Review: Semibreve Festival 2019

Adventures in sound and vision in Portugal.

The 40-minute ride from Porto airport to the city of Braga is dramatic, moving through steep, wooded hills which, in previous years, have been torched by brutal forest fires. But 2019 has been kind, our driver told me, and the arid roads are lined once more with weathered trees, unscathed. Braga itself is no less impressive, a crucible of Mediterranean history that’s all tight cobbled alleys, medieval courtyards, and so many churches that you’re never more than a stone’s-throw away from salvation.

Braga is also the home of Semibreve Festival, a thoroughly present-day programme of modern electronics and club sounds from the fringe which runs from Friday to Sunday evening. This is edition number nine, with previous years, also attended by XLR8R, featuring heavyweights like GAS and Roedelius. A return visit in 2019 was made compelling by two things in particular. First was the appearance of both Morton Subotnik and Suzanne Ciani on the concert programme, two early pioneers of electronic music and modular synthesis. Their enduring influence is clear from the amount of Euroracks that were on show over the weekend. Second was the club-night lineup, which was certainly the strongest ever hosted by the festival, featuring Avalon Emerson, Kode9, Rian Trainor, and Nik Void.

Semibreve is a strange proposition on paper: with a population of no more than 200,000, Braga doesn’t have an obvious audience for underground music. Yet for all three nights, the magnificent Theatro Circo—a large, gilded, red-clothed hall which hosts all of the main evening concerts—was nearly at capacity, and the festival’s two late club-nights (Friday and Saturday) at the nearby gnration arts centre were similarly packed. The night I arrived, a separate but equally adventurous festival, Index, a five-day media arts event, was also just wrapping up.

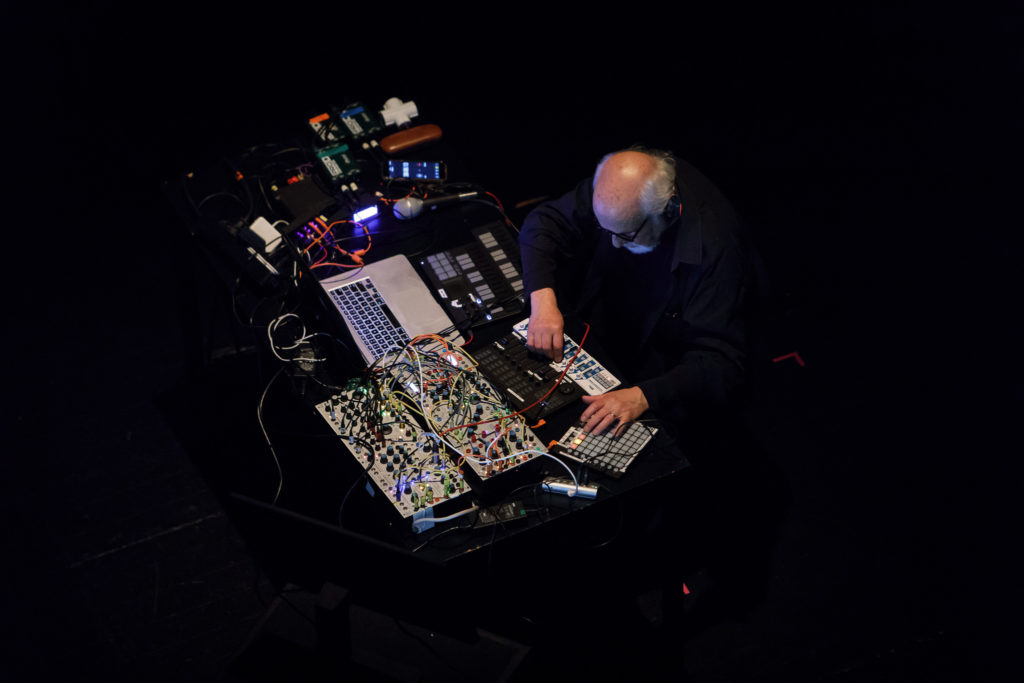

First to perform on Friday evening was Subotnik. Still touring at the age of 86 with an enthusiasm that belies his years, his appearance on stage at Theatro Circo was met with great fanfare. He is a wryly appropriate opener for an electronic music festival: his Silver Apples of the Moon LP, released 1967, is often credited as the first electronic composition released on record, and the modular synth he had commissioned to make it, the Buchla 100, was one of the first commercially available models. It’s an instrument he claims he’s still learning to use.

Subotnik began by flooding the hall with quadrophonic, waterlogged drones which hovered around no note in particular. These were decorated with scraps and bursts of sculpted noise, at times imitating sounds found in nature, like the fluttering of pigeons in a loft, or the sea crashing into the rocks. Gradually it built into gorgeous passages that weren’t far removed from the melodic, kick-drum-free type techno popularised in recent years by Barker and others.

Accompanying Subotnik on stage was Berlin-based video artist Lillevan, which left me with some questions that followed me for the entire weekend: it seems de rigueur for electronic musicians and DJs to compliment their live shows with visuals, but what exactly do these visuals say which the music can’t? And what distinguishes a meaningful visual element from a glorified screensaver?

It wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to say that AV shows were the unofficial theme for the weekend; the organisers told me that this was something they wanted to pay particular attention to and the topic came up a lot in the two talks they did. It was also something most of the audience seemed to notice (e.g the different types, and how Ambarchi and Robert Lowe didn’t use one at all, more on this to come later).

On the subject, however, Semibreve provided more questions than answers. Over the weekend, there were three performances that highlighted the diversity of approaches to AV shows today. The first came from Alessandro Cortini, best known for his synth-work in Nine Inch Nails, but receiving praise in recent years for his solo work. He followed Subotnik at Theatro Circo.

Cortini’s latest release, Volume Massimo, which runs in the same vein as 2017’s Avanti, is a set of slow-burning compositions built from layers of over-saturated, high-emotion synth that sound like they’re being burnt straight to tape. Cortini’s set sounded like a straight play-through of the record, but each song was accompanied by its own short film. Most featured mesmerising choreography, performed across scenes such as a decaying stately house and a warm, pastel-coloured villa. They were utterly arresting, and their combination with the music went straight to my head.

Cortini’s show was akin to a screening, a deliberate pairing of sound and vision to create a singular experience. Contrast this with Sunday evening’s set from UK producer and Warp affiliate Scanner, who performed on a modular system lent to him by a Lisbon-based manufacturer. As he explained in a talk on the Friday night, he arrived in Braga some days before with no idea how the system worked: the modules are pre-release, with no instructions available. During the talk, he revealed he is generally averse to playing alongside images or video. We are more visually literate than we are with sound, he suggested, and images have a habit of dictating the narrative.

That said, on the Sunday, he was joined in Theatro Circo by Portuguese filmmaker Miguel C. Tavares. At the Friday talk, Tavares was similarly unsure what might happen, yet what the pair created was extraordinary. On stage, Scanner visibly wrestled with his machines, eking out sound, perfecting grooves on the fly, and slowly sinking into something lush and dubby. Tavares’s visuals responded in kind, a palette of shapes and textures on which activity peaked and troughed in time with the beat. They were abstract by necessity, an attempt to respond to one of a million performances that Scanner might have produced on his mystery synth. It amplified the possibility of other realities, like if had Scanner been in a different mood, or had played on a different day.

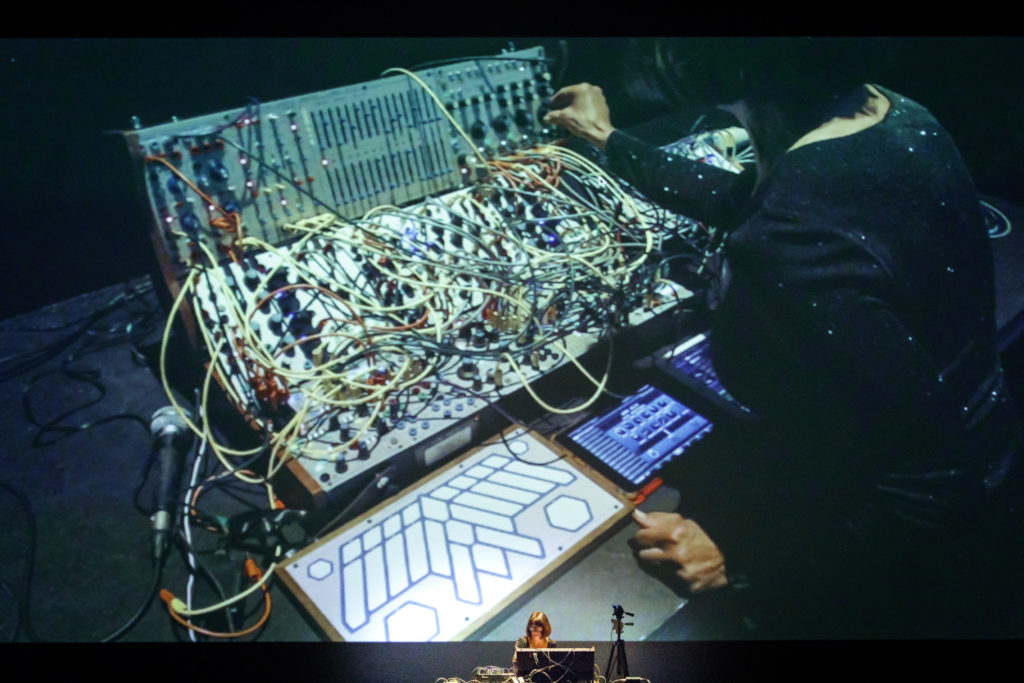

The third AV perspective came from Suzanne Ciani’s weekend finale. Like Subotnik, Ciani is esteemed for her pioneering work on the Buchla. For her visuals, a live feed of her workspace onstage at Theatro Circo exposed an intimidating array of synth modules, sequencers, controllers, and so many patch cables that she often had to fish her hands through the knots to reach dials and buttons.

In this case, the projection opened up the process of the music itself, a refreshing experience when so much is made of what and what doesn’t constitute a “live” show in electronic music. Yet for all the transparency, Ciani’s set retained a sense of the magical: a spellbinding 40 minutes of cascading arpeggios and retro-futurist wonder. It’s always something to watch a master at work, and these prying visuals made things feel very up close.

Others that must be mentioned include guitarist Oren Ambarchi’s improvised collaboration with underground mainstay Robert AA Lowe, and a performance of Coil’s 1998 drone-work Time Machines from Scottish-born artists Drew McDowall and Florence To.

The former dispensed with visuals altogether. Speaking at dinner two nights before, Ambarchi said he’s far more interested in immersing people in sound, and on Saturday evening the pair achieved exactly this, delivering the weekend’s most still and delicate set. Theatro Circo, plunged into near darkness, was filled with prolonged silences and faint whispers of sound. These gave way to slightly livelier sections of gentle vocal work and swells of alien guitar, which made for an enjoyably disorientating listen.

In contrast, following Ambarchi and Lowe, Time Machines proved the festival’s most intense moment. Drew McDowall originally conceived the work in the ’90s before bringing it to full fruition with Coil, and the name is partly a reference to the power of ceremonial music such as religious chanting to displace a listener in time. McDowall is accompanied by Florence To, whose colourful, line-based visuals often seemed to resemble shape-shifting landscapes. Witnessed live, it was overpowering: a loud, superheated sequence of head-melting synth drones which clearly took some audience members to very different places. Afterwards, one was pleased to tell me that, as promised, linear time became all but irrelevant, and that they’d got their money’s worth.

One of the best things about Semibreve is the curation, which creates a polar opposite experience to that of the bigger experimental get togethers. Not one name on the lineup would have been out of place at Unsound, but whereas the Krakow megafest runs stacked bills across multi-room venues that last well into the following morning, Semibreve is always scheduled such that there’s virtually no crossover between artists. Like previous editions, the evening programme all takes place in the theatre, leaving gaps between shows which, frankly, is a very welcome change of pace. It gives attendees a chance to decompress between the often challenging sets.

Saturday and Sunday afternoon also featured short afternoon concerts at venues no more than 10 minutes on foot from the theatre. This gave attendees a chance to explore the city, an attraction in itself which can trace its roots to pre-Roman times.

At the Capela Imaculada do Seminário Menor, a beautiful and starkly minimal chapel which contrasts with the highly decorated churches that surround it, the Norway/Berlin-based duo Deaf Centre used a grand piano and fx-heavy guitar, sometimes bowed like a cello, to fill the hall with deep and mournful melancholy.

The next day at Salão Medieval da Reitoria, a restored Medieval hall used by the local university, Félicia Atkinson’s set was like a guided meditation, organ-driven with fractured vocals and scatterings of notes, samples and moods. These short matinees were in keeping with Semibreve’s relaxed air, leaving plenty of time for dinner and end-of-summer beers in the dusty streets before the evening’s main event. Any more would have been too much.

The Friday and Saturday programmes included club nights at the nearby gnration arts centre, a former police station and play on words: “GNR” is Guarda Nacional Republicana, the Portuguese cops. Friday saw Factory Floor’s Nik Void go solo, with a raw hardware techno workout that built with a similarly raucous energy to that heard on her recent and final work with Carter Tutti Void. Avalon Emerson followed, opening with what I could swear sounds like a cut-up edit of Gina G’s “Just A Little Bit.” I could definitely be wrong, but in any case it was one of several nods to high-drama trance and eurodance that followed. Naturally, this was a lot of fun. What’s best about Avalon is her off-kilter additions to the mix and fear-free blends: a wild and choppy salsa-style piano solo stands out in particular.

However, Saturday night was arguably the better of the two. Hyperdub bossman Kode9 was on rare form, banging out a typically eclectic mix of footwork and heavy-handed UK fare, before pivoting towards much welcomed nostalgia at the end of the night with Martyn’s remix of “Broken Heart,” a cherished tears-in-the-club classic.

But Rian Trainor was the standout. The Northern England producer belongs to that thrilling strain of producers looking to reinject the ecstatic into club music, with other examples including Errorsmith, Gabor Lazar, Lorraine James, and much of the Nyege Neyge roster. Urgent and complex rhythms, minimal synths and samples, and humour all play a role: halfway through his set came what’s unmistakably an edit of Yello’s “Oh Yeah” (yes, the Duffman theme), albeit heavily sliced and played at some 150bpm. It was a blistering, joyous encounter.

With its 2019 edition, Semibreve once more confirmed its status as one of the finest and most thoughtful of small European festivals, and an essential consideration for anyone who’s felt burnt out by the bigger underground events, so often defined today by their bewildering level of choice, or the long hours hanging around at the rave for your favourite to make an appearance. Whereas they have grown bigger, favouring enormity, Semibreve has kept things intimate, creating an ideal environment to reflect on performances and the festival’s general themes. This year’s questioning of live visuals and their function proved stimulating, and felt overdue at a time when the AV show seems increasingly ubiquitous. It will be interesting to see what subjects Semibreve touches on in future.

All photos: Adriano Ferreira Borges