The Factory: Lauren N. Bailey & Collin Fletcher

A peek behind the Los Angeles intermedia artists' work.

The Factory: Lauren N. Bailey & Collin Fletcher

A peek behind the Los Angeles intermedia artists' work.

Today is our latest edition of The Factory, a series that explores music’s relationship with other art forms and how it permeates into the aesthetic of the visual artists, designers, studios, and event producers that operate behind the scenes in the music industry. The last time The Factory appeared on XLR8R’s pages was in August, featuring visual artist João Salgueiro (a.k.a Tombo). After Lauren N. Bailey and Collin Fletcher recently featured as our visual artists on XLR8R+, we thought it was time to continue our exploration of the work of the talented artists behind some of our most loved labels, events, and music. You can find out more about XLR8R+, our movement to support independent music and journalism, and how you can help support independent culture HERE.

Collin Fletcher’s profile across music has been on a steep upward trajectory over recent years, fuelled by his textured record sleeves, cassette tapes, and band T-shirts. His work, influenced by punk and DIY aesthetics, is characterized by its moody and atmospheric aesthetic, created with a mix of black, burgundy, and navy with odd flashes of white and pink. “I think that when things are black and white you’re paying more attention to the form and the images rather than the colour making you feel some kind of way,” he says.

Originally from Tempe, Arizona, Fletcher began his career as a design student, and found his way into music by being a promoter. Work with labels Ascetic House and Halcyon Veil led to art and design commissions for other electronic artists and labels like Tri Angle, Ghostly, Kranky, and Warp, and inspired a move to the West Coast to focus on creative direction for Yves Tumor among other more mainstream acts such as Post Malone, Zedd, and Halsey. He’s primarily working on physical releases—LP/CD/tape—but he also focuses on live promotion and production, merchandise design, fashion, and occasionally video.

Bailey, by contrast, works primarily with posters and flyers and specifically on type and type layouts. She likes to incorporate different manual processes and apply real, physical qualities to her work, even when the work may only function digitally. These processes include screen printing, linoleum block printing, rubber stamps, manipulating fabric, as well as playing with printer halftones and paper textures.

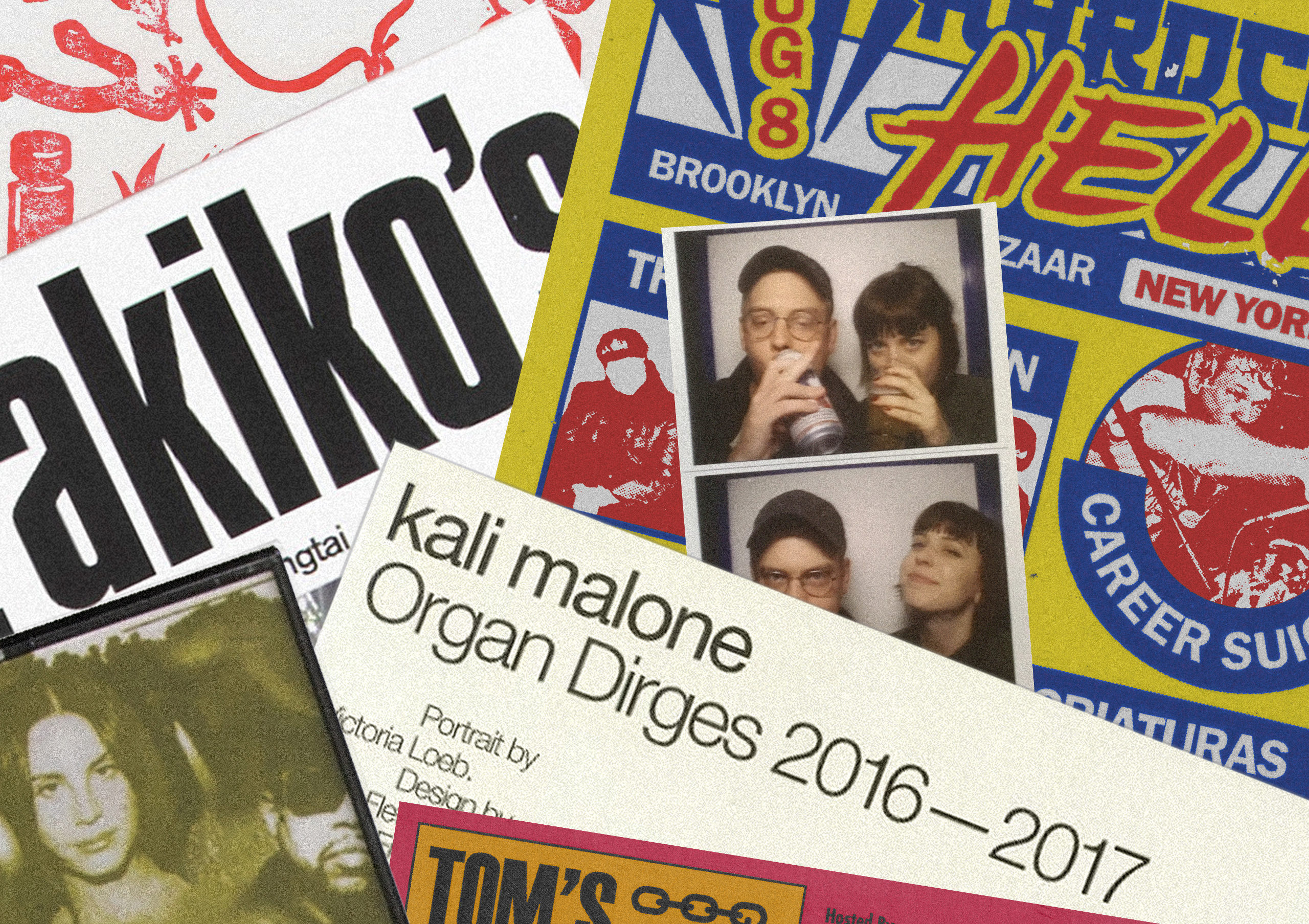

Nowadays, Bailey and Fletcher collaborate on projects, including HOCO Festival and our recent XLR8R+ design, a collage of their work that represents their physical, punk influences even though it was done completely digitally. “From a process standpoint, it represents exactly where we’re at right now in our own practices,” they explain. We caught up with them one day to learn more about their work.

How did you begin working together?

We were in the same class in the Arizona State University Graphic Design program, so it was most likely helping each other with projects. Having the same educational experience has definitely led us to seek each other’s input, even on our individual projects.

How does it work when it comes to a collaborative design?

It usually works like the exercise you’d do in elementary school writing class where one person writes a paragraph in a story, then passes it on to the next person to add their own paragraph until you have an end result neither person could have come up with on their own. It often starts with a photoshop file, saving it, and then passing it back to the other person. On other occasions, it’s simply asking for feedback while in the middle of working on something.

How do you feel the end result differs to your solo work?

Working together might be kind of comparable to having an editor as a writer. We let each other know what’s working and not cutting it in our designs; we offer each other new things to consider and tell each other what areas might need more work. Maybe the end result doesn’t differ from solo work but it’s supported and more considered.

“..I focus more on trying to find the best way to visually communicate the information. If someone decided not to read all the text on a flyer, hopefully the design would still communicate a general vibe or idea.”

— Lauren N. Bailey

How do you each map out and decide which processes—digital, physical, printing—to use?

CF: The production requirements are a big determining factor for which processes I use. For example, if a show poster needs to be implemented into a ton of different social media banner sizes and admats, etc., it’s much easier to use a digital texture and have the ability to work with an editable file that appears printed so I’m not reprinting and scanning constantly. However, working physically does look best, so album covers or graphics worth emphasizing the small details on will usually have some physical step, whether it be printing and scanning the whole graphic or tracing, handwriting, painting, etc. Nowadays, most of my work is a combination of both physical components and digital-specific methods, which I think is the most contemporary process. Computer software has incredibly powerful tools that didn’t even exist five years ago. I try to remind myself that staying current with technology is as important to timelessness in design.

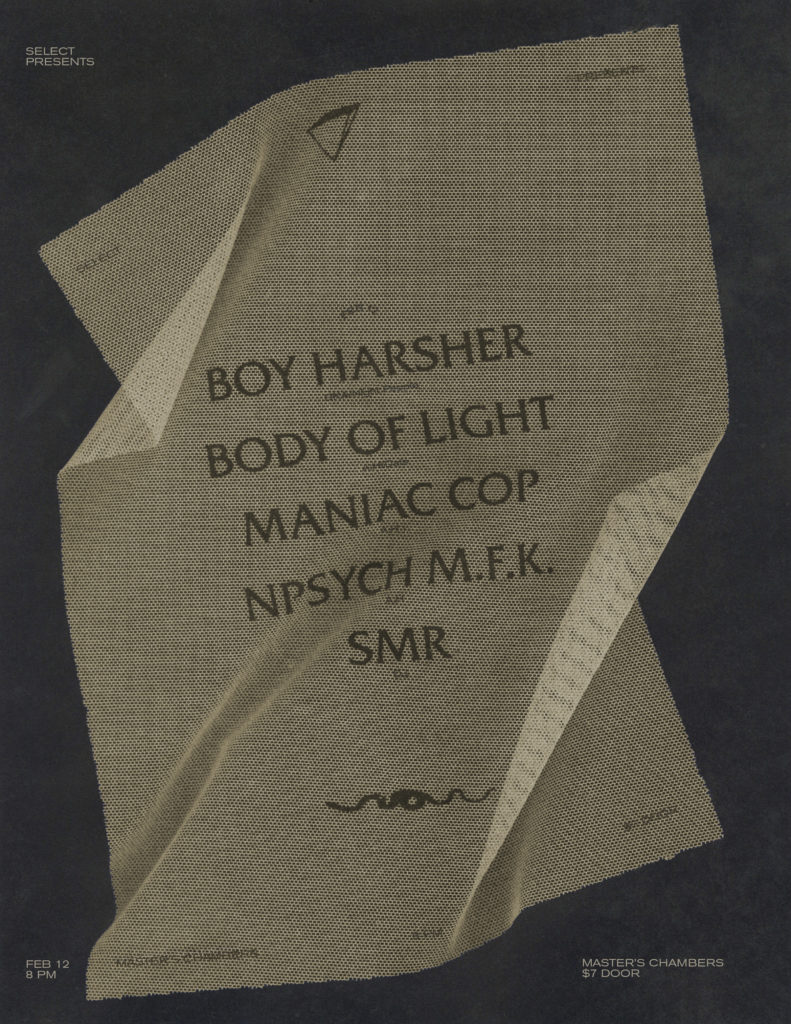

LB: I try to use whatever medium makes the most sense, but sometimes I decide solely based on what I am curious about or wanting to play with at that time. The flyer for the 2017 Boy Harsher show in Phoenix was screen-printed on a mesh-y beige fabric because I was influenced by photos I had seen of band-members Jae and Gus draped in a similar material. On the other hand, most of the linocut projects were done as linocuts because I was trying to teach myself to work in a different medium. Another determining factor would be time, of course; if a project has a tight deadline, hand carving a linoleum block might not be the most practical!

How do you find the balance between staying true to your style and continually innovating?

LB: I’m not too concerned with sticking to a specific style; I focus more on trying to find the best way to visually communicate the information. If someone decided not to read all the text on a flyer, hopefully the design would still communicate a general vibe or idea. I think that’s more important than making stylistic decisions that say “Lauren made this” or something. Even saying and practicing that, the “style” usually comes out organically.

CF: Yes, I think there’s a natural tendency to execute your own “style” regardless. It’s like the way you walk or how your voice sounds; what’s recognizable about you isn’t conscious to yourself. I’ve formed habits in my technique and established go-tos for typefaces, colors, and textures. I think the collaborative element of working with new clients while maintaining these habits and go-tos provides that balance between personal integrity and innovation.

It feels like you’ve both found your voice in a saturated world. What’s the secret?

LB: Stay curious about things outside of graphic design. I’m mostly inspired by everything outside of a more direct design culture. I think that is what keeps things fresh and interesting. Keep making, too; when there is a lull in client work, make personal projects. I also think it’s good to take breaks from client work. For me, personal projects help reconnect with the voice you are referring to.

CF: One hundred percent agree with Lauren. Don’t perceive yourself as a part of a scene or specific industry. If you’re a graphic designer, approach your practice like an artist or musician. If you’re an artist, approach it like a designer. Recognize your peers and learn from them; don’t think of others in your field as competition. Don’t “break into” a scene; do your own thing until like-minded people find you!

What’s the process when doing work for clients in music? Are you generally given briefs or guidelines to work to?

CF: In terms of working on a release, the artist usually comes to me with an idea or a general mood they’re hoping to convey and I’ll work with them through every revision until we’re at a result that we’re both happy with. The larger artists are actually much more unpredictable. Sometimes the major label’s direction and feedback is whom you’re answering to because it’s a marketing thing. Other times the artist will accept and love the first idea sent over because the graphic side is far less important than their appearance in a photoshoot, for instance.

LB: Every client is different. Some people have a specific idea in mind, and just need someone who knows how to make it happen. Other people may have ideas about their art direction but want a lot of the designer’s input and ideas. I’d say in all cases, I start with doing research. I’m a moodboarder and I am not ashamed to say I pull references before I get started. The design process usually involves initial directions that are slimmed down to a single direction. Following is a lot of back and forth, going through variations of that direction and small to large changes of the design until we can both settle on something we mutually like. I am usually in my computer in Illustrator before moving onto any other process like screenprinting and linoleum blocks.

“Yves Tumor calls all the shots but ultimately gives Creative Director Isamaya Ffrench and I the freedom to craft this character into our most fucked version of a pop star we can imagine.”

—Collin Fletcher

How do you find the balance between satisfying the client and your own creative instincts?

LB: It can definitely be difficult. I don’t really agree with the customer is always right mindset. If you are hired for your expertise, then your opinion and decisions should be understood. Client feedback is very important though! Sometimes you have been staring at a design for 10 hours, and you send it off not knowing what it is missing. A client sees it with fresh eyes and knows exactly the thing to do to make it better. Client work can be collaborative and often the results are significantly improved with the extra eyes.

CF: I haven’t found that balance and probably never will. Every client is different and on most occasions it’s more than one person’s opinion that you’re catering to. I try to accompany every draft or idea with written reasoning, especially if there’s an obvious, generic alternative that you anticipate the client is looking for. Addressing that before they have a chance to respond with “what if you tried this…” reinforces your decisions. Also, it’s important to pick your battles. Evaluating which decisions are more important than others prevents a dynamic where you’re butting heads with the client every step of the way.

Collin, can you talk about your work and art direction for Yves Tumor—how did that come about, and how does the working relationship work?

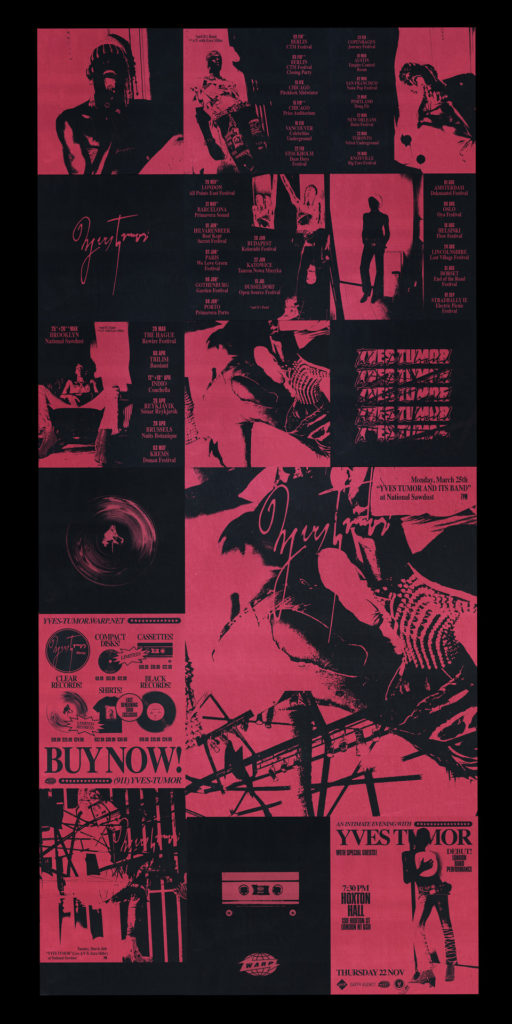

We met a few years ago when he played a warehouse show in Phoenix that I booked with Rabit. He was DJing under a different name at the time and the Yves Tumor PAN record came out a few months after. We’d stayed in touch somewhat since then and he asked me to help with the packaging design for Safe in the Hands of Love last year after the photoshoot had already taken place. I sort of took on more “creative direction” reigns from that point on as we fleshed out the tour graphics, merchandise, social media presence, and everything that exists after the album came out. We’ve been working on a lot of things coming soon that I’m really excited about. Sean (Bowie a.k.a Yves Tumor) calls all the shots but ultimately gives Creative Director Isamaya Ffrench and I the freedom to craft this character into our most fucked version of a pop star we can imagine. Isamaya has a background in beauty and fashion while mine is everything but that, so it’s a collaboration that I think treads a fine line between accessible yet progressive.

What sort of message are you trying to communicate with the Yves Tumor artwork?

It’s a complicated question for Yves Tumor specifically. The brief for that project as a whole artist is constant redefinition. Musically, aesthetically, and even thematically. The internet has a tendency to define musician’s careers and place them into like-categories, whether it be genre or the message, and expect them to cater to that mold. The experimental people see his Ryiuchi Sakamoto association or early PAN stuff and want to witness the next generation of progressive electronic music. Fans who see music as a political tool want to see Yves Tumor become an icon for black, queer, socially-charged art. These boxes all have their aesthetic cues and the goal is to address all of them and yet none of them. If someone sees the Safe in the Hands of Love art and expects a certain genre, I’d hope they’re surprised to hear something wildly opposite to their expectations and hear the music as it is. If a new fan is gained from that interaction with the art, then I’d say the intended message has been received.

Collin, What are the other projects that have really excited you as an artist?

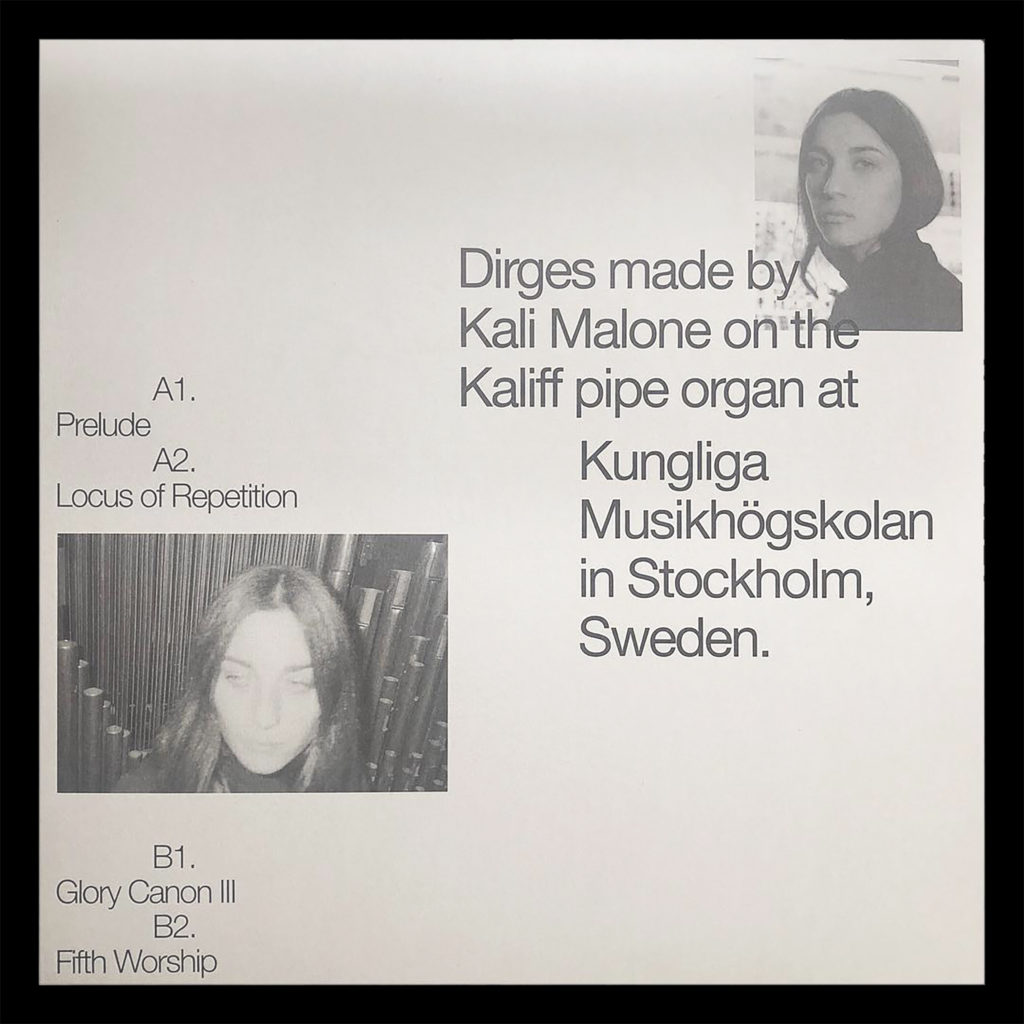

I designed Kali Malone’s Organ Dirges tape on Ascetic House. It was a part of a 12-tape batch, but that record translated to me visually in such a specific way that I felt really satisfied with the outcome of that design. Since then, we did a 12” vinyl version that I think further emphasized the correlation between the typography and layout, and the minimal musical compositions Kali wrote for the record. It’s been really exciting to see how well received that release has been internationally, and extremely satisfying to see Kali bringing her music to more audiences.

And how do you approach work for artists or clients that may not fit your personal aesthetic and style (Zedd, Halsey, etc.)?

In those instances, I tend to be more of a technical production guy rather than a creative influence. My background in typography and layout can be applied to any type of artist or industry. For Zedd, as an example, I work under a creative director, Imogene Strauss, whose ideas are being interpreted and executed through my design abilities. She’ll then work closely with a photographer and/or 3D artists in a similar manner for other aspects of Zedd’s overall identity.

Those bigger budget artists are more about assembling teams with specific abilities rather than relying fully on myself to create every visual element of an artist, like I would with the smaller underground artists. On the other hand, Post Malone is a really exciting artist where the super progressive ideas Travis and Bryan—Post Malone’s art directors and graphic designers—have been pushing through the label have become canon to Post’s identity, and there’s essentially no one telling us the abstract experimentation is wrong. Honestly, I invest a lot of energy into working with Travis and Bryan because it’s one of the only mainstreams artists that is capable of introducing a genuinely experimental visual language to a large audience that is not normally challenged in that way.

What artists and/or designers inspire you both, and why?

CF: John Wiese has always been a major aesthetic and ideological influence to me. His work musically and visually has always maintained this extremely careful balance of understanding its place in culture while innovating within it. His marriage of timeless graphic design principles to the aesthetic opposite extremes of punk processes is hugely impactful to me in terms of design. And the way his solo music, his grindcore band, his fine art, books, and video all tread such contrasting concepts yet all feel uniquely John Wiese is exactly how I would hope others perceive my body of work.

LF: I’ve been following Kevin McCaughey (a.k.a NonPorous/Boot Boyz Biz) for years, and I am deeply influenced by his work. His knowledge of typography and ability to be maximal while also having intelligent layouts and balance is something I have major respect for. His ability to talk about history and topics related to art, music, and design through clothing and small publications is so cool to me.

I’ve also just generally been excited about design that has come out of the Arizona music scene. Arizona H.I.P. Flyers is an archive of hardcore, indie, and punk show flyers that goes back as far as the ‘70s. Collin, Js. Aurelius, and Chase Mason are the AZ real ones as far as it goes with design. Private Selection is Los Angeles-based and always has really sick heavily textured and futuristic designs. I look at a lot of show flyer archives for inspiration, but unfortunately with those a lot of names get disconnected from the designs.

Finally, how did you go about designing the XLR8R+ artwork, and can you explain the idea behind it?

For the design, we decided to collage pictures of our work and ourselves then stylize it in the same way we have stylized photos for HOCO Fest as a reference to both the festival and what we do. Stylistically, this collage represents the physical, punk nature of our work even though it was done completely digitally. From a process standpoint, it represents exactly where we’re at right now in our own practices.