“People misinterpret the job of music writers, that it’s to somehow ensure the health of the music ecosystem. It’s fucking not.” I’ve just asked Michael Hann, former music editor at The Guardian, about the role of the music media in 2019. “The job of music writers is to offer the most reliable and honest information,” he continues. “And to entertain their readers. That’s more or less where it begins and ends.”

Hann’s answer follows a pretty negative line of questioning from me, born out of what feels like a tough period for music journalism. 2018 was the worst year for journalism layoffs since the recession. Music publications like Drowned in Sound and Red Bull Music Academy have been forced to cut entire sections of content or close completely, following the likes of NME, Groove, i-D, The Word, Blender, and Paste. Some surviving publications, like Pitchfork, have announced that their content will not be free to read for much longer, forced to charge readers due to dwindling revenues.

Others are stripping back their editorial, replacing reviews and news stories with sponsored content, so-called journalism written to the specifications of the corporations paying for it. These necessary partnerships with big brands sometimes mean publications are forced to censor the rest of their output for fear of upsetting their sponsors.

Then there’s every writer’s worry about being canceled on social media, huge PR machines pushing the same artists onto the fronts of magazines, and freelance writers being paid next to nothing, if at all. The result, often, is grey, uninteresting writing that makes you wish you’d never learned to read. And if you somehow produce a compelling, original, honest piece of work, it has a fraction of the impact it once would have done—“as much cultural power as someone walking into a forest and smashing your head repeatedly into a tree trunk,” Hann says

There’s also the argument that today’s music malaise, as it is sometimes perceived (the recent dearth of innovation and radical new sounds), is in some part the fault of the media. Jeff Mills, a founding father of techno and by all accounts a deity in electronic music, recently told Resident Advisor that standards in the scene are now too low, and that “media plays a big part in making the standards too low, because they talk too much about people who haven’t done too much.” He went on to say the media should only cover artists who have “done something special. Then it raises the value of everything, and everyone remains at their level until they do something special.” It all suggests an industry in crisis. We’ll get to what “something special” is, but first: here’s what the bloody hell has been going on.

“…for outlets to publish paid-for mixes and premieres under the guise of supporting that artist’s music is to mislead, and thus to fail, their readers.”

Sam Davies

Before the internet, magazines funded themselves through a combination of sales—the $3 or whatever you would pay for each issue—and advertising, the space on their pages bought by companies marketing themselves to readers. As magazines made websites, vast amounts of their content became free to read, meaning readers had little reason to part with their cash and publications became precariously reliant on advertising. Then Facebook and Google began to dominate the online advertising market: in 2018 they took 56.4% of internet ad revenue between them, predicted to rise to 61% this year. This leaves online publications to fight for what’s left, or look for other ways to fund themselves, such as online subscriptions and donations.

Another option is sponsored content, also known as “advertorial,” “native advertising” (because it looks broadly like any other content on the site), or, horrifically, “spon-con.” Publishers say sponsored content currently accounts for 18% of their overall advertising revenues, expected to rise to 32% by 2020.

In the music media, sponsored content deals often come from PR companies representing artists, labels, and events, who offer money to an outlet in return for coverage of one of their releases, gigs, or—most commonly—festivals. Until recently, that meant display advertising (banners with video, image, and text promoting the event), but thanks to Facebook and Google taking all the ad revenue and the widespread use of ad-blockers, marketers now place more value on editorial coverage. This means a PR company funding festival trips for writers, paying for flights, hotels, VIP passes, and all manner of amenities on arrival. In return, the PRs expect editorial on the event, including news posts, previews, features with the artists (look out for all those mentions of the festival in artist interviews), posts on social media, and a review.

If that review is anything less than glowing—and plenty of festivals are hard to enjoy even with unlimited G&Ts—the publication could face some unpleasant conversations with the PRs. I, for one, like others I’ve spoken to, have received bitter emails in response to reviews (including those published in these pages), informing me that my opinion of x-album/event/whatever can’t possibly be accurate because of y-reason, and as a result I can consider myself unwelcome from reviewing anything associated with z-company in future. So far I’ve been backed up by editors, but not everyone is so lucky.

If a publication depends on a PR firm because of the income they provide through advertising, that firm might threaten to pull all their ad money unless a negative review is taken off-site. Increasingly, writers also have to deal with PRs asking to see reviews before they’re published; with survival dependent on keeping their sponsors happy, many have little choice but to oblige, allowing festivals, labels, artists, or their representatives the final say on a review which is about them.

Clara Suess, owner of Suess Media, a PR agency that has worked with record labels like Columbia, Insanity, Skint, and Champion and artists like Solid Blake, Stanton Warriors, Pris, and Lia Mice, explains that the situation goes beyond festivals. Although she says she has no personal experience of artists and their publicists buying features or reviews, she is “aware that there are places. I’ve had this discussion with other PRs and they’re like: ‘well, if you’re stuck…’.”

Danish techno artist Anastasia Kristensen explains: “I have heard a couple of rumors stating that certain female producers have paid to get their music featured or get a cover of a magazine. I think it usually comes from jealousy. However, I do not have a proof or knowledge of direct payment to anyone. It is very different from paying your press agent to help you pitch and co-ordinate press, which is like any other service out there.”

Suess continues: “More and more titles are starting to charge for premieres and guest mixes,” she says. To be clear: that’s artists, labels, and PR agencies having to pay publications to have their track or DJ mix featured on their site? “Yeah. It’s becoming more and more common, and when I explain to labels about this they’re usually quite shocked,” Suess says. “Often what happens is platforms say ‘we’ve got a certain number of paid spots, a certain number of free spots, and once the free spots are used up, especially for last-minute requests, they say ‘look we do have a slot for that week for a premiere or a guest mix, but…’.” She won’t tell me which publications, but says it usually costs about £20, before adding that fees are rising with certain outlets, while big YouTube channels already charge far more, including one who once asked her for a four-figure sum.

It’s a symptom of the ridiculously tight margins to which cash-strapped media outlets are having to operate as ad revenues continue to fall. Derek Robertson, former editor at recently shut-down online magazine Drowned in Sound, has already come to terms with sponsored content as a necessary evil: “I think the time to be proud about stuff like that is long gone. My opinion is that as long as it’s clear that it’s being sponsored and as long as the sponsor doesn’t turn round and say ‘you can’t say that’, I don’t see a problem with it.”

But for outlets to publish paid-for mixes and premieres under the guise of supporting that artist’s music is to mislead, and thus to fail, their readers. It becomes even more nefarious when the content in question is an interview or—worse—a review, washed with a sheen of positivity under the influence of sponsors. All this distorts the musical landscape, allowing the artists and organizations with the most money to buy critical favor. To fulfill Hann’s definition of reliability and honesty, publications must not be funded by the same people they are critiquing.

“Could a white artist have made Slikback’s Tomo? Could a man have made Jenny Hval’s Blood Bitch? Could a binary-gender musician have made Sophie’s Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides? It’s the music media’s job to not only cover but to find music like this, to uncover the next Oil of Every Pearl by listening to artists from every walk of life and bringing them to wider attention.”

Sam Davies

Yet since Hann started writing, decades ago, reliability and honesty have been joined by another stick with which to beat journalists over the head. Thanks largely to the proliferation of musicians brought on by the democratization of music-making and music-distribution technology—the fact that there are now so many artists—arguments now increasingly center on what, or whom, music journalists should be writing about. In electronic music, for instance, nobody can seem to agree which artists deserve the media’s attention.

First and foremost, surely, the answer is good music: positive critiques either analyzing what makes a popular track so impactful or shouting from the rooftops about a thrilling act that nobody’s heard of. There’s also rubbish music that needs writing about: stuff that’s getting attention but which a critic dislikes and must dismantle to stop the artists responsible, invariably the big ones who are making the most money, from getting away with it. (As yet I haven’t thought of a reason to write about rubbish music that nobody knows about.)

Jeff Mills believes the music media is failing to perform this simple function. I reach out to ask his definition of the “something special” that makes an artist worthy of coverage. “I think the term ‘special’ means when something is being displayed and performed that we’ve rarely or haven’t heard or seen before,” he says over email. He adds: “I do not believe that an artist with millions of social media ‘likes’ falls into such a category.”

The perceived prominence of so-called “Instagram DJs” in music magazines has led some to suggest social media is skewing our perceptions of which artists are making the best music. “I don’t believe social media turns water into wine,” said Radio 1 DJ Pete Tong on a panel at Ibiza Music Summit (IMS) this year. Magazines might argue the same, and that they’re entitled to analyze how music’s biggest Instagram stars have become so popular. But social media’s popularity contest is driven by visual stimuli—nice pictures and funny stories: hitting the follow button on an artist’s Instagram page doesn’t necessarily indicate a fondness for their music. That’s not to say that nobody who follows, say, Varg on Instagram has listened to Nordic Flora series—probably lots of them have—so water into wine it is not. But considering the many followers who are just there for the photos (not to mention the growing trend of celebrities buying fake followers), it’s no stretch to say that social media can make a £5 Echo Falls look like Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Anyone claiming to be a connoisseur—that is, a music critic—must be able to tell the difference.

There aren’t many magazines who would admit to covering an artist based on social media alone. There are, however, other possible motivations for featuring musicians who don’t meet Mills’ “special” criteria. Magazine covers today look markedly different from those of 30 years ago, when the likes of NME and Melody Maker were invariably adorned with images of white, male musicians. Today, nearly everyone I speak to seems to agree that we should be writing about music from ethnic minorities, far-flung scenes, LGBTQ+ artists, and women. The motivation for doing so is less clear, but there are two obvious reasons.

The first is that music needs diversity, and that the diversity of sounds being made is inseparable from the diversity of the people making them. Could a white artist have made Slikback’s Tomo? Could a man have made Jenny Hval’s Blood Bitch? Could a binary-gender musician have made Sophie’s Oil of Every Pearl’s Un-Insides? It’s the music media’s job to not only cover but to find music like this, to uncover the next Oil of Every Pearl by listening to artists from every walk of life and bringing them to wider attention. This might be a leap for some, but it seems like no coincidence that techno, a genre dominated by men for 30 years, is now producing little other than inexpressive, self-absorbed (one might say masculine) records. Perhaps years down the line a less homogenous music industry is more likely to produce wild and exciting new ideas—remember them?

The other approach is to actively cover minorities as a kind of initiative for social change. By pushing minority artists, magazines aim to encourage future generations of non-white producers, gay MCs, and women DJs, for example, to get involved in the scene. On that same IMS panel, DJ and broadcaster Jaguar enthused about the positive impact of seeing women and ethnic minorities, like herself, at the top of the scene, mentioning Honey Dijon, The Black Madonna, and Peggy Gou.

But it sometimes feels as though magazines are choosing to cover minority artists with little consideration for how good their music is, promoting an image of diversity at the expense of genuine critique.

German artist Dana Ruh suggests there are some more cynical motivations at play: “In my opinion, the past two or three years as all the discussion about females in the techno scene came up, I just had the feeling some marketing companies saw their chance,” she says. “They looked for young, good-looking women, started to invest in all channels and then it exploded…I guess at this point these magazines started to be interested.”

Though it might not be clear to their readers, many of the minority artists who feature prominently in today’s magazines also happen to be the ones with the largest public backing—not just social media followings but also sponsorship deals with fashion brands and the financial heft of far-reaching PR machines. Revealingly Suess tells me the majority of interviews with artists she represents come about through her approaching writers, not vice-versa; it’s worrying to think of an industry where journalists, rather than seeking out good music themselves, simply write about the artists who marketers tell them to write about.

Dutch artist Steffi concurs: “I think it’s great to feature women, but that is not through over-promoting female artists that might not even be talented but just because they are female.” She also points out that more needs to be done than magazine coverage alone: “The unbalance between male and female is something that has been there for millions of years and should be looked at on a much bigger scale. It takes years and years to change that and lots of work.”

Employing policies of positive discrimination means music magazines performing a role more like that of a charity, working “to ensure the health of the music ecosystem,” as Hann puts it. Doing so at the expense of honest music critiques, arguing that a musician is breaking new ground just because they’re from a minority background, is to sacrifice our role as journalists. It’s easy enough to find good music from the other side of the world, easier than ever in fact. If writing about it also cultivates a more diverse industry, great. But critics do so through critique, through exploring where an artist’s work sits in the world and analyzing what it says about you if it makes you feel a certain way. Simply promoting artists, placing their image wherever you can, and claiming their music is great just because of who they are, is more the job of a PR.

Which brings us to Mills’ next answer. Responding to a question about the importance of women in techno, Mills replies: “Probably the best, most interesting DJs that are women are those who have been in the scene for more than a few years. If showing this fresh new crop of women in the most prominent spot of a magazine is showing progress, then it seems short-sighted and is probably a sign that the magazine probably never took women DJs seriously in the first place, even in a male-dominated genre like techno. Are any of the highlighted women DJs we see today known as great technical DJs? Programming geniuses perhaps? Are they exceptional musicians? Have any of them unlocked a special knowledge that catapults Electronic Music to a new height….? Or has just ‘looking sexyIf ’ [sic] behind the DJ set become a skill? If so, then a magazine that uses this as the premise to have this person featured on the cover sits in the category of fashion modeling or acting.”

I put these comments to Steffi and Ruh and both broadly agree. But I’m struck by hypocrisy in Mills’ emphasis on catapulting electronic music to new heights while his own image continues to appear on the covers and home pages of numerous magazines. Mills hasn’t taken electronic music anywhere fantastically new in the last, say, 20 years, and neither have Richie Hawtin, Armin van Buuren, Robert Hood, Kevin Saunderson, or Adam Beyer, artists who continue to grace our favorite pages not because of radical recent work, but because of what they did in a now bygone era.

Then who is “special” enough to be on a magazine cover? I ask Mills if he’ll provide an example of a recent techno record he likes. He declines: “I’ve made it a habit to never critique anyone else’s work because I can never really know the true meaning and purpose of it.” He doesn’t seem to know and god knows I don’t either. But maybe therein lies the problem: nobody in electronic music has really done anything “special” in the radical, never-seen-before sense that Mills means, for some years now, at least not to the extent that any sort of consensus approval has formed among the press, or indeed the general public. That many of the electronic artists pushed back then are still featured prominently today is indicative of a genre in stasis. All journalists can do about that stasis is look for exciting sounds elsewhere, investigating music made by members of previously ignored communities and shining a light on stuff that nobody would hear otherwise.

When there’s nobody too good to ignore, someone will complain whoever ends up on the cover. The solution for magazines then is simply to write about the artists they think are best—whether they’re British or Palestinian, gay or straight, big on Instagram or completely anonymous.

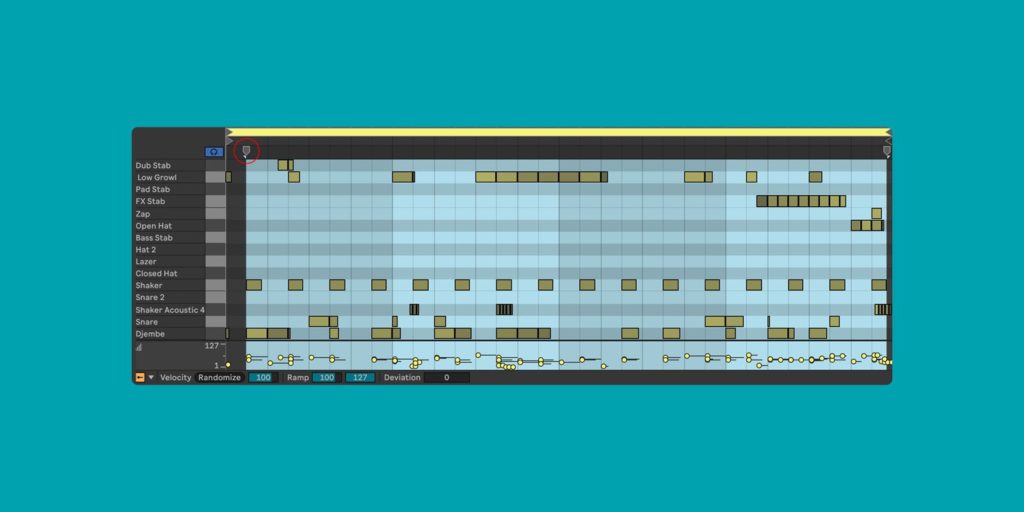

Then there’s the question of how to write about music. Any idiot can say if they like an album or not, but part of a critic’s job is providing expertise on the subject, explaining why it’s good and what the artist is trying to achieve with it. Taking this to its logical conclusion, American pop artist Lizzo reacted to a 6.5/10 review of her recent album with the shouty claim: “PEOPLE WHO ‘REVIEW’ ALBUMS AND DON’T MAKE MUSIC THEMSELVES SHOULD BE UNEMPLOYED.” Mills voices a similar opinion, telling me he’s never read a review that correctly describes how he uses the Roland TR-909 drum machine.

“If a journalist sets out to speak from a position of authority, it should be merely an entry-level requirement that they know their shit top to bottom and inside-out,” says producer and DJ Paul Woolford, though he stops short of Lizzo and Mills: “I think expecting critics to be musicians would mean merely a more performative and possibly more boring style of writing. In some ways, the less analytical they can be, the better. This is purely personal preference, but when you throw away the technical context of what you know about the artist/person, and focus on purely how the music inspires emotion, this can be a greater indicator of the strength of a piece of work.”

There are still critics writing passionately and expertly, often with differing opinions—which is great: we can and should debate about music until we’re blue in the balls. But thanks to social media that debate has ballooned wildly out of control, making the music critic just another voice in a chaotic conversation and dramatically shrinking their impact. Where once a critic could write a bad review without fear of a thousand contrasting opinions coming back at them, now anyone who disagrees with your take on a record can tell you why within a few clicks. And rarely does it stop there.

“I spent a week getting death threats from Lana del Rey fans when I gave her album two out of 10,” says Robertson of his time writing reviews for Drowned in Sound. The most esteemed critics may have Twitter followings in the tens of thousands, but such figures pale in comparison to those of musicians, particularly the megastars. As soon as an artist expresses their displeasure at a negative review, millions of fans feel encouraged pile in, informing the plucky so-and-so who dared to criticize their fave just why they’re wrong, unfit to do their job, and unfit to walk the earth.

Most writers I speak to seem resigned to social media vitriol as part of the job (if you don’t have a thick skin, you’re in the wrong business and so on). And that everyone-has-a-voice, everyone-is-held-accountable vibe comprises not just personal attacks, but also indirect tweets obliquely referencing writers, like a playground brat whispering about you just loud enough that you can hear. It can also mean an artist informing the world that, even though your review was positive, you just didn’t get the album; or a musician sniveling that they weren’t referred to by “their alias,” like a child insisting that everyone calls him Batman. All this, combined with the intimidation tactics of PR firms mentioned above, contributes to a tetchy—at times poisonous—atmosphere surrounding contemporary music criticism.

“The inevitable result is an epidemic of positive reviews, an unstoppable tide of seven- and eight-out-of-10s, a tepid porridge of music writing barely distinguishable from press releases.”

Sam Davies

Music’s biggest players, the global artists and mammoth PR firms, are tightening their grip on the industry narrative. Press days, where an artist is given 10 interview Skype slots with journalists in a few hours, are orchestrated by PRs to create safe, identikit write-ups. Surprise album drops, where music is released with no advance listens for members of the press (or no warning at all), leave reviewers just a few hours to listen before making a judgment, leading most to take the risk-free route of half-hearted positivity. The inevitable result is an epidemic of positive reviews, an unstoppable tide of seven- and eight-out-of-10s, a tepid porridge of music writing barely distinguishable from press releases.

“It does seem like the vehemence and the overall temperature of music writing has gone down,” says Simon Reynolds, author and music journalist of more than 30 years. “People seem to expect critics to not let that kind of “fan” mentality into their writing. They seem to think impersonal judgment is possible or desirable.”

But the subjectivity and personality of music criticism, the simple fact that a review can only ever be one person’s opinion, is crucial to its functionality: without it, a review is not really criticism at all. On the subject of Lizzo’s objection to the personal opinions in that review, Robertson says: “OK, so this person didn’t particularly like what you did or whatever, so what? Fucking grow up.”

There’s something of a paradox in that, while artists and PR teams go to new lengths to control and influence critics, a review’s impact is arguably smaller than ever. “What we think of as the core music press is no longer a monopoly, but an ailing sector within a babble of voices,” says Reynolds. “I think it’s the babble—and the way that means any individual writer’s voice, or magazine’s collective voice, doesn’t have as much influence or impact—that discourages people from making big claims for anything.” But why should being just one voice in a crowded conversation lead writers to dilute their opinions? In some ways this should enable critics to say whatever they want, safe in the knowledge that hardly anyone is reading anyway.

“I think free content ultimately has to die, I think the model is dead. If music journalism becomes accessible through payment only, many will stop reading. But maybe a world where only those willing to pay to read in depth stuff about music is to be desired.”

Derek Robertson

What shines through here is a rose-tinted reverence of the past. Before decrying how bad things are today, it’s worth remembering that yesterday was hardly perfect. Considering how overwhelmingly white and male magazine covers were just 20 years ago, the increased prominence of minority artists now is a sign of progress. Is music journalism in crisis? “In some ways, that question is predicated on the notion of having some kind of golden age of music criticism,” says Hann. “I’m not sure that there ever was.”

But changes are needed. Though “independence” is a tricky term to reconcile in music these days, in the media it remains vital; the sooner publications separate themselves from advertorials and sponsorship deals from those with vested interests in music, the better. That could mean an outlet’s income becomes dependent on charging readers. “I think free content ultimately has to die, I think the model is dead,” says Robertson. “If music journalism becomes accessible through payment only, many will stop reading. But maybe a world where only those willing to pay to read in depth stuff about music is to be desired.”

Some will say this is no longer a realistic goal, that free content is now accepted as standard and for it to remain that way, corporate money is a necessary evil. But also crucial and attainable is the music media’s independence from musicians. Social media—especially Twitter—has eroded the barriers between artist and critic, while in electronic music it seems just about every writer is also a part-time DJ who sometimes messes around on Fruity Loops. Meanwhile, there are plenty of producers who also write reviews themselves. That can lead to friendly relationships, but as New York Times film critic A.O. Scott says: “the tension between artists and critics is crucial.” Paramount to our ability to make reliable and honest critiques is our freedom from the influence of those we are critiquing—which includes artists, labels, festivals, and anyone connected with them.

Also important is our ability to choose our subject matter ourselves, not writing inbox journalism based solely on the stuff we get sent by PRs, but seeking out music of our own accord, searching in places nobody else is looking and writing honestly, reliably, and passionately about why it matters—or why it doesn’t. And remembering that we’re not writing for the artists, for the industry, or even for the listeners. We’re writing for the readers.

Editor note: A previous version of this article accidentally misrepresented a quote from Anastasia Kristensen. This has now been updated.

Photos:

Jeff Mills by Jacob Khrist

Anastasia Kristensen by Morten Bentzon

Steffi by Stephan Redel