Artist Tips: Silverlining

How to get groove by a master of it.

Artist Tips: Silverlining

How to get groove by a master of it.

Silverlining means different things to different people. For some, the name evokes hazy memories of London’s ‘90s underground, where he performed with some regularity. Ask someone a little bit fresher faced, and he’s one of electronic music’s most prolific producers in the realms of stripped-back house, techno, and electro. Among the leading purveyors of these sounds, his back-catalog sounds as fresh as it did almost three decades ago, and his new material is similarly authentic. Over the last few years, his releases have become staples on dancefloors in Romania, Berlin, Paris, Uruguay, Kiev, Sydney, and beyond. There’s no denying that the Silverlining groove has withstood the test of time.

Asad Rizvi, the man behind the Silverlining alias, was barely 16 years old when he accidentally fell into DJing, having been invited to host an experimental techno show on a London pirate radio station. Around this time, he also began working on his own Warp-inspired electronica, and gave it to Colin Dale who aired it on his seminal Outer Limits show.

Discovery of house and techno affected Rizvi, and his sound shifted somewhat, captured on various releases under various aliases but all produced at a Brixton studio run by Tom Gillieron. His intention was to blend the shuffle-heavy grooves of US house with the abstract energy of Detroit and deep techno, and he adopted the mixing desk and effects as a studio instrument, inspired by the early dub technicians of Jamaica and the disco and early house masters from the US.

Upon committing some of these early studio productions to vinyl in 1995, if only for a short-lived stint of fun, he received booking and release requests from the world over. Outings on Wrong, Eukahouse, and Terry Francis and Nathan Coles’ Wiggle earned Silverlining a cult following in discerning circles, as did collaborations with the likes of Two Right Wrongans, Impossible Beings, and Appleheadz. But as Rizvi’s focus shifted to other genres and tempos towards the mid-’2000s, the Silverlining alias went dormant, causing demand for its record to soar. Some of them still demand over US$200 on Discogs.

Witnessing this, Rizvi relaunched the alias in 2016 through the Silverlining Dubs label, aiming to make his sought-after earlier works more accessible to ordinary vinyl buyers. He also began working on new material, all mixed using a similar approach and with a similar setup as his ‘90s work, and incorporated it onto the reissues. All releases have been mastered to tape for sonic consistency. Track names are omitted on the label’s minimalist artwork, save for remixes of other artists, keeping the focus on the music itself irrespective of their provenance; and they’re all blessed with Silverlining’s utterly addictive groove.

We really welcomed Silverlining to XLR8Rplus with “Kewakagroove,” which draws inspiration from Mood II Swing, “in particular their dubs and the stuff John Ciafone did on his own as Full Swing and Chiapet,” Rizvi explains. In support of the release, available to download here, Rizvi offered some tips on how to get groove in your work.

Editor note: A version of this article appeared in the zine, an accompaniment to the music as part of XLR8R+013, available now.

Let’s start at the beginning.

The word “groove” stems from the Dutch word “groeve,” meaning furrow, ditch, or pit. It’s a linear space that someone or something, fortunately or unfortunately, might find themselves stuck in. We all know that it also came to mean the spiral groove on a rotating phonograph, but the meaning of “a style of playing jazz or similar music, esp. one that is ‘swinging’ or good,” is sourced in the Oxford Dictionary to a Melody Maker journalist in 1932, who wrote of having “such a wonderful time which puts me in a groove.” [sic]

A year later, a Fortune writer commented that some “jazz musicians gave no grandstand performances; they simply got a great burn from playing in the groove.”

These early quotes tell us a lot: the first alludes to a certain form of repetition and hypnosis; and the second indicates an absence of musical dramatics, opting for what also sounds like repetitiveness. This is as relevant today as ever, and still gives a good idea of what groove is. If your track has so many breakdowns that you could comb your hair with the waveform, then it’s unlikely to have groove!

A closely linked concept in the jazz world is “playing in the pocket.” According to this website, the pocket is a “rhythmic glue,” “where a solid rhythm section lives” and a “place of consistency of the kick drum, actually playing the same rhythm, and the bass player linking up and playing to that very same rhythm, or playing off that rhythm.”

This relies on some key elements, such as timing, syncopation, accuracy, and repetition, all of which are also facets of contemporary electronic music. One of the most crucial factors is that the players ensure that they are listening to each other, playing with and not against one another. As an electronic producer, you are the band, so it’s your job to make the little invisible cybernetic stick people in your machines lock together as if they’ve been jamming for years. And don’t let them out of your groeve until they’ve nailed it.

For me, this is characterized with a certain syncopation on a strong, defined rhythm that elicits movement. A fascinating paper on the subject states that “[w]anting to move is reported as the most consistently and robustly defined subjective experience in response to groove,” and, “[a]lthough there are stylistic differences in genres associated with groove, most groove-induced dance is rhythmically periodic and synchronised to the metre.” Furthermore, syncopation is known to produce positive affect in the listener.

Simply put, a successful groove is measured by a human desire to move to the beat, as a result of repetition, with accurately swung timing. Furthermore, a call-and-response, rather than a clash between elements, can create a good groove. More about this later.

The groove that I know and love has evolved through jazz, soul, dub, funk, and disco, among others. These styles of music are characterised by rhythms that can be said to have been played “in the pocket,” and with space between instrumentation that makes each part sound exciting. Some might say slow rock has a groove, or even country and western, but I’m describing what it means to me from my cultural context, which might differ from others. Personally, at a core level, I’ve been most moved by the ‘post-disco’ era between 1979-1984, when disco and funk music were stripped back a bit and experimentation was more pronounced. I could list hundreds of tunes, but here are a few examples of some of the deadliest grooves I know.

I love how each instrument has its own space in this record. There’s so much going on without sounding complicated. This has pure groove for me. One of the finest from this era, in my opinion.

A fast-tempo number by the purple master himself. The groove is centred on a straight beat, with a rhythm based mostly on 8th notes. When the guitar and bass break out of this framework, groove bursts out in no small measure.

And a B-side dub mix from 1983 that’s practically an early house record. Here, there is a call-and-answer between the picked guitar and the synth bass over a pretty straight beat.

“Groove, for me, is like a conversation—or dialectic—between unlikely friends, where musical elements ‘talk’ without interrupting each other. The more time you spend scrutinising this, the more it will become second nature to you.”

Now, here are some tips for finding groove, drawn from my experience.

1. Find your own groove

In order to find your groove, irrespective of the style of electronic music you make, I cannot recommend enough that you go back in time, find your personal bombs—like those I’ve mentioned above—play along to them, tap out their rhythms, dissect them, and figure out what makes them tick. You’ll never sound exactly the same, but if you strive to sound as groovy as those records then you’re on the right track.

Listen not only to the rhythms but also to the notes and how the record is mixed. Pay attention to the spaces in the rhythm, and particularly the “call-and-answer” between contrasting parts, which can be core determinants of groove.

Groove, for me, is like a conversation—or dialectic—between unlikely friends, where musical elements ‘talk’ without interrupting each other. The more time you spend scrutinising this, the more it will become second nature to you. Sit down, twiddle your proverbial beard, and put it all apart, then put it back together as a composite whole. Think of it as homework.

2. First thought best thought

This was the mantra that Beat Generation poet Allen Ginsberg adopted as his mode of writing to ensure that his work was as authentic, naked, and honest as possible.

For me, the first idea that comes to mind is often the best, whether that be a bassline, drum rhythm, or vocal. Whether you have a eureka moment in the middle of the night, and you need to rush into your studio to put it down, or you get that spark in a session, just go with it, and keep writing until you can imagine your track in a place that you’d like it played.

Groove is not something that should be overthought; it should come from the gut. It’s a bit like the phenomenon of the tennis player who can deliver a perfect serve, but when asked to explain how, they fault. While it’s important to understand and appreciate groove, it should come from instinct when writing.

Therefore, I always try to shape my music as quickly as possible. I often start with drums, programming beats, and by paying attention to space. I might then play a bassline that complements those drums. Sometimes I might just start with a bassline and kick, working the top end drums around the bass. It all happens very quickly. In the process, I start to shape the groove, then mix it down, as described below.

If it’s not working, then don’t despair and take a break. There are always more ideas around the corner.

This is a track from 1998 that I did in one hour, while waiting for the tube to open. It’s a DJ tool, with nothing to it other than a simple house groove mixed live on the desk.

3. Sculpt your rhythm section

Traditionally, a rhythm section would consist of drums, percussion, bass, and rhythm guitar. In electronic music, it might also involve percussive synths and stabs. By “sculpting,” I mean finding an overall “shape” of the groove, then chipping away at the details, and mixing.

(i) Drums:

Drums are all about ratio for me. Breaking it down into swing, level, pitch, and mix-down:

Swing—it’s not much of a secret that swing/groove/shuffle quantize is a central component of groove, but it’s not everything. Firstly, you need to determine how much to set it at, if any. Some techno records with no swing can be incredibly groovy, while some tracks with lots of heavy swing can have the opposite effect. Take these two seminal records from the late 1980s, one techno, one house:

There is no swing on these drums at all, yet these tracks are immensely groovy. There’s space between the drums and the snare fills create something similar to a shuffle without actually resorting to it.

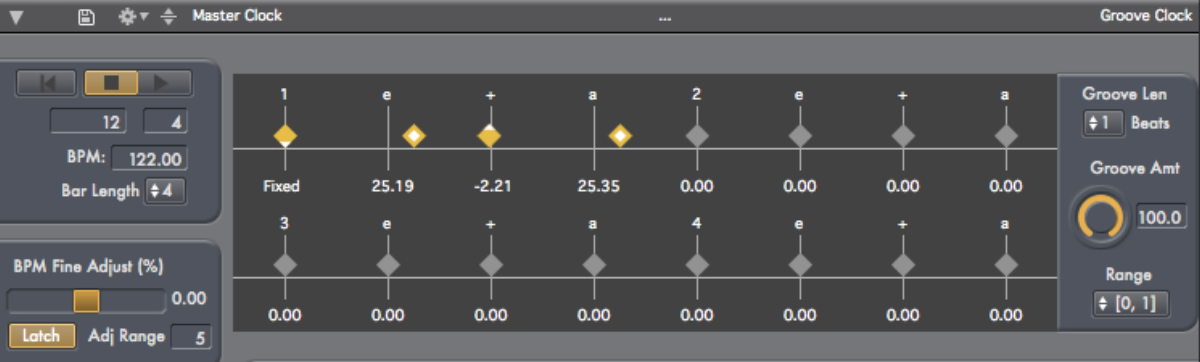

However, I am a sucker for swing. The aforementioned paper found that listeners had a much more favorable response to rhythms where there was an intermediate syncopation of, between 25 and 75 percent, which is about the average swing percentage used in most modern dance music. I personally use Five12’s Numerology for my drum programming. It’s a software model of modular sequencing that allows you to shift your grooves around manually to taste. Most of my friends use Ableton, MPCs, or other boxes that can also do it in different ways. There’s no best tool for this.

For me, the house swing was mastered to perfection by Mood II Swing’s John Ciafone here:

Whatever software you use, experiment with manually shifting your rhythmic sections, such as hats, snares and percussion, backwards and forwards until they all swing the right way for you. If you notice above, I have also made the third 16th of each beat, where the open hat would fall, slightly early. Sometimes, it also sounds good to move the two and four beat, where the snare or clap would normally fall, a little nudge forward or back.

For my drum sounds, I mostly use an Akai S3000XL sampler for its grit and snappiness, as I find it cuts through on systems much more than drums off a computer. Again, gear like analog drum machines, MPCs, Emu SP12s/1200s, and modular gear are a good way to go for your sounds too, if you can.

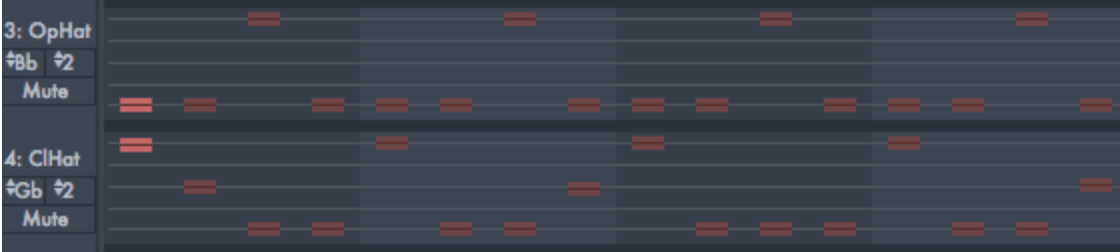

Level—yes the levels of the drums are massively important, even more so than shuffle. Below is a typical, simple house hi-hat pattern:

As you can see, the shuffled hats on the second and fourth 16ths, or semiquavers, of the beats are much quieter than the upbeats. These volume ratios have a profound effect on the groove. This effect can be furthered on the mixer when layering extra drum sounds like hats, snares, and rims, as quiet rhythmic elements of the groove. If you complicate the rhythm like this with more sounds, at different levels, you can build interesting grooves.

Pitch—the pitch of drum hits make a huge difference to how drums “speak.” Try tuning them up or down a bit to key them into the rest of your track, or indeed out.

(ii) Percussion

If you use live or electronic percussion, don’t be afraid to try different grooves to your main drums to loosen things up a bit. Also experiment with different time signatures on some parts so that no two bars loop the same way. In the midst of a tight groove, it can sound really effective to have a part that contrasts it heavily, provided that it doesn’t use up all the space.

(iii) Bass

As I said above, I like my invisible bass player to “play along with” his drummer compadre. Basslines for me need to be warm; they need to be in key, preferably minor or some mode for my taste, but not be overcomplicated with too many musical notes. The spacing should allow room for other instruments. The sound you use and the EQ often make the bassline, and sometimes I like to add a bit of compression to make it sit in the mix, but not too much.

Here are some classic basslines that I love:

Coral Way Chiefs “Release Myself” [Murk Records]

Native Soul ft. Trey Washington “A New Day” (The Black Science Mississippi Black Sunday Remix) [Jus’ Trax]

Tom Gillieron “Piano Band” [Wrong]

Cassio Ware & The Funky People ”I Like You” (Moody Rhodes Soul Dub)[Pan Records]

Occasionally, a central sound, such as a stab, will be bassy enough to do the job of a bassline as it’s best not to complicate it. This was the case on “Groundhog Rave,” posted at the end.

(iv) Rhythmic stabs, synths, or chords

Your rhythmic synths, chords, or guitar will be a huge determinant on the type of track you are doing. Personally, I opt for “less-is-more” in this department if the bass and drums are doing the trick, but this is entirely an aesthetic choice.

(v) Mixdown

I consider this an important part of the groove, too. In all the examples I’ve linked above, the EQ, compression, and overall mix have been central to the track having the right punch. If it sounds like you can grab the sound out of the speakers, then it’s probably mixed well. Just thinking about all this makes me want to drool!

In general, I mix my grooves quite quickly as I want them to sound raw. So I would mix the drums off the Akai and other instruments on the desk and run a live bounce, using mutes, faders, and sends into the Mackie at a high sample rate to not lose any depth. I often use sends to do live “dubs” on sounds and make everything move a bit.

4. Find a central “theme”

A pleasing groove needs some sort of theme. All too often, one hears tracks with lots of sounds going on but there’s nothing that you can pick out and remember. There’s no theme.

This isn’t about obvious hooks or vocals; it’s about a defining focal point. I think all the tracks above have a focal point, but take “Westworld” by John Ciafone (below) for example, that’s classed as techno, but I would say it’s disco in its attitude. There are no melodies, and the drums are very simple, but that white noise riff is the center-point of the groove, in “conversation” with the drums and bass.

But a theme can, of course, be a simple vocal hook, such as in Billy Nightmare “Is This The Life for Me” [Sounds]

Or a dubby guitar, such as in Yellow Sox “Flim Flam” [Nuphonic]

The common denominator is that these elements “jump out” of the groove as a focal point.

To find a theme, a good thing to try is to fit an element to a different part of your loop, that plays off the bassline and drum elements, as a “call-and-answer.” This can be heard in all three of the examples above.

5. Offset the groove with unexpected elements

It can work really well to offset the groove with unexpected elements. This creates an element of surprise that breaks the monotony.

Rhythmic grooves can be found everywhere in daily life. I always recall the scenes in Lars von Trier’s “Dancer in the Dark” where Björk’s character picks up on rhythms from the industrialized world around her. If you’re as weird as me, you might also hear rhythms in everyday stuff around you. So something I am keen on is using something organic or tangible from the real world and turning it into some sort of rhythmic contrast in the track that contributes to the call-and-response of the groove.

A fun thing to do is to record sounds from around the house, or field recordings, cut them up in a sampler, then turn them into quirky rhythmic elements that ‘play’ with each other. You can hear that on “Groundhog Rave” below. It sounds a bit like a groundhog treading on twigs in the woods.

In the Luca Cazal and Ali Black remix below, I went for some sparse, random bleeps, that actually break the groove, but due to their unpredictability, help to emphasise the house groove beneath. That was the intention, anyway.

As I said, everyone’s got their own perception of groove. This is only mine and my methodologies are based on the kind of music I make. Nonetheless, I hope this will be helpful to some people. Here are a few recent productions of mine that might help put all the above into context:

All photos: Kat Green