible right now.

What do use the mixer for?

Everything comes through the mixer—my keyboards, the computer running Fruity Loops—and then into my laptop [where it all gets recorded]. From there, I’ll start editing and go play out what I’ve recorded. If everything is not right, I’ll come back and edit again and again until it’s good.

So how long then does it take you to finish a track?

It’s amazing because it usually only takes me 10 to 20 minutes.

And that includes the mix?

When I program, I mix at the same time. When I am putting the snare and kick in the right positions, I’m adjusting the levels at the same time.

You must have a lot of tracks lying around then?

Yeah, I have a lot. [laughs] Ain’t nothing else I can do but make music everyday.

Would you say you have a signature sound or some element that ties together all the music you make?

My synthesized strings—you can’t miss them in my music—and my sub snare. That snare is a sample that I made—it’s actually a combination of snares. I tried to combine them all so that they had this really deep sound, so you can feel it. I use that snare in all of my songs. Even the young producers who come up through me, they know that without that snare, you ain’t going to be next to Spoko. You have to have it. That’s why you’ll hear it in so much Bacardi house, because I distributed that snare sound to the young guys who wanted to make that style [of music].

Do you help a lot of younger producers get their start?

Yeah, I do a lot of mentoring, a lot of teaching. I’ve got a solid line of DJs that have come through me. I’m just trying to build my township. DJ Mujava was one of my students—still is one of my students. Those I believe can make it, I try to help out. Guys like Mujava, who used to come to my crib everyday in the morning and wake me up. That shows that they have potential and are serious about what they’re doing.

And you’ve done that for years now?

Yeah, that’s why they call me the Emperor Spoko—I’m the first one to do this, the number one, you know? [laughs]

All right, last question. Say you had all the money in the world to build a studio, what’s the one thing you would absolutely need to have?

If I had a bunch of money, I’d make sure my studio was completely digitally equipped—to get that real clean sound. If I had that, I’d just lock myself in there and throw away the key.