A Deep Dive Into the Present and History of Romanian House and Techno

Tracks and artist profiles on Amorf, Priku, Sublee, Cosmjn, Dan Andrei, and Orli, as well as an exposé on the inspiring history of electronic music in Romania.

A Deep Dive Into the Present and History of Romanian House and Techno

Tracks and artist profiles on Amorf, Priku, Sublee, Cosmjn, Dan Andrei, and Orli, as well as an exposé on the inspiring history of electronic music in Romania.

Below is the 25th edition of XLR8R+, a very special edition celebrating the house and techno of Romania. The package includes tracks from Amorf, Priku, Sublee, Cosmjn, Dan Andrei, and Orli, as well as artist profiles on all six artists. There’s also a Studio Essentials with Vlad Caia, in which he gives a detailed insight into his favorite machines and how he uses them, and an exposé exploring the history of electronic music in Romania, revealing how the community of artists, including Rhadoo, Raresh, and Petre Inspirescu, formed around Sunrise Booking, the agency at the center of the music scene.

The full edition, including tracks and mixes, can be purchased here. Subscribe to XLR8R+ for exclusive monthly features and packages like this.

Welcome to the 25th edition of XLR8R+.

We’ve written extensively about the deep and trippy minimal music that’s been seeping out of Bucharest, Romania for the better part of a decade. Besides a long-form dig into the scene, we’ve featured a number of the community’s key artists, including Priku, Dan Andrei, Cristi Cons, SIT, and Lizz. We’ve also partnered with Sunwaves Festival to publish sets from the annual event. This month, we’ve decided to revisit Bucharest, releasing six new tracks, plus an exclusive look at an investigative feature that gives an unprecedented insight into what’s a notoriously elusive collective of DJs and producers.

We begin the edition with a track from Amorf, the collaboration of Cristi Cons, Vlad Caia, and pianist Mischa Blanos. “Frames,” recorded exclusively for XLR8R, aims to blend the various genres of music that inspire the group, resulting in a sun-drenched dancefloor cut dripping in melancholia. Up next is Priku with “Outliers,” a deep and dubby cut that perfectly encapsulates his work. Sublee and Cosmjn both deliver their signature groove-led cuts, with the former delivering the low-slung “Little Journey” and the latter “Exor,” a flowing house cut full of acid. Closing the package are Dan Andrei’s “Monite,” a broken-beat synth cut, and Orli, a lesser-known name whose groovy cuts are sprinkled through the sets of the scene’s kingpins. “Rexxar,” his contribution to this edition, rounds things out with sub-bass grooves.

In this edition, we’re publishing an excerpt of William Ralston’s long-form story “Sunrise in Bucharest,” in which the UK writer traces Romania’s minimal music scene from clandestine parties and pirated tapes under the communist dictatorship of Nicolae Ceaușescu to international prestige. It was originally published in print in 2017, but sold out. Digital copies are currently available here.

This segment, which comes towards the end of the original article, reveals how the community of artists, including Rhadoo, Raresh, and Petre Inspirescu, formed around Sunrise Booking, the agency at the center of the music scene. It’s a unique insight into the beginnings of this genre.

There’s also a Studio Essentials feature with Vlad Caia, one-third of Amorf and one half of SIT. Caia gives a detailed insight into his favorite machines and how he uses them. And we’ve included a mix from Orli, specifically recorded for this edition and dropping as an XLR8R Podcast in the next few months.

Artwork is by Amphia’s designer, Claudiu Stefan.

On mastering duties is Kamran Sadeghi.

We hope you enjoy the music.

The XLR8R Team

Click here for the full design experience with the XLR8R+025 Zine.

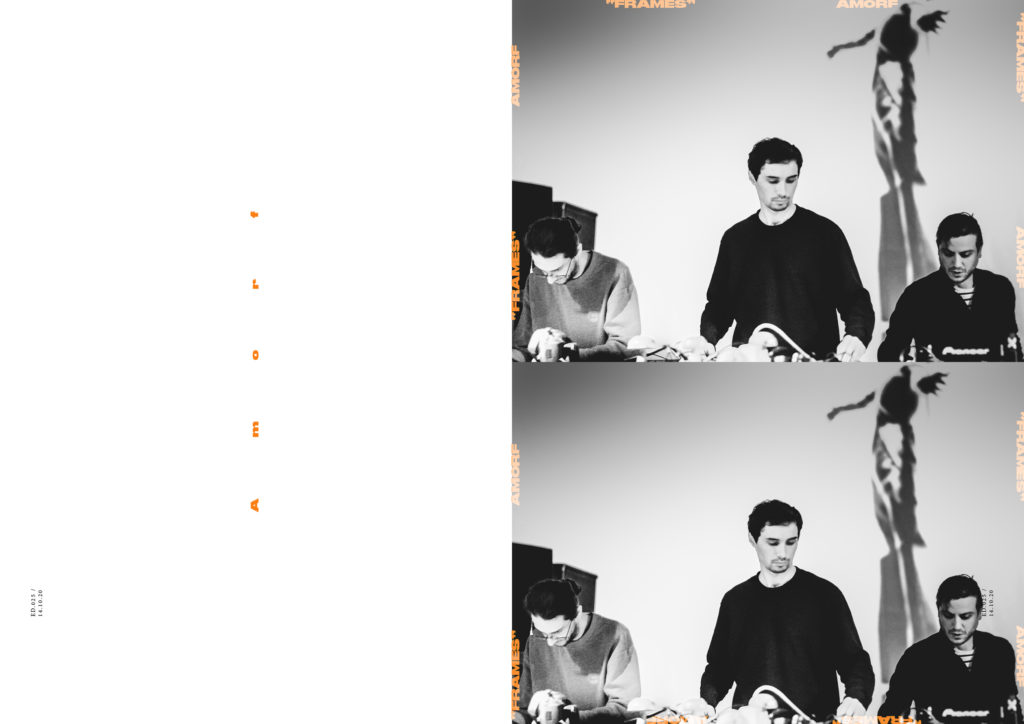

Amorf

Four years have passed since the public first heard Amorf. It was May 2016, meaning Sunwaves, and on stage was Rhadoo. With the sun ushering in a fresh Mamaia morning, the Romanian DJ introduced an uplifting piano track with his signature groove. Youtube videos popped up with clips of the moment, all asking for information. Not even the most loyal fans had the answer. Nobody really knew, apart from Rhadoo himself, and Cristi Cons, Vlad Caia, and Mischa Blanos, the engineers behind this enchanting piece of music.

It wasn’t until the summer of 2017 that anyone else knew who was behind it. In July, the track appeared on an album of the same name, accompanied by five tracks in this distinguishable aesthetic, blending minimal techno rhythms with delicate piano work. It was called “Blending Light” by Amorf, available on Cezar’s Understand label.

Take a look behind the curtain, and you understand why the project sounds like it does. Cristi Cons and Vlad Caia’s collaborative SIT project is one of the few to break out of Bucharest and achieve sustained international success. Mischa Blanos, with Romanian and Russian heritage, makes a living by performing straight piano or mixing it with live sampling to create acoustic-electronic soundscapes. He released his debut album, Indoors, via Infiné last year.

The project’s origins lie at the National University of Music Bucharest, where Cons and Blanos studied. Cons, who has long worked with Caia, brought them together and they joined each other in the studio in January 2016. The goal was to integrate their respective piano backgrounds with electronic music, and this became the blueprint for their first album. The release stemmed from a two-day jam session using an old, out-of-tune upright piano, and plenty of editing. The record sold out almost instantly.

Fast-forward to today, and Amorf is established as one of the most captivating acts in contemporary house and techno. In their more recent material, namely two EPs on Amphia, they’ve replaced Blanos’ piano with more synthesizers, though Blanos is still central. The idea is to achieve non-verbal communication, taking the trio as close to a live band as possible, but with the ability to change their approach in order to pursue whatever direction they choose, Cons explains. In November, Amorf will release Shattered Glass, a new EP to celebrate Amphia’s 20th release.

Recorded especially for XLR8R, “Frames” is the first taste of new material. The track aims to be a blend between different genres of music that inspire the group. The rhythmic Rhodes theme derives from jazz compositions that have influenced them. “When minor chords meet major ones, it gives a sense of instability, similar to our present life when we’re not sure of what may come next,” Mischa Blanos tells XLR8R. “Maybe these musical thoughts recollect some frames from our back-up memory.” The result is pure Amorf: introspective dancefloor bliss.

Studio Essentials: Vlad Caia

Over recent years, I have come to appreciate a more minimalist studio setup. I’ve realized that I work better when I have the bare essentials rather than lots of gear. Using fewer machines to their full potential allows for a more fluid workflow. It also allows for better experimentation, because you’re forced to use each device in ways that go beyond how it’s supposed to be used, and importantly beyond the magic “preset” buttons. By doing this, you begin to develop a sound that’s individual to you, which is important for every artist.

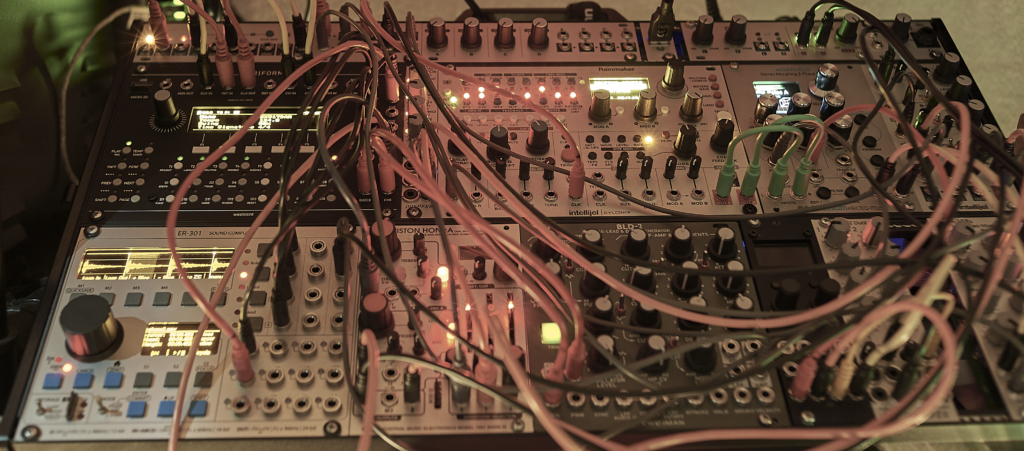

With this in mind, I rely on a hybrid system, which is to say I use both analog and digital instruments, plus three computers that run live effects for manipulation and mangling. These computers have a central role in my studio. Think of them like the beating heart, in that they’re where all the signal paths converge or diverge.

My main computer consists of a server unit housed in the main rack where all the audio/MIDI and digital signals are being received. This unit is used for multi-track recording of live improvised sessions, and it’s also used later for editing and arrangement work. Using the installed patchbays, I can also route audio to different instruments and modules directly from my DAW.

My second computer is a workstation notebook hosted in the instruments rack. I use it mostly for live loop recording and MIDI clips. I also use it to play virtual instruments and run audio effects, much like a guitar pedal. It can do anything I set it up to do, and it’s job is highly dependent on the nature of the track I’m working on.

My third notebook acts as an instrument of sorts and it runs the Max/MSP environment. It’s more like a sketchbook where I try different patches. I synchronize these notebooks using Ableton’s LINK, via wireless to the server unit.

My recordings are all improvised. I program the stuff, so my drums, synths, etc., and then I click “record.” This leaves me with a recording of around 15 to 30 minutes, which I then need to edit. I usually end up doing lots of edits and trying different arrangements of each recording before it becomes a final track. It’s important for me to take time with this. I’ll always test these versions on club systems and take mental notes. With these in mind, I check, re-check, and adjust the things that are obvious or need to be changed, like re-doing gain automation between the kick drum and the bassline, or working some more on EQing the synth lines or maybe taking out some reverb because it’s muddying the mix.

Spending hours on a track can create a bit of a trapped feeling in the auditory sense. It can skew your perception on how it really sounds, and it can also unknowingly move the track in strange directions from an arrangement and mixing point of view. Often these are directions that you didn’t intend for initially. I’ve been countering this by taking a few days off from listening just to clear my mind and have a fresh start. In the meantime, I’ll continue to work on something else entirely or even just play around in the studio. Upon return, I have a different perspective on what works and what I’ve been focusing on way too much.

With this in mind, here are some of the key pieces of gear behind my music.

MicroKorg

I’ll start with the MicroKorg, which is the first synthesizer that I ever bought. I acquired it around 2007 while I was studying in Norway, from a local music shop.

It’s a curious little device with its little keys. It was meant to be just another virtual analog synth, just like any other synth from that era. But it has a sound that’s specific and discernable in my opinion, and that’s what I really like about it. The bass can sound thick or boxy, if you want, and the filter is good enough to make it scream when turning up the resonance. The modulation matrix is quite extensive and has parallels with any modern modular system. It’s also useful if you’re travelling, because it can run on batteries.

I’ve been using this synth in my own projects, with SIT and also in Amorf. A notable use of this synth can be heard doing the bassline duties in a track called “Connection,” released in 2012. It can also be heard doing an arpeggio synth line in a SIT track called “Come Around,” which is included on Sideways LP, Part I, released in 2016 on Amphia Records.

“Come Around” was a fun track to work on, and I had such a blast using the delay effect that’s built into the MicroKorg. The synth creates a dynamic mood, especially while using the resonance on the filter coupled with the delay effect on the end.

You can also hear the synth on Amorf’s “Ouverture” from the album Blending Light released on Understand Live Series in 2017. The synth is present throughout the entire track, playing a repetitive sequence of two notes with the delay effect added. I can’t remember exactly but the oscillator is set to DWGS, which is Korg’s digital waveform generator oscillator type.

To get the most out of the machine, I create my own banks of presets. It’s capable of harsh tones that work great for electronic music, or lush pads that you can use in the background. Did I mention that it also has a Vocoder that’s very usable? Take it a notch further and use the vocoder as an external effect unit patched as an auxiliary send on the mixer. I was surprised when I ran sound through it!

The only downsides are the miniature keybed and the four-voice polyphony. It takes a while to get used to the small keys, and they can be especially tricky when you’re doing fast runs in a live performance. Being able to play just four voices at once takes some planning on the chords you want to hit. Playing elaborated chords one after another can mute previous voices, a nuance that becomes noticeable. You can cheat this by adding some delay and increasing the feedback. Doing it this way it will sustain the previous notes a while longer.

Moog Sub 37

I was excited when news of the Moog Sub 37 started to pop up on discussion boards. Then I saw the NAMM 2014 video with Amos Gaynes and was blown away. This guy really knows how to present a product, and I actually think he’s one of the lead designers of the synth. The synth has many modulation possibilities and many types of arpeggio styles, which is handy for live performances. It also comes with its own sequencer and a beefy filter, as is tradition in the Moog world. I managed to buy one just as it hit the stores around 2015, by doing hourly page refreshes on Thomann.de. I was surprised at how heavy and bulky it was when I received it.

I’ve turned to the Moog Sub 37 a lot over the years. It’s present on every track of Amorf’s Blending Light album, responsible for the bass sequences, resonant percussion sounds, and also the noise swooshes. I also used it across my debut album, Division I, and Division II, particularly on “Cluster” for the bass and synth lines, and “Border Patrol.”

This latter track was a bit more tricky to do because the Sub37 is paraphonic and can’t play more than two notes at the same time because all the oscillators share the same signal path (VCA and VCF), and usually the filter will track only the highest note you hit.

To overcome this issue, for the bassline part, I recorded the same sequence twice with a slight variation of the notes, which meant I ended up with two tracks. I transposed one of the sequences one octave higher to complement the lower one and so it would create a full-bodied bass sound. The synth line comes on top of this foundation as a live improvised sequence.

I think this above example, with “Cluster,” is symbolic of what this machine can do and how it can guide you in terms of setting up modulations. I think it’s a really good bridge between a normal synth and the complicated world of patching a modular. It has CV inputs if you want to interact with it, and one of my favorite features is the audio input connection. I can run external audio signals through its filter. If you modulate the filter in a predictable or random way, it can create lots of surprising rhythmical patterns.

Some drawbacks would be the hefty size of this synth and that fact that you can’t fold the control panel on its back. Even though I’ve built a custom case for air transport, it’s still cumbersome to carry from airport to airport for Amorf’s live shows!

DSI Tempest Analog Drum Machine

I rely heavily on the DSI Tempest for my percussion. It has its own character in regards to the sounds you can come up with, be it percussion or even synths. It’s an instrument that Roger Linn had also worked on, and being an Akai MPC 2000XL enthusiast at that time, it piqued my interest. I did some extensive research on the machine and decided to buy a used one from a friend around 2017.

One thing that still surprises me to this day is the built-in compressor and distortion effects. They’re both analog and can really destroy and mush everything together. This is especially handy as a sound design tool when reaching for those aggressive sounds.

The modulation possibilities are extensive and I often use a random LFO to pan the sounds in a sequence. I achieve lots of movement in the stereo field this way. It also has a peculiar “master” page where I can manipulate the entire collection of sounds I’m using in a sequence. For example, I can stretch the sounds or shorten them by modifying all the release envelopes simultaneously. I can easily create chirpy and glitchy bits with the switch of a button. I can later assign pitch parameters to a ribbon controller on the left side of the instrument and manipulate them on the spot, which is a trick I use during build ups while recording a live session.

Elektron Model:Samples

I’ve had my share of samplers along the years. While I loved the way my AKAI MPC 2000XL sounded, I could never fit it in my setup partly due to the way it was designed. For deeper tweaks to what I’m working on, I would have to stop the unit from playing, ruining the workflow and getting the other instruments out of sync.

What I was looking for was an XoX type of rhythm machine with step programming, so I tried the Electribe ESX-1. It got noisy quickly and I could never achieve that punchy and round sound from the wave files I was loading from the card. It quickly became a popularity contest; the sounds that came with the sampler sounded good and no matter how hard I tried to load my own stuff it could never compete in sound quality.

It was then, in early 2020, that I came across the Elektron Model:Samples, a simple white box sampler with a “what you put in it is what you get” kind of attitude. It does a lot of things right and it’s now become my mainstay percussion and drum machine. I love that I can modulate most of the buttons on its faceplate and that it can loop short pieces of waveforms called Wavetables, which is a bit like the DWGS oscillators on the MicroKorg I mentioned earlier. By sequencing bass or synth lines, I can expand my palette of sounds. Also, because I am a fan of using my own synthesized stuff, I’ve built a collection of modular percussion sounds specifically to be loaded on this drum machine.

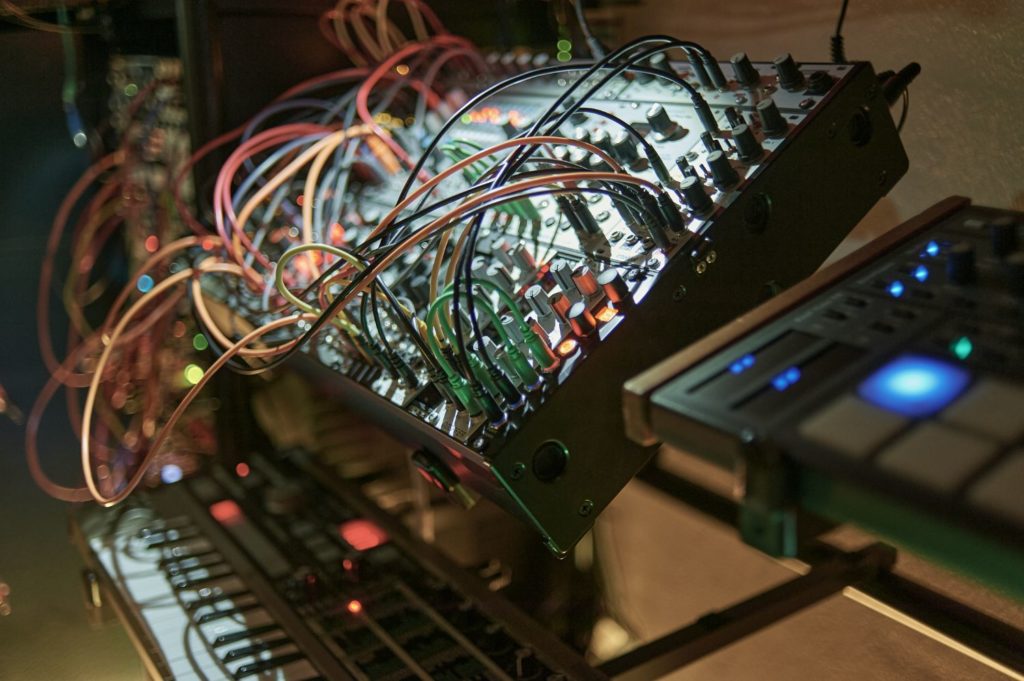

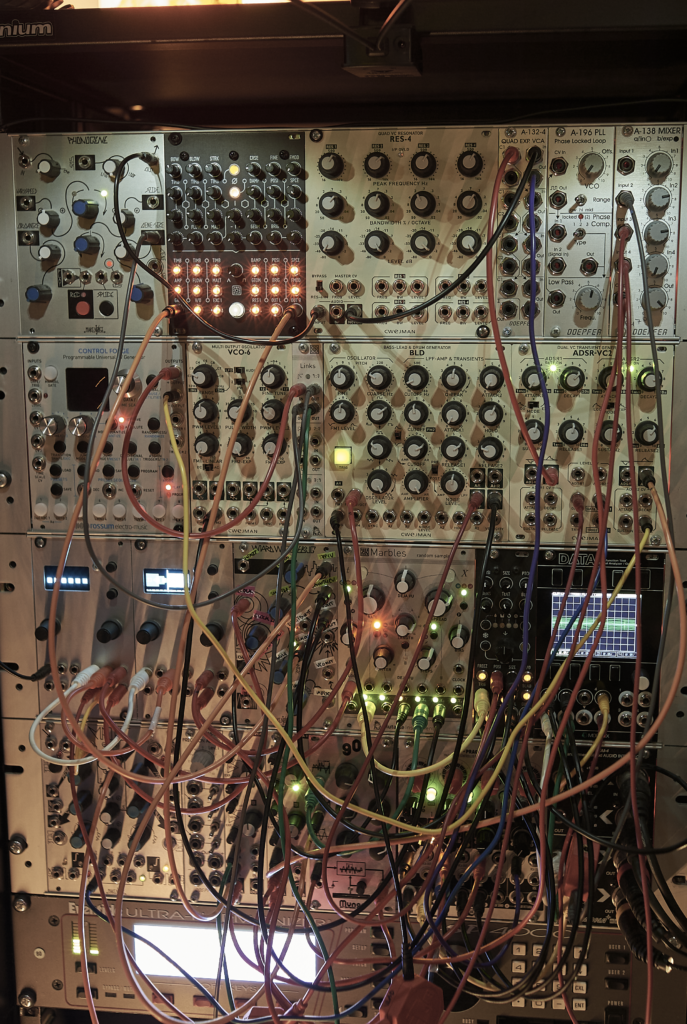

Modular System

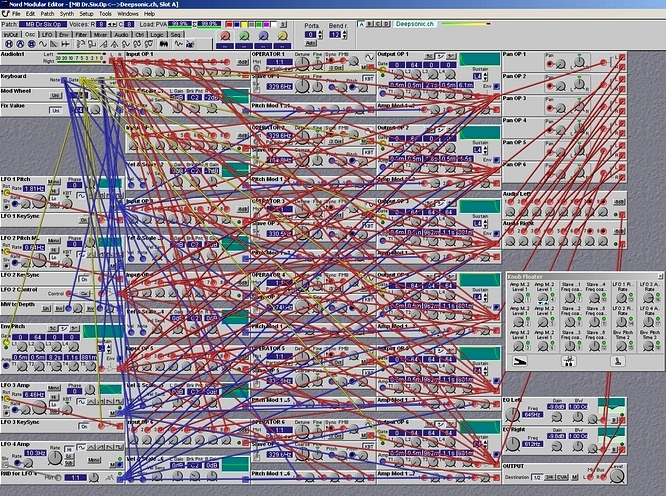

My path to a full modular system started many years ago in software with the introduction of Native Instruments Reaktor. I still remember vividly trying this demo of v2.3 and being so impressed that you could achieve these sounds on a slow, relative to now, computer. I started exploring the way an ensemble is built in this environment and the way these modules were interconnected, much like a real modular system. After some time, as computers became more powerful, these types of software became more accessible and I remember the advent of VAZ Modular and Arturia’s take on Moog Modular (seen in the gallery below).

At this point, the Eurorack was still fresh, and there were far fewer manufacturers than today, so software was much more immediately available. But by 2015 things were moving at a quick pace in the hardware modular world. I actually really wanted to try the Nord Modular G1 first, and so I bought it on eBay. I had scoured forums dedicated to this synthesizer and downloaded around 8,000 patches that I could load onto it. It was an eye-opening experience and had the identical building blocks and modules you could find in a real modular. You had to use its own program to interact with it, but it was unfortunately unstable and would crash badly.

With these new lessons, I set out to build a system that could be flexible to what I need, be it a classical synthesizer architecture with extra modulation and sequencing, an external audio effect with lots of modulation, or for just patching it as a random drone generating source.

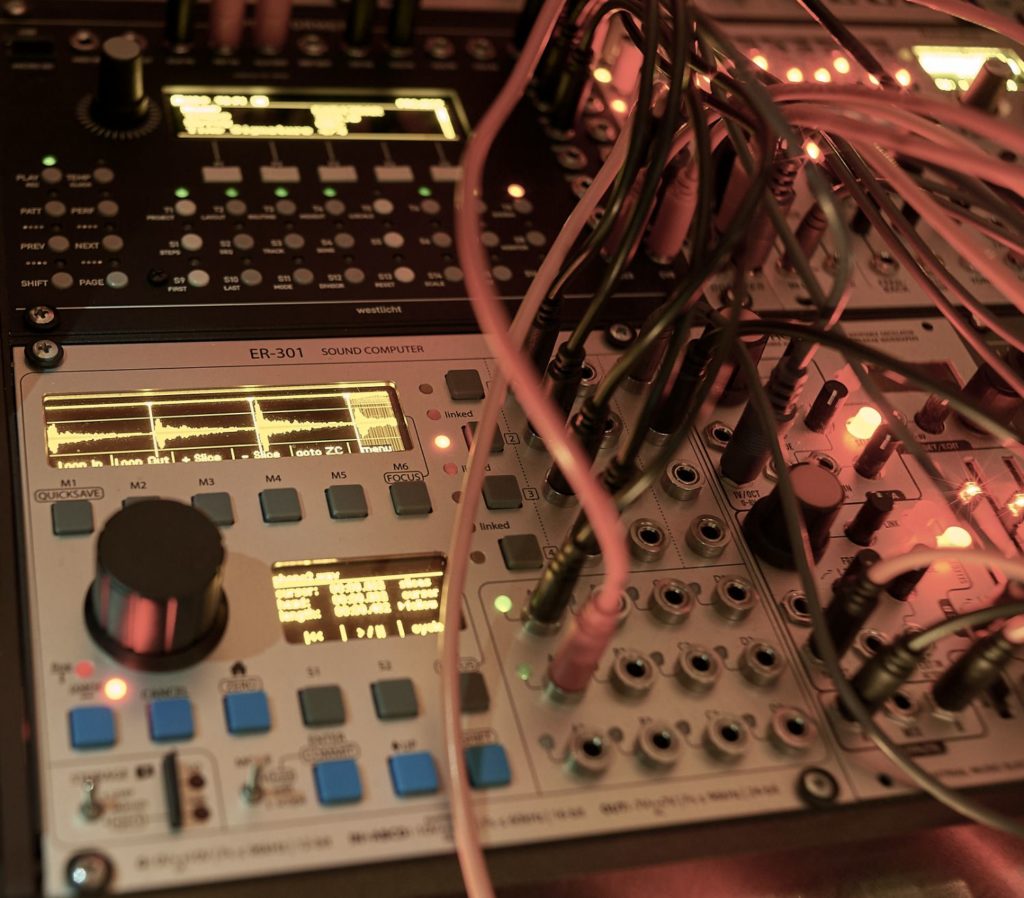

Orthogonal Devices ER-301

My favorite modules that I use often are the Orthogonal Devices ER-301 sound computer. It’s designed to work as a modular inside a modular and I can set it up to any type of job, be it a sampler, oscillator, CV, or audio mixer. There’s an active community around this module and the firmware is constantly worked upon and improved with new features. For now, I use it as a sampler, so I’m triggering different loops and pads to play in sync with other synths. You can hear it doing glitchy drum hats in a recent remix I did for my friends from Alsi, “Scene Hero.” I also have it setup to use as a drum machine, if it’s needed. It’s perfect for travelling as you only need to take a small modular case and you pretty much have everything you need.

Intellijel Rainmaker

Intellijel Rainmaker is another favorite module I use extensively for sound design. I feed audio from my ER-301 sampler and modulate it to create extremely long delay lines by dividing the clock signal. For example, I can divide the 126 BPM by 16 and I end up with delays that change and react once every eight beats. If I change the pitch of these delays I end up with a sort of slow harmonizer effect.

Regarding VCA modules, I’m particularly fond of my Doepfer A-132-4. It’s compact and cheap, and you can change the VCA chips on the back. It has four inputs and two of those have different chips that I’ve installed. The sensitivity of each VCA can be easily trimmed on the back of the module. By adjusting it, you can distort the output volume into distortion territory, which is extremely useful for thick and solid bass sounds.

Make Noise Phonogene

Make Noise Phonogene is a flexible module and I use it as a sample player and for live recording and playback of sequences. It’s my go-to module if I need to use bits of vocals or short bursts of percussion; stuff that is simple and I have to do it fast. I send these sources from my DAW and record it into Phonogene. From then on I patch the module to play this sample in sync or at random times. I’m also experimenting on feeding it the entire output of my modular on set intervals of time. For example, every 32 bars it should record one bar of sequence and play it after 16 bars. After this is done, I can erase the memory and prepare for a new cycle, and so on. By doing this I’m trying to achieve a controlled behavior of the sound that’s being synthesized.

Finding new modules is an intense process, because I have to research exactly what’s needed at that time in my system. As of now, I’m looking for interesting sounding filters, both analog and digital, saturation modules, and utilities like the Expert Sleepers Disting modules, where you have lots of functionality in a small package.

You can hear some of the modules at work in “Expand,” released on Shahr Farang in 2018.

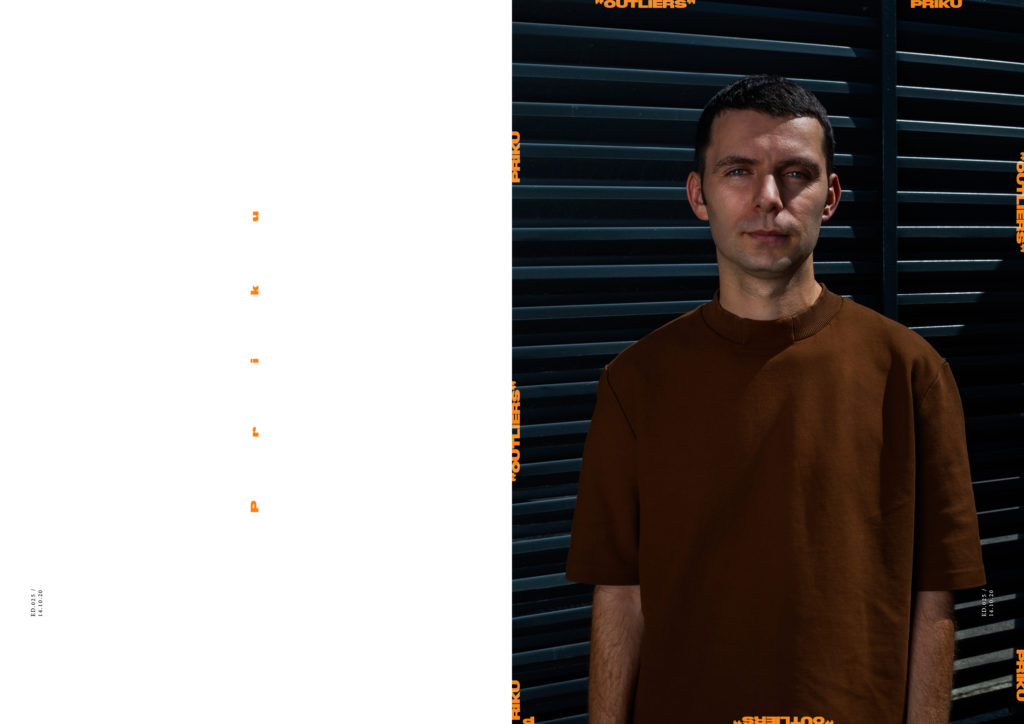

Priku

Priku was XLR8R‘s gateway into the Romanian music scene. Arriving from Amsterdam, the Netherlands after an active few days at ADE, the XLR8R team stumbled its way down to Club EDEN late one evening, excited to see him spin but also in need of rest. It wasn’t until the early hours that we eventually pulled ourselves out, because we were so enchanted with the ethereal music on show. We hadn’t really seen anything like it.

Born and raised in Bucharest, Priku, real name Adrian Niculae, signed to Catalin Ghinea’s Sunrise Booking agency in 2007. He harboured an enthusiasm for technology and music, and he decided to combine these interests by teaching himself to mix records. This was a time when the local minimal music scene was just beginning to bubble. He began performing as Prik, before adopting his Priku alias. While he purveys a slick, minimal sound, he’s also known to lean towards deeper, bassier cuts.

In recent years, Adrian has established himself as one of the most in-demand artists originating from this small Bucharest pocket, and is one of only a handful to have developed a solid audience through Europe and beyond. Catalytic in his success have been key releases on [a:rpia:r], Eastenderz, and his own Motif Records, often under his birth name. He’s achieved this status while maintaining a distinctly low profile, shunning media opportunities except for a few mixes and short interviews. As Atipic, he tours as a live artist.

Adrian’s XLR8R+ contribution is called “Outliers,” and he recorded it in his Bucharest studio over summer. It’s deep and dark, with an irresistible groove—a modern, bassy take on the Romanian sound. It perfectly encapsulates Priku’s work.

Sublee

Bucharest’s Sublee, real name Stefan Nicu, is one of the most prolific producers in the modern Romanian electronic scene. Revolving around a house and techno framework, his sound reaches out past what most would consider Romanian minimal, touching on dub techno, deep house, and atmospheric broken beats, all of which are tied together with his signature low-slung grooves. These inspired takes on the dancefloor have found their way onto labels such as Raresh’s Metereze, where he released a jaw-dropping album of haunting rhythms; DeWalta’s Meander; and Frankfurt-based Rawax, to name just a few.

His sets, too, reach far and wide within the house and techno sphere and are littered with a good helping of his own unreleased productions, lending a surreal and intoxicating edge to his mixing. Like most of his peers in the scene, his sets are transportive affairs that put groove at the center. And while they manage to traverse a wide range, you’ll never hear a track out of place—coherency always reigns supreme.

Sublee’s track for XLR8R+, “Little Journey,” is a nine-minute masterclass in restrained and hypnotic dance music, and a perfect summation of his psychedelic sound.

Cosmjn

Cosmin, real name Cosmin Năstasă, is a young DJ-producer based in Iasi, Romania. Very little is known about him outside his releases and sets, other than the fact that he first connected with electronic music in 2008 and began producing around 2015. Since then, Cosmjn has dropped a head-scratching amount of high-quality vinyl releases on labels like Eastenderz, Subtil, PlayedBy, and Atpic, firmly establishing a foothold in the Romanian scene, with a warm and inviting sound that pulls from acid house, dub, and techno.

For this edition, Cosmjn has delivered one of his acid-soaked rollers. Titled “Exor,” it’s an ethereal, body-moving cut the likes of which would garner numerous “track I.D.” requests in one of the few immaculately crafted mixes of his that have seen the light of day.

Dan Andrei

Dan Andrei is hardly a talker. Even among his media-shy Romanian peers, Andrei is quiet; there’s barely anything about him in the public sphere, barring a mix with XLR8R. All that we know is that he comes from Craiova, just west of Bucharest, and found music through rock, hip-hop, soul, funk, and trip-hop. He signed to the Sunrise agency around 2010, becoming one of the younger artists on the roster. He pushes the eponymous Bucharest sound, with stripped-back, hypnotic grooves, and his lengthy sets can be deeply moving and exhilarating.

And yet within these clost-knit Bucharest circles and beyond, Andrei is a revered name. With his deep and raw selections, he’s become a go-to for Arpiar events, where he plays alongside Raresh, Rhadoo, and Petre Inspirescu. In 2015, he released Parcul Cosmos, an abstract outing that saw him become only the second artist to release a full-length on the respected Arpiar label. Before him was label co-founder Petre Inspirescu. Andrei has since put out music on Be Chosen, Kurbits Records, and Jesus Loved You, and he self-released Vreau Sa Ma Simt Bine, his second album, earlier this year.

Andrei’s track, “Monite,” is a relaxed cut that pairs broken beats with masterful synth work. “Monite” was recorded live in one take and “was based solely on intuition, no thought process was involved,” Andrei explains. “I also remember it fell into place quite quickly; it was all done in about two hours or so. I guess it was one of those fortunate evenings.”

Orli

Of Romanian and Italian descent, Orli, real name Orlando Stefano Tosi, produces and DJs a slick and reduced style of music that pulls from both sides of his heritage—which is to say hypnotizing Italian techno and sleek Romanian minimal. He blends these sounds with those from the ’90s and early 2000s.

Tosi landed on XLR8R’s radar after submitting a selection of tracks via the XLR8R+ submissions portal, but it soon became apparent that his music had been with us for much longer. And this is the case for anyone who follows the stream of Youtube videos that pop up after each edition of Sunwaves Festival in Romania. Listen carefully, and you can hear Tosi’s music across the sets of the scene’s kingpins, including Rhadoo, Vlad Caia, and Cristi Cons. If you’re a fan of minimally-inclined dance music, you’ve almost certainly danced to Orli’s music.

Last year, Tosi launched his own LORI Records with LORI001, a vinyl-only release that included “Ynmwnbnct,” a sought-after track that has been popping up in sets from Rhadoo and Pedro over recent years. A nameless artist EP followed on LORI sub-label IROL, before this year’s TRASMISSIONE DIGITALE, a 15-track digital album inspired by the stories of H.P Lovecraft. The long-player is Tosi’s most accomplished artistic statement, touching on everything from ’80s horror-like broken beat to dark trip-hop and the more surreal grooves he is known for.

Tosi’s XLR8R+ contribution, “Rexxar,” falls into the latter category and showcases his knack for crafting body-moving grooves. He made it this year during lockdown. The track is the type Tosi would keep for personal DJ use; the type he calls “flow” tracks. It revolves around an arp bassline from the Prophet 6, “the focal part of each of my compositions,” Tosi explains. “I hope you like it and that you will find it useful for your sets.”

Claudiu Stefan

Romanian-born multi-disciplinary designer Claudiu Stefan is behind the artwork and visual identity of labels like Amphia, Naural, Ochre, Afterhours., Thinc, and a few more. His aesthetic results from a strong desire for graphic experimentation, a deep passion for electronic music, and his experience as a designer for print. His design for this edition takes his desire for experimentation into new territory, presenting a 3D-rendered object as intricate, detailed, and hallucinogenic as the music it represents.

Editor’s note:

This is an edited and shortened segment of a long-form reportage published by William Ralston in Berlin Quarterly.

In the original edition, Ralston presents the full history behind Romania’s minimal electronic music scene, tracing the genre’s journey from clandestine parties and pirated tapes under the communist dictatorship of Nicolae Ceaușescu to international prestige. Ralston speaks to the seminal artists of the scene, many of whom have never previously given interviews. It was originally published in print in 2017, but sold out. Digital versions have recently been made available via the Berlin Quarterly website.

This segment, which comes towards the end of the original article, reveals how the community of artists, including Rhadoo, Raresh, and Petre Inspirescu, formed around Sunrise Booking, the agency at the center of the music scene.

XLR8R encourages you to support the publisher by buying the full edition here.

___________

1999 — Catalin Ghinea “Tati” and Sunrise

Catalytic in Romania’s electronic music movement has been Catalin Ghinea.

Strada Gheorghe Petrascu lies in eastern Bucharest, and it’s not among the most charming of streets in the capital. The surrounding architecture seems a world away from the beautiful interwar constructions that adorn much of the city’s more central districts. Besides a police station and a large hospital, the area is predominantly residential, with small houses and apartment blocks hugging the roads.

But inside one of these anonymous buildings is a cluttered three-room apartment: the unsuspecting home of Sunrise Booking, the company of Catalin Ghinea. What started as a one-man band, headed up by Ghinea, has evolved into an internationally significant, 11-man operation that sits at the centre of Bucharest’s minimal music scene.

Ghinea himself is a compelling character. He’s tall and athletically built with a strong jawline, though his defining facet is a slick brown ponytail that flirts with his shoulders. A charismatic man with an imposing presence, he exudes confidence. Collaborators, employees, and colleagues in his orbit refer to him as a “Tati,” Romanian for “Daddy.”

Ghinea, and ultimately Sunrise Booking, started with fast-moving consumer goods. Born in 1974, Ghinea graduated from school and married in the early ’90s. Earning only minimal pay as a bartender, he began looking for work to support his family. After floating around in various sales gigs, he took a national marketing position for a growing energy drink brand, which meant spending his days driving between cities within the company distribution network. With a comprehensive black book of Romania’s discotheque owners in his pocket, he added something new to the range of his product portfolio. He was no longer peddling just energy drinks.

The Bucharest electronic music scene was in its infancy, encompassing around 50 people. Ghinea’s presence, as both party-goer and bartender, meant he had contact with all the DJs in the scene—including DJ Raoul, Rosario Internullo, and Rhadoo, who became his first clients. Recognizing their talents, and the demand for music in discotheques, he began promoting them to club owners.

DJs, at this time, worked for clubs as permanent employees, meaning it was the same DJ playing each night. Ghinea wanted to do it differently, so he decided to set up what he calls an “organisation to party.” In 1999, he started Sunrise, the name of which came to him as a joke one morning with a friend on Celentano beach.

The likes of Marco Brigullia and DJ Pagal soon joined the lineup, but Sunrise remained an underground operation: there were no website or advertising; nobody even knew who else Ghinea was working with. “Catalin [Ghinea] would just pick up the phone and call you,” one artist explains. The fees at this point were only modest, around 100 Deutsche Marks or 100 dollars, meaning it remained a labor of love. But the first steps had been taken towards Ghinea’s “dream.” He explains: “I knew I wanted to start a company and run parties with international artists to show to the Romanian public.”

Juggling Sunrise with his day job proved challenging. Monday to Friday was spent on the road, meeting clients, selling product, and persuading venues to host parties with his DJs. At the end of the week he would return to Bucharest, pick up any artists whom he’d managed to book and then get back on the road to deliver them to the discotheques. The quintessential self-starting entrepreneur, he did it all; one city on Friday, another on Saturday. Only on Sunday, after a full weekend of partying, would he return to Bucharest, sleep, and then return to his day job. Between 1996 and 2001, he racked up over one million kilometres.

Ghinea’s roster grew over the ensuing years. A lack of competing agencies allowed him to acquire any Romanian DJ, from the underground figures to more commercial names from the radio. Then, in late 2004, he quit his job and began throwing his own Sunrise events, bringing in names from overseas to play to Romanian crowds for the first time. Preference for supporting act slots was given to Ghinea’s underground names, leaving his more commercial clients disgruntled. In 2007, many of these bigger-name artists left the agency, putting Ghinea and Sunrise in a financially vulnerable position. But this proved to be a necessary step towards a grander vision: Ghinea could focus on the “boys,” a small group of young DJs with an insatiable hunger to spin the best music they could get their hands on.

The Boys and Their Music: A Community Forms

Radu Bogdan Cilinca (a.k.a. Rhadoo) was the first of these boys.

Rhadoo is as elusive a character as they come. Born in Galati in 1975, he was among the first generation of DJs to pop up after the revolution. He began performing at Club A, where he played tapes two nights per week throughout the ’90s. By the early 2000s he had secured his own weekly radio show and was traveling across Romania to play. He is a legendary figure—and is, in many ways, the orchestrator of everything that has developed since. Yet little more is known about him.

Despite his reputation as one of the world’s finest DJs, and a global fascination with the minimal scene he instigated, Rhadoo has not spoken publicly. Recent years have seen him become an enigmatic icon for this group of artists. He simply does not interact with the media, or indeed with much of the outside world.

Ghinea met Rhadoo in 1990 at Club A, in Bucharest. They spent ensuing years partying together and a relationship of mutual respect developed. Rhadoo soon began looking to outsource the business side of his budding DJ career and, recognizing Ghinea’s business acumen, he encouraged Ghinea to start an agency. Ghinea became Rhadoo’s unofficial tour manager, even though neither of them really knew what a tour manager was at the time. But they spent weekends on the road together, driving the country from one city to the next—and it was during these many hours of riffing, rambling, and sharing of ideas that the blueprint of today’s community formed.

Rhadoo’s aspiration was simple: he craved the artistic community that was absent during the early post-communist years in Bucharest. He also recognized that just playing music was not enough, and so he sought to provide a platform for those around him. “In order to achieve a bigger goal, you need to work with someone,” he adds. “We needed a community that shared our values in order to create something bigger.” It’s difficult to fathom what these values are, but it seems that at their basis is a commitment to push underground electronic music.

The objective was to work with people who would not try to raise their heads above everyone else; who would think in terms of what they can do for the community rather than what the community can do for them. “We brought people in who understood this. And we made it clear that although this didn’t directly affect them they would benefit from it if they put their efforts into it,” Rhadoo explains.

Arpiar: Rhadoo, Petre Inspirescu, Raresh

Rareș Ionuț Iliescu (a.k.a. Raresh) and Radu Dumitru Bodiu (a.k.a. Petre Inspirescu/Pedro) were among the first to connect with Rhadoo. Although one of the younger members of this “brotherhood,” Raresh is the most celebrated of all the Romanian DJs, and his encyclopaedic knowledge of music has earned him the nickname “Google.”

Growing up in Romania’s Bacău, a 300 kilometre drive from Bucharest, Raresh first heard electronic music in 1997 via an illegal tape of The Prodigy’s The Fat of the Land. In 1999, aged 15, he began DJing at local discotheque XXL, and in December 2000 became a resident DJ at Zebra, the only real house music club in town. He played every weekend, soon connecting with Rhadoo and Petre Inspirescu, both of whom were regular guests. In 2003, he moved to Bucharest to study Chemical Engineering.

Ghinea had been waiting for Raresh to relocate to the capital, because he hoped to sign him to his agency. Ghinea insisted that all artists on the roster reside in the capital, otherwise creating this community would have been impossible. Raresh dropped out of school in 2006 to join Sunrise and focus on music. With the community in its infancy, Raresh played at all of Ghinea’s events, opening for the main act and then continuing at the after-party. It was the most formative part of his career.

Hailing from Brăila, a small town 200 kilometres from Bucharest, Petre Inspirescu joined in around the same time, having met Rhadoo in 2002 via a residency at the Web Club, a small Bucharest venue. Together, they DJ as RPR (Rhadoo, Pedro, Raresh) and run a label, formed in 2006/7, that is credited with releasing the community’s seminal electronic music productions.

Several other names—including Ali Nasser, Demos, Bogdan Barea (a.k.a Boola), and Gubano—also connected with Rhadoo and Ghinea at the turn of the millennium but left before the Sunrise group solidified.

The Community Grows

Cezar Lazar (a.k.a. El Cezere or Cezar) was next to join in. A soft-spoken but essential member of the family, and one of its oldest, he runs the record label Understand, and Our Own, a distributor and booking agency founded with Rhadoo. Not far behind were Serban Goanta (a.k.a Kozonak/Kozo), Florin Cuntan (a.k.a Praslea), Barac Nicolae (a.k.a. Barac), and Adrian Niculae (a.k.a Prik / Priku)—many of whom left home to join this swelling movement. And it was during these early years in the capital that the foundations of today’s community were laid: those who were there became part of this success; those who didn’t missed out. “We were all trying to make it bigger,” one artist says. “It became our mission.”

Ghinea’s Sunrise agency and the events that surrounded it had become the heart of the community, with more names joining soon. It was a natural process: like-minded artists attracting like-minded artists. Sunrise had evolved into a communal platform in a nation otherwise bereft of musical infrastructure.

A Common Style

By around 2007, Romania was becoming closely associated with one identifiable musical aesthetic. It was firmly rooted in Bucharest, the capital, but now it was eliciting discussion on foreign shores, deemed the “Romanian sound.” Founded on loops and novel sequences of rhythms, the music is subtle and ethereal, laced with delicate intricacies over a minimalist baseline. The tracks are long and hypnotic with no explosive breaks and little melody. There also tends to be only a few elements, hence the term “Ro-minimal.”

Those involved deny any notion of a common style. But one could argue that there is a thread running through their work. The reasons behind this unified sound are explained by various theories. Some point to production; the most common explanation is that at the basis of all early Romanian tracks is a beat occurring in the middle of any two bars of a four-bar loop. Another theory is that the kick drums are mastered before production, lending a distinctive sound. Some go so far as to suggest that multiple artists follow uniform templates for studio setup and production.

Likely, there is no single explanation for this common aesthetic. But this last theory is certainly a contributing factor: in the early days it was a common practice for artists to share basic studio setups.

This uniformity has since been reinforced by the community. As Rhadoo explains: “When music becomes the only currency in a group of people, this happens. We have this community of artists that love music. If you share something with someone and you don’t hear anything back then you get turned off quite quickly. This exchange of information has been fundamental to the community we’ve created.”

Ideas, records, and even specific production techniques are continuously shared within the group, meaning that there are certain “in-house” secrets, all of which contribute to a similar sound aesthetic. Raresh says that this is only natural in a “family of people who cherish the same things.”

The country’s isolation in the 2000s also played a part. Although the communist barriers to the wider world had been broken down, access to music remained difficult. There were no record stores in Romania, meaning that locals had to look elsewhere. Rhadoo and Petre Inspirescu often made trips abroad to shop for records, taking longer than 24-hour train rides to Budapest, Prague, or Istanbul.

The expansion offered by online commerce was slow to change things as well: many websites did not include Romania on their drop-down menus until after it joined the European Union in 2007. And even when they did, payment was complicated. A lack of formal online precautionary measures saw a rise in credit card fraud in Romania, leading many online vendors to preclude sales to the country altogether.

Exposure began to evolve in 2001 with the availability of dialup internet in homes. While it did not cater to streaming, it allowed people to share links to recorded sets and tag artists, labels, and genres within them. There were two leading Romanian platforms for this: understand.ro and nights.ro. The former was set up by Kozonak and his peers and operated as a smaller forum that boasted around 300 promoters, critics, and artists at its peak. It was a meeting point for anyone in Romania to talk and share their thoughts on music. Nights.ro was also a larger resource for finding club nights, but it was not focused on the underground. Some of these artist aliases today—Herodot and Kozonak, for example—were their forum usernames.

It wasn’t until later that these artists had access to a wider musical world. Late 2004 saw the introduction of broadband internet and the implementation of peer-to-peer file-sharing networks. It was a breakthrough moment for the scene: the combination of high-speed internet, poverty, and an entrenched sense of isolation triggered a big download culture. This was the only way for Romania to synchronize with what was happening abroad. Between 2004 and 2006, the Romanian public began to explore a world of new genres, artists, and labels, and DJs critical to the music scene began exchanging their collections with one another.

This shared insularity contributed to a certain uniformity. “We were all blank canvases,” Cezar explains, adding that it created a population of “sponges,” all looking to absorb the newfound musical influences to which they were now exposed. But their respective influences were almost all the same; access to wider music and information had been heavily restricted for so long and within this community was a lot of online and offline music exchanging. Learning to produce music and DJ is something you can do via others, and it just so happened that this community all shared the same education—they attended the same parties and were exposed to the same music. “We all attended the same school,” one artist explains.

The Minimal Connection

The introduction of broadband internet educated the masses to the wave of progressive house music that was sweeping across Europe—and they soon began requesting artists from this realm. Foreign artists like John Digweed, Sasha, Danny Howells, James Lavelle, and Lee Burridge soon became frequent visitors, often playing all night to packed crowds, as the sound of Bucharest began to conform to western notions.

Influenced by these parties, this small community of Romanian DJs began experimenting with styles, playing any music they could get hold of. Praslea was playing hard techno, while Rhadoo was playing a hybrid of techno and breakbeat. Many artists even began experimenting with production, frustrated at the lack of material for their sets. “You could only find a few tracks to play out,” Cezar explains. “We were like five DJs, and we didn’t have any material. Everybody was playing the same 100 tracks.”

But soon the artists began searching for a “new way to express themselves,” with many experimenting with more breakbeat and electro sounds. The answer then came from Petre Inspirescu and Rhadoo via Ibiza.

Ibiza to Bucharest

Petre Inspirescu arrived in Ibiza in 2002 to stay with Stefan Cosma, a friend who had left Bucharest after losing his job at MTV. Looking to make ends meet, Cosma began working as a photographer for Space Ibiza and as a writer. He was well-connected on the island, and found some bookings for Pedro at a bar and at private parties.

Minimal techno was sweeping across the island, which impacted Pedro and Rhadoo. DC10 was still an after-party place of sorts, often filled with Italians on a Monday morning, pushing a minimal sound with “a low tempo and steady groove,” Rhadoo recalls. “There was so much energy in the room from the moment you went in,” adding that this gave the DJs a freedom with the music that they could play. “And there were also not so many elements in the tracks,” he adds. This inspired the duo to begin searching for music in this sound aesthetic, both online and when they were on the road. As Ghinea recalls, this is when the “vinyl cases started to change.”

Residence in Ibiza also gave the artists access to records. The introduction of digital DJing software like Serato and Traktor encouraged many DJs to sell their vinyl records, much to the delight of Pedro and Rhadoo. Many artists sold their collections to Vinyl Club, a record store run by DJ Luc Ringeisen. With demand low for underground vinyl, there were boxes upon boxes of old and unwanted records, many of which found their way into Pedro and Rhadoo’s record bags over the course of the season. “We couldn’t afford to go out, so we just searched for music all day, every day,” Rhadoo recalls.

Minimal Arrives in Bucharest

It didn’t take long for these sounds to reach Bucharest. Each October, Rhadoo and Pedro would return to the capital with bags full of new records focused on “minimal-sounding dub techno,” explains Cezar.

These minimal sounds were only presented in the small after-party scene, but the music resonated within this small community. The Romanian DJs were searching for a more interesting musical direction and a minimal sound ticked all the boxes because it allowed for mixing in a more “attractive” way, Cezar recalls.

The country’s lax licensing laws were also a factor. Parties in Romania could go on for well over 48 hours, provided they do not disturb the public outside. And sonic arcs of this duration don’t lend themselves to explosive moments; rather they give DJs the time to build the narratives up slowly and maintain a steady state of flow. Minimal music was a more suitable soundtrack for these conditions.

There was now a template.

In what was a small yet inspired community of artists, a vanguard of pioneers worked together to find aesthetic solutions to a personal and social demand. It was a formative time for this Bucharest underground movement.

CREDITS

XLR8R+025, Released October 2020.

01. Amorf “Frames”

02. Priku “Outliers”

03. Cosmjn “Exor”

04. Sublee “Little Journey”

05. Dan Andrei “Monite”

06. Orli “Rexxar”

Track 1 written and produced by Cristi Cons, Vlad Caia, and Mischa Blanos.

Track 2 written and produced by Adrian Niculae.

Track 3 written and produced by Cosmjn.

Track 4 written and produced by Sublee.

Track 5 written and produced by Dan Andrei.

Track 6 written and produced by Orlando Tossi.

Tracks 2, 3, 4, and 5 mastered by Kamran Sadeghi.

Track 1 mastered by Cristi Cons.

Track 6 mastered by Orlando Tossi.

Artwork by Claudiu Stefan.

Design by Rhys Carlill.

XLR8R+ October 2020.

Support Independent Media

Music, in-depth features, artist content (sample packs, project files, mix downloads), news, and art, for only $3.99/month.